Tropical Cathedrals: Elevated architecture in post-war North Queensland

Impressive new cathedrals in North and Far North Queensland were a feature of post-war development. In the 1960s, cathedrals were built in Cairns, Townsville, and Thursday Island. These dioceses were young and still developing but covered vast land areas. Sparsely populated and with limited finances, they struggled to establish themselves. Yet, remarkably, three cathedral projects were realised during the 1960s.

By Lisa Marie Daunt

This is a 20 minute read, published June 2024.

During the nineteenth-century, Australia’s Church of England and Catholic bishops commissioned landmark neo-Gothic stone cathedrals, taking inspiration from those of Great Britain (Andrews, 2001). However, while the dioceses of the country’s southern states had substantially complete cathedrals by World War Two (WWII), this was not so in the northern states, especially in North Queensland. The region’s post-WWII Bishops were disappointed by the inadequate cathedrals of their dioceses and they quickly initiated three cathedral projects. These projects included the completion of St James’ Church of England in Townsville (1956–60), the completion and extension of All Souls’ Quetta Memorial Church of England on Thursday Island (1964–65), and the new St Monica’s Catholic Cathedral in Cairns (1965–68). The Queensland-based architects engaged for these projects were Lund Hutton Newell Black & Paulsen, Reverend John Bayton, and A. Ian Ferrier. These were some of the region’s most prominent ecclesiastical architects and they were eager to rise to the challenges of modern cathedral design (Daunt, 2022, 517). They were also highly cognisant of the need to design for the region’s tropical (hot and humid) climate, as well as its comparatively few skilled tradesmen and limited economic means.

St James Cathedral, Townsville

In 1954, the newly appointed Church of England North Queensland Bishop Ian Shevill arrived in Townsville to an incomplete cathedral — a disappointing ‘half a Cathedral’ (Shevill, 1966, 71). Soon after, he launched a building crusade and a £100,000 War Memorial Appeal Fund for the completion of his cathedral and new permanent churches, under the banner ‘Builders for Christ’. This successful campaign raised £145,000, which enabled many of the diocese’s building projects to be completed during the late1950s and early 1960s. In 1955 he convened the Cathedral Chapter, setting it the task of completing Townsville’s cathedral (Rowland, 1960: 83–84; Shevill, 1966: 68; The Diocese of North Queensland, 1978: 44–57, 16; The Northern Churchman, September 1, 1960: 5).

Though incomplete, Townsville’s ‘half a Cathedral’ could not be considered unremarkable. Indeed, it was the work of one of Australia’s eminent ecclesiastical architectural practices and had been carefully handled. However, its design was restrained due to the diocese’s limited finances — financial support from the state’s other dioceses and others interstate did not amount to much, and assistance from England was even less.

Bishop Stanton’s vision was for a ‘public building of great architectural beauty [to] stimulate the erection of superior buildings in the town’ (The Townsville Herald, 24 December 1887, 66). However, this ambitious vision was challenged. Southerners criticised his plan to even build a cathedral, claiming it was ‘premature’ and a ‘vaulting ambition that o-erleaps itself’ (The Brisbane Courier, 18 July 1885: 4; The Brisbane Courier, 10 August 1885: 6); Townsville, then considered provincial and remote, was disparagingly labelled the ‘end of the world’ (Donegan, 1993: 35).

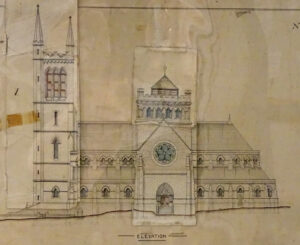

The first stage of the cathedral was designed by Arthur and Cyril Blacket in 1887, continuing the practice of their father, Edmund Thomas Blacket, who was widely recognised as Australia’s main practitioner of ‘correct’ Gothic architecture (Abrahams, 2012: 87–89). The initial schemes were stone (Figure 1) — their preferred cathedral material — and designed to seat 1000. However, to reduce costs, it was significantly redesigned and pared-back to brickwork. The series of redesigns also saw the deletion of the double roof, double walls, the mechanical ventilation system, and the central tower acting as a ventilation shaft proposed in the Blacket brothers initial design to shade and ventilate the building — their ‘highly experimental’ design strategies to keep the cathedral building cool and dry (‘Saint James’ Cathedral,’ 1978; The Queenslander, 18 July 1885: 107; Donegan, 1993: 39–40, 43). Due to limited finances, only part of the cathedral was built, with a temporary porch and a temporary brick wall constructed to secure the cathedral at the transept walls (Figure 2). Initially only a temporary roof was constructed so it could be opened and used for worship in 1892. Without the nave, there was limited cross-ventilation through the transept’s doors. The earlier criticisms from southerners (noted above) — that the cathedral was overambitious, at this time — seemed to ring true. Paying off the debt for the Nineteenth Century works then took decades, further hindered by tropical cyclones (the 2 largest on 26 January 1896 and 9 March 1903), which significantly damaged the cathedral as well many other churches across the diocese. Fortunately, the replacement of the roof structure and cladding in1903 resembled the Blackets’ earlier design and was purportedly ‘aerodynamically safe in the event of another cyclone’ (Donegan, 1993: 43–44).

Figure 2: St James Church of England Cathedral, Townsville (1892, stage 1), by Arthur and Cyril Blacket (www.stjamescathedral.com.au).

In 1956 the Melbourne-based architect Louis Reginald Williams, a known admirer of Edmund Blacket, was commissioned to design stage II of St James’ Cathedral. Williams was then ‘Australia’s most recognised Church of England architect’ and the architect of various inter-war Church of England churches, as well as of alterations and additions to several cathedrals (Moore, 2001: 22, 115–17). The diocesan architects, Ford Hutton Newell Black & Paulsen, a Brisbane and Townsville-based practise, subsequently documented and supervised Williams’ design. Construction started in January 1959 (Donegan, 1993: 87). The completed cathedral was opened for worship on June 12, 1960 (Figure 3).

This Queensland collaboration suited Williams. During the late1930s the Melbourne-trained Peter Edward Newell was Williams’ apprentice. Following Newell’s relocation to Brisbane, Williams referred his Queensland clients to Newell’s practice and recommended them to Shevill for the role of diocesan architects (Moore, 2001: i, 16, 22, 117 and 149; Maidment, 2012: 765; Paulsen 2012). Newell would soon also publish on climatically responsive design for Queensland, and spoke on the need for church design to do so too:

Among all the thousands of churches, not more than a few dozen in Australia have made any attempt to take advantage of present day building techniques to develop a religious architecture in keeping with our times and the climate conditions of their locality. …we must not overlook the climatic considerations affecting the expression of the building as well as its function. (Newell, 1954: 18–19)

Newell’s ideas for modern architecture inclusive of passive climatic design responses are subtly evident in St James’s stage II. The design clearly sought to marry into the earlier stage and limit its modern expression — a design dilemma with which many cathedral architects had grappled with globally.

St James’ stage II extended the cathedral’s nave, took its seating capacity to 769, provided a front façade and entry to the cathedral, as well as a bell tower. On its completion, the The Courier-Mail reported the project’s cost as £66,000 (The Courier-Mail, 13 June 1960, 5). The details of the new nave bays largely replicated the Blacket design. However, various modern elements provide clues to identify the post-war from the Nineteenth Century works: in particular, the lower-level metal louvre windows with their exterior precast-concrete grilles to provide cross-ventilation to the nave and the small differences in the brickwork most evident at the transepts’ exterior re-entrant corners. The front façade and bell tower are also clearly modern architectural statements. Erwin Albert Guth’s sculpture ‘The statue of St James’ is proudly mounted to the left side of this front façade, an important work of modern religious artwork itself. Mosaic tiles shimmer within the entry’s recessed and arched niche.

Figure 4: St James Church of England Cathedral, Townsville, looking from the sanctuary towards the 1960 front entry (Lisa Daunt).

While the cathedral’s interior continued many of the Blacket details with only subtle modern adjustments (Figure 5), the front façade and statue are expressive of more modern architectural and artistic idioms (Figure 4). This approach was strongly supported by Shevill, who prioritised the completion of the cathedral over a slower and more costly build in keeping with the Blacket design. Indeed, Shevill was an advocate for modern architecture and art, expressing on various occasions his desire for Twentieth Century churches for Twentieth Century people (The Northern Churchman, April 1, 1957: 3).

Carpentaria’s All Souls’ Quetta Cathedral, Thursday Island

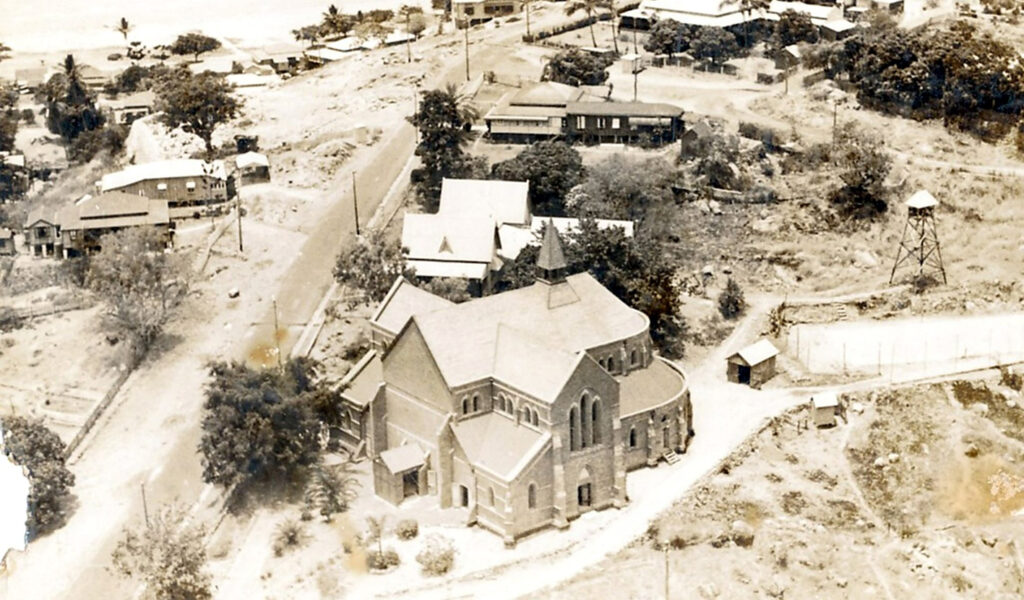

Between 1964 and 1965, Thursday Island’s All Souls’ Quetta Memorial Cathedral — then the Bishop’s seat in the Church of England diocese of Carpentaria — was completed. The first stage was designed by John Hingeston Buckeridge in 1892, built of concrete and rendered to look like sandstone. It was one of Queensland’s earliest concrete ecclesiastical buildings.

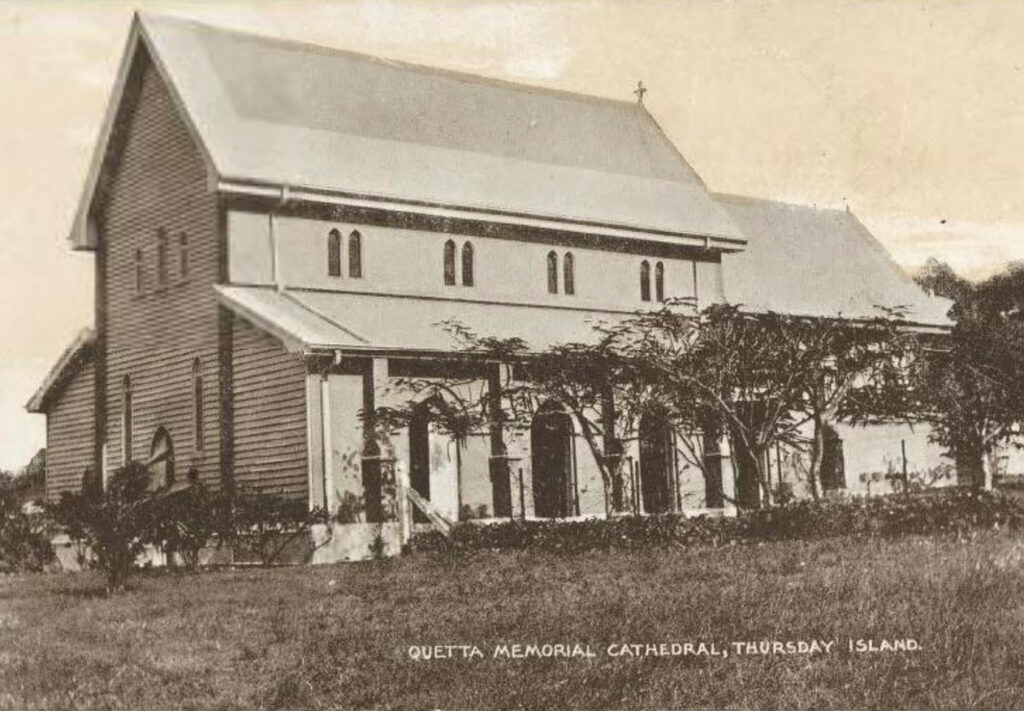

Opened in 1893, the church was soon elevated to a cathedral in 1900 when the first Bishop, Gilbert White, was appointed to the newly formed diocese. Side aisles were temporarily added in timber before 1905 and then, in 1912–15, replaced with permanent side aisles of concrete construction built to the design of Smith Harrington, an architect who was the then Queensland government inspector of works for Thursday Island (Bayton, 1965: 68, 114; Donegan, 1993: 76–77; Watson and McKay, 1984: 99). The side aisles increased the 80–110 seat capacity to 180–210. Harrington’s design included pairs of doors along the sides of the nave within arched openings, to allow cross-ventilation (Figure 6). However, the 1893 timber-clad wall constructed to secure the front of the cathedral remained, awaiting a masonry front fit for a permanent cathedral.

Figure 7: All Souls' Quetta Memorial Cathedral, Thursday Island (1965 extension), designed by Rev. John Bayton (Betty Daly).

There were soon further moves to enhance this remote cathedral’s architecture. Bishop Henry Newton had obtained old stones from ‘some of England’s oldest and greatest cathedral’ during his 1920 visit to England (Donegan, 1993: 90). Over forty years later, on 28 February 1964, one of these old stones, ‘a stone originally placed in Westminster Abbey in the year 1240 was laid at [Quetta] Cathedral to mark the start of the extensions, 64 years after the disaster of the Quetta’ (Bayton, 1965: 109–10; Donegan, 1993: 91). These extensions were completed for Easter 1965 and shortly after the cathedral was renamed The Cathedral Church of All Soul’s and St Bartholomew “Quetta” Memorial.

The mid-1960s stage was designed by Reverend John Bayton, then a Canon and sub‑Dean at the Cathedral. This stage added to the front and side of the cathedral and increased its capacity to 420–50 seats (Figure 8). The project purportedly only cost £4,000 (Bayton, 1965: 111; Donegan, 1993: 91). The extension extended the aisle roofs forward and wrapped them to form a new frontage to the Cathedral, giving a front to the cathedral that had until then been only a simple temporary timber-clad wall. Internal changes were also made at this time in response to international calls for liturgical renewal within the Church of England — as was then occurring across the denominations. The sanctuary space was widened and reordered to extend into the nave. The clergy stalls were moved out of the former sanctuary space, the high altar was positioned forward in the sanctuary, the Bishop’s chair (the cathedra) centred behind the sanctuary, and ambos were positioned either side of the altar.

As an architectural student at Brisbane’s Central Technical College (CTC) and then the University of Queensland (UQ), Bayton worked for Fulton Collin and Associates when it was led by Charles Fulton, who was also the head of school at CTC (Trotter, 2019; Watson, 2012: 264–65). Bayton graduated from the degree course in 1958. Concurrently he pursued his interests in theology and iconography, studying for the priesthood at St Francis Seminary (Milton, Brisbane) and ordained as a Church of England rector in 1957. From 1954 Bayton designed various Queensland churches. His design for the small church of St Luke’s in Kenilworth (1955) was the first in the state to position the altar forward of the liturgical east wall allowing the minister to stand behind it and face the congregation (Bayton, 2019; Daunt, 2020: 72–73; Daunt, 2021: 158, 181–82; Daunt, 2022: 519).

All Souls’ liturgical reordering further develops Bayton’s ideas for modern worship spaces. Responding to emergent liturgical change, he adapted these ideas to suit the small cathedral church. Like Bayton’s prior designs, the mid-1960s extension and alterations of All Souls’ were of modest architectural design in response to its remote tropical island location, nearly non-existent budget, and a local team of volunteers and contractors. Comparatively easy to construct, it used a combination of concrete block and light-weight materials, and incorporated operable louvres for ventilation. Like Bayton’s other designs, artwork was commissioned to complement the project. Stained-glass windows by the Sydney-based artist Stephen Moor (1915–2003) were incorporated above the new entry doors (Daunt, 2021: 524).

Although modern, and liturgically progressive, the project gained little media attention and no mention in the Church’s own Queensland periodical, The Church Chronicle. This was the case, even after both memorial and historical records were restored. More than likely, this was due to the highly critical reception the project seems to have received initially and in subsequent decades. His fellow churchman later wrote: “Bayton made a terrible job on the completion of the Cathedral. He was not an architect” (W.J.A. Daniel’s cited in Palmer, 1985: 16). And one of his successors stated: “we must await the inspired architect (and the funds) who will do just enough demolition, and sensitive modifications and extensions, so that eventually the Cathedral becomes a thing of beauty” (Palmer, 1985: 17). Though recognising the enterprising effort of the project, its low budget and its poor workmanship, it seems they gave little regard to the possibility that Bayton’s design was not realised as he had intended.

A New Catholic Cathedral for Cairns

The first Cairns St Monica’s Catholic church was blessed and opened 10 January 1886, but this timber building was destroyed by a cyclone on 9 February 1927. A new rendered reinforced-concrete two-storey church-school building was opened and blessed in 1927, designed by the Cairns partnership of Lawrence and Lordan (Harry Reginald Lawrence being the likely designer). This second building was elevated to a cathedral on 8 July 1941, when The Vicariate of Queensland (the far-north and Torres Strait Islands) became the diocese of Cairns, though the building was referred to as the pre-cathedral (CCDA, Diocesan History A900 box 6 folder 6). A grander and more substantial design had been prepared by Hennessy, Hennessy, Keesing & Co. in 1926, then the preferred ecclesiastical architects across the state’s Catholic dioceses, especially favoured by Brisbane’s Archbishop James Duhig. But this was abandoned after the cyclone as the most urgent need was to quickly rebuild the school and church buildings.

It was not until the mid-1960s, and several Bishops later, that the ambition to build the cathedral was reinitiated. Taking advantage of government tax deductions for war memorials, Bishop Thomas Vincent Cahill successfully set up the ‘Cairns Catholic War Memorial Cathedral Fund’ in 1964 (CCDA, St Monica’s Cathedral Construction, A300 box 1 folder 1).

Figure 9: St Monica's War Memorial Catholic Cathedral, Cairns (1968), by A. Ian Ferrier, perspective drawing (Ferrier Baudet Archive, courtesy of Catherine Baudet).

The design architect for the new cathedral was Ian Ferrier, who had studied architecture at McGill University in Canada, before migrating to Australia in mid–1953 and arriving in Brisbane in February 1955 (Daunt, 2017: 107). In addition to various churches and chapels, Ferrier had designed St Mary of the Sea Catholic Cathedral in Darwin (1962), which he designed and started the documentation of in 1956–57 while working for the Brisbane practice of J.P. Donoghue, Cusick and Edwards. This led to him acquiring the cathedral commission for his own practise after meeting the Bishop of Cairns in the mid–1960s. Discussions between Bishop Cahill and Ferrier commenced late–1964 and Ferrier produced an initial sketch design in early–1965 (Daunt, 2021: 531; Daunt, 2022: 528). With both Bishop Cahill and Ferrier collaborating for this project, the expectations of their peers were high. For instance, Patrick O’Donnell, the Archbishop of Brisbane, spoke of Bishop Cahill at the twenty-five-year celebration of the Cairns diocese:

His opinions and judgements are valued and sought for in the councils of the Australian Hierarchy. His deep theological insights and his gift of languages proved a most valuable asset to the bishops of Australia during the recent Ecumenical Council. He was our liaison and contact with the hierarchies of Italy, Spain and central Europe. My Lord Bishop, that you have put your hand to the great work of erecting here a Cathedral worthy of the traditions of North Queensland, a monument to the pioneers who laid the foundations of the Church in this now prosperous region, is indeed typical of your zeal, your foresight, your faith in the future of the diocese over which you rule. (Archbishop O’Donnell, August 9, 1966)

During the tender period, The Courier-Mail published a photograph of the model with the caption: ‘The designer, Brisbane architect Mr A. Ian Ferrier has striven to relate contemporary architectural forms with the desired classical atmosphere for the building, which will provide for the requirements of the new liturgical forms’ (The Courier-Mail, July 28, 1966).

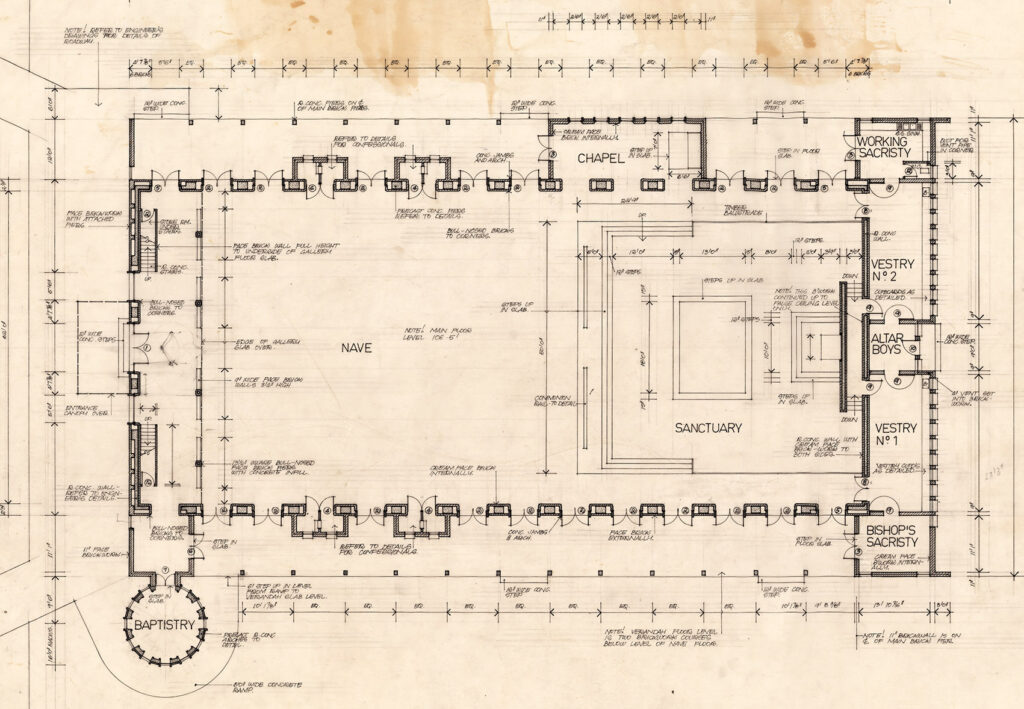

For this design, Ferrier took inspiration from a Canadian Synagogue, Holy Blossom Temple, Toronto (1938), by Jack Brenzel of John B. Perkins associates, and the Unity Chapel of Coventry Cathedral (1961) designed by Basil Spence (Gardiner and Hampson, 1999; Ferrier slide collection). In its final form, the cathedral’s height is equivalent to a four-storey building, with tall pre-cast concrete arched windows containing ruby and amber coloured-glass to the front (mostly now replaced with contemporary glass window art pieces), sides, and baptistry. Red bricks manufactured in Mareeba were used externally contrasting the white concrete details and light cream bricks (from Brisbane) that brighten the interior. The wall behind the cathedra also used light cream brick, to not distract from the altar. The cathedral’s nave was wide and column free. The sanctuary measured approximately 50 ft (15.24 m.) square, taking up the front third of the worship space. This generous sanctuary had an island altar for the Bishop to face the people, with the cathedra on the back wall also facing the people. Ferrier designed the marble altar and the majority of the liturgical furnishings. However, Ferrier’s proposals to commission bespoke artwork were dismissed for cheaper and conservative pieces. The stations of the cross and the wooden crucifix figure were purchased by the diocese from religious importer-suppliers (Daunt, 2022: 528).

In response to Cairns’ tropical climate, verandas ran the length of both sides, with doors off the nave at regular intervals for cross-ventilation — a feature of many of Ferrier’s church designs and also the Darwin Cathedral. The wall to roof junction was vented to realise heat. Combined, these design features enabled the opening up of the cathedral building during hot and wet weather.

In 1999, Ferrier’s reflections on the building were mixed. He lamented the design features deleted due to budget constraints and Bishop Cahill’s traditional preferences for art and architecture (Gardiner and Hampson, 1999). As a basilica-type and with a separate baptistry chapel, St Monica’s does not show the same progressiveness evident in Ferrier’s (smaller) church and chapel designs.

Due to high first tender prices (for the scheme shown in Figure 9), Ferrier’s office redocumented the 600-seat cathedral, without the transepts and with a simpler ceiling construction, amongst other adjustments. In its finished form, the new cathedral still cost nearly $300,000 (Daunt, 2021: 531–44; Daunt, 2022: 528 and 530), with Bishop Cahill personally funding the baptistry chapel as a memorial to his parents (CCDA St Monica’s Cathedral Construction, A300 box 1 folder 2).

St Monica’s foundation stone was laid on 28 May 1967 by Bishop Cahill, with the announcement made that it was to be ‘a War Memorial to the Australian and American Forces who died in the defence of Australia and particularly in the Battle of the Coral Sea.’ On this same occasion the diocese’s status as the only Australian Catholic diocese without a cathedral was emphasised along with the project’s ambitions for the city of Cairns: ‘So the City of Carins will be enhanced not only by the erection of a beautiful building but by becoming a truly Cathedral City’ (J.J. Lander address 28 May 1967, CCDA, St Monica’s Cathedral Construction, A300 box 1 folder 2). St Monica’s was opened and consecrated on 8 July 1968, with the majority of the country’s Archbishops, Bishops, and the Cardinal in attendance, as well as ex-servicemen, many of the city’s leaders and politicians, and a large press contingent from both television and radio.

Figure 12: St Monica's War Memorial Catholic Cathedral, Cairns (1968), by A. Ian Ferrier (Lisa Daunt).

The Cathedral is an evolving piece of architecture. One of the most contentious 1960s design features has been supplanted — the ruby glass windows have been replaced with dramatic bespoke glass artworks created between 1995 and 2018. The Sunshine Coast based glass artists Gerry Cummins and Jill Stephs designed and installed the ‘Peace Windows’ (1995) and then the ‘Creation Windows’ (1998, 1999 and 2000) (Douglas, 2012: 7–9). In 2018 the Baptistery was refurbished and new windows were installed to this space, too. These windows depict a creation narrative of the universe, but with reference to North Queensland. Arguably, the artistry of these windows both competes with and enhances the cathedral’s modern architecture.

Conclusion

These three 1960s North Queensland cathedral projects were achieved with remarkable speed, in part due to their small size and economic constraints — a very different outcome to the modern, highly symbolic, landmark cathedrals built abroad in the post-war period in established dioceses of the Global North.

A priority for the region’s Bishops was ‘completed’ cathedrals, as these young dioceses strove to establish and develop a breath of ecclesiastical infrastructures across their territories. This highly developmentally driven outlook enabled the region’s Bishops to accept realistic, ‘municipal’ scaled, projects that adopted the emergent ideas of modern architecture, as opposed to the expensive and time-consuming ecclesiastical architecture of neo-Gothic designs. Arguably, together with the remarkable number of churches built in the same period, the region’s post-war cathedrals are also emblematic of an ambition different from that of North Queensland’s nineteenth-century Bishops, who aimed to start building worthy cathedrals without necessarily completing them.

These were highly challenging projects, though not for the same reasons as cathedrals of other locations. The projects were very important to their development-driven Bishops, and architecturally challenging. The need to design for the region’s tropical (hot and humid) climate, as well as its comparatively few skilled tradesmen, and disappointingly limited economic means presented significant hurdles. For the architects these were career defining projects, even though they were comparatively small cathedrals. Despite criticisms of their work, and a lack of the same kind of recognition given to larger and earlier designs, they each rose to the challenges of modern cathedral design.

Acknowledgements

This article further develops research previously published as Lisa Marie Daunt, ‘Tradition and Modern Ideas: building post-war cathedrals in Queensland and adjoining territories.’ In David Kroll, James Curry, Madeline Nolan (eds), Ultra: Positions and Polarities Beyond Crisis, Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand: 38. Adelaide: SAHANZ, 2022, 516–31.

Sources and further reading

Abrahams, H. 2012. ‘Blacket, Edmund.’ In P. Goad and J. Willis (eds), The Encyclopedia of Australian Architecture. New York: Cambridge University Press, 87–9.

Allom Lovell Pty Ltd. 1998. ‘St James Cathedral Townsville a Conservation Plan for The Anglican Diocese of North Queensland’

Andrews, B. 2001. Australian Gothic; The Gothic Revival in Australian Architecture from the 1840s to the 1950s. Melbourne: The Miegunyah Press, Melbourne University Press.

‘Archbishop O’Donnell Officiates at Cairns Jubilee Ceremonies.’ 18 August 1966. The Catholic Leader. Queensland.

Bayton, J. 1965. Cross over Carpentaria: being a History of the Church of England in Northern Australia, From 1865–1965. Brisbane: W.R. Smith & Paterson.

Bayton, Bishop J. 13 March 2019. Interviewed by Lisa Marie Daunt, Queensland.

Cairns Catholic Diocese Archives (CCDA). 9 August 1966. ‘Archbishop O’Donnell’s address,’ Silver Jubilee of Diocese. A900 box 6 folder 1.

Cairns Catholic Diocese Archives (CCDA). ‘St Monica’s Cathedral Construction.’ A300 box 1 folders 1 and 2.

Cairns Catholic Diocese Archives (CCDA). ‘Diocesan History.’ A900 box 6 folder 6.

‘Cathedral.’ 1 September 1960. The Northern Churchman. Queensland, 5.

Daunt, L. M. 2021. ‘Communities of faith: Modern church architecture in Queensland, 1945–1977.’ PhD thesis, University of Queensland.

Daunt, L. M. 2020. ‘Communities of Faith: Regional Queensland’s Innovative Modern Post-war Church Architecture.’ In V. Jackson Wyatt, A. Leach and L. Stickells (eds), Distance Looks Back: the 36th Annual Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians. Sydney: SAHANZ, University of Sydney, 65–78.

Daunt, L. M. 2017. ‘Quoting Ian Ferrier (1928–2000): Contributing to Queensland’s post-war modern church architecture.’ In G. Hartoonian and J. Ting (eds), Quotation, Quotation: What Does History Have in Store for Architecture Today? Canberra: SAHANZ, University of Canberra, 101–11.

Daunt, L. M. 2022. ‘Tradition and Modern Ideas: Building Post-war Cathedrals in Queensland and Adjoining Territories.’ In D. Kroll, J. Curry and M. Nolan (eds), Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians. Adelaide: SAHANZ, 516–31.

‘Dedication of the War Memorial church of S. Matthew’s, Mundingburra.’ 1 April 1957. The Northern Churchman. Queensland, 3.

Donegan, G. 1993. ‘“As Hot as Hell” Cathedral Building in Northern Queensland: Gothic Revival Form versus Climate.’ B.Arch thesis, University of Queensland.

Ferrier slide collection. Accessed 2016–2019. Courtesy of Catherine Baudet.

Gardiner, Fiona Joy and Alice L.T.M. Hampson, Interview with Ian Ferrier, St Lucia: 30 May 1999. https://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:452435

‘History of St. James’ Cathedral, Townsville.’ Saint James’ Cathedral Townsville. Accessed 25 September 2022. www.stjamescathedral.com.au/the-cathedral/history/

Maidment, J. 2012. ‘Williams, Louis R.’ In P. Goad and J. Willis (eds), The Encyclopedia of Australian Architecture. New York: Cambridge University Press, 765.

Moore, G. M. 2001. ‘Louis Reginald Williams,’ Vol.1. Masters thesis, University of Melbourne.

Murray, P. and L. Murray. 1998. The Oxford Companion to Christian Art and Architecture. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Newell, P. 1954 (1 January). ‘The Case for Contemporary Church Design,’ Church Chronicle, 17–19.

Palmer, H.E. 1985 (October). ‘Forty Years On: Reminiscences, comments and byways of History.’ Courtesy Anglican North Queensland Diocesan Archives.

Paulsen, B. 12 September 2012. Interview by Don Watson and Janina Gosseye, https://qldarch.net/architect/interview/2561?architectId=132 last accessed 18 May 2021.

‘Proposed Cathedral for North Queensland.’ 18 July 1885. The Queenslander. Queensland, 107.

‘Quetta Memorial Church.’ 2 March 1895. Australian Town and Country Journal. Sydney, 21.

‘Quetta Memorial Precinct.’ Accessed May 29, 2021. Queensland Heritage Register listing 602168.

Rowland, E.C. 1960. The Tropics for Christ: Being a history of the Diocese of North Queensland. Townville: Diocese of North Queensland.

‘Saint James’ Cathedral, a portfolio of drawings photographs and notes on the occasion of the consecration of the cathedral.’ 24 June 1978.

Shevill, I. 1966. Half Time. Brisbane: Jacaranda Press.

‘State News from all over Queensland.’ 28 July 1966. The Courier-Mail.

‘St James Cathedral.’ Accessed 23 September 2022. Queensland Heritage Register listing 600887. https://apps.des.qld.gov.au/heritage-register/detail/?id=600887.

‘St Monica’s War Memorial Cathedral.’ Accessed 1 June 2016. Queensland Heritage Register listing 601961. https://apps.des.qld.gov.au/heritage-register/detail/?id=601961.

‘St. James (N.Q.) opened at last.’ 13 June 1960. The Courier-Mail, 5.

‘The Diocese of North Queensland.’ 1978. Centenary Book, The Diocese of North Queensland, 1878–1978. Townsville.

‘The North Queensland Cathedral.’ 10 August 1885. The Brisbane Courier, 6.

‘The Church of England in Townsville.’ December 1887. The Townsville Herald, 24, 64 and 66.

Trotter, P. and M. Trotter (of Fulton Trotter architects). 20 May 2019. Interviewed by Lisa Marie Daunt.

Watson, D. ‘Fulton, Charles.’ 2012. In P. Goad and J. Willis (eds), The Encyclopedia of Australian Architecture. New York: Cambridge University Press, 264–5.

Watson, D. and J. McKay. 1984. A Directory of Queensland Architects to 1940. St Lucia: Fryer Memorial Library, University of Queensland.

Related articles