The Sunshine Coast's 'Abode of God'

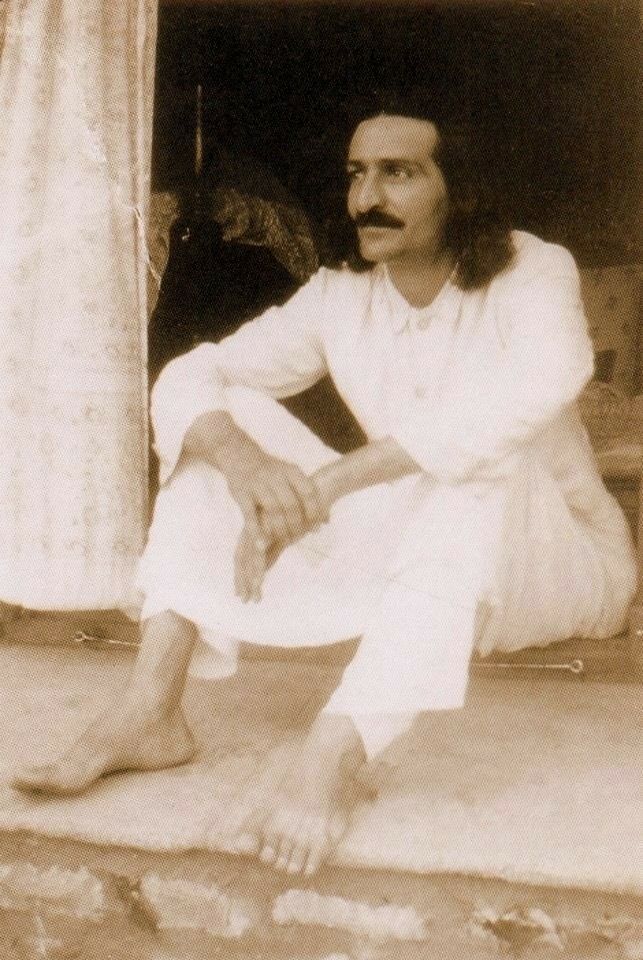

One of the four key sites of a global spiritual movement associated with the Indian figure Meher Baba (1894-1969), Avatar's Abode on Kiels Mountain is today a focus for study, contemplation, and pilgrimage.

By Ray Kerkhove

This is a 20 minute read and nine minute video, published June 2024.

A 15-minute meandering drive through the Maroochydore hinterland brings us to an unexpected sight: a road sign indicating ‘Meher Road’. This seems incongruous in an area long considered part of Queensland’s Bible Belt, ‘Meher’ being an Iranian word (as in Mehrabad International Airport, Tehran). At the end of Meher Road, one encounters ornate gates decorated with the symbols of the world’s major religions. These form the entrance to Avatar’s Abode, a religious centre occupying almost a hundred acres on the summit of Kiels Mountain.

Avatar’s Abode originated with the 1958 visit to Queensland of a Parsi-born Indian spiritual figure known as Avatar Meher Baba (Merwan Irani, 1894–1969). To his followers, Meher Baba (or ‘Compassionate Father’) is God and the latest incarnation of the same personage who was once Krishna, Buddha, Jesus, Muhammad, and other major religious founders. The property is one of four key sites for the global movement that grew around him. It is frequently visited by local followers and others curious about Meher Baba.

Meher Baba stayed at this property for three days in June 1958, naming it Avatar’s Abode and declaring it would one day become a place of world pilgrimage and a true ‘Abode of God’ (Grant, 1987: 95). Ever since, the property has preserved buildings, documents, and items associated with Meher Baba and provides information about him. It is the main venue in Australia for celebrations and programs for his followers, attracting visits from devotees all over the world.

Meher Baba and Baba lovers

The Meher Baba movement has been described as a major ‘underground network’ on account of its subdued and non-proselytising nature, and its emphasis on followers living fully integrated into the habits and culture of the general society rather than seeking visibility. The movement is a loose network of autonomous groups, individuals, and centres that began over a century ago, focused on the personality and teachings of Meher Baba (Kerkhove, 2007: 162f.).

Meher Baba’s writings and sayings – embodied in works such as Discourses, God Speaks, Beams and The Everything and the Nothing – reference Hindu Vedantism, Islamic Sufism, Christian mysticism, Zoroastrianism, and Buddhism. They emphasize selfless service and pure love, especially love for God, love for the Master and the love for the eternal Avatar (‘descent of God’). Meher Baba identified the Avatar as a figure both human and divine, who is repeatedly reborn to revive spirituality and thus has inspired the various religions of the world.

Meher Baba was born in February 1894 in Pune, Maharashtra, into a family of recent Iranian Zoroastrian migrants to a region known for its religious eclecticism (Wagle, 1997: 148f.). He claimed that what he called five ‘Perfect Masters’ from Sufi Muslim and Hindu (Maharastran Datta-cult) lineages brought him into his role as Avatar during his teens and early twenties. These persons he identified as ‘Perfect Masters’ had widespread followings of their own. Between 1914 and 1921, Merwan lived as a close follower of two of them, the Muslim figure Hazrat Babajan and the Hindu figure Upasni Maharaj. In 1921, some of the ‘Five Masters’ made public statements about Meher Baba’s Avatarhood and sent followers to live under his orders.

During the 1920s, Meher Baba and his followers were mostly based at an abandoned army camp outside of Ahmednagar, which became known as ‘Meherabad’. Here he organized devotional programs honouring his Masters, and a range of services for the impoverished region, including lodgings for travelers, a home for lepers, a hospital, a dispensary, and schools. It was during this time, in 1925, that Baba began observing his characteristic silence, which he maintained for the rest of his life. He adopted this practice, communicating to others through signs and an alphabet board, because he believed that ‘things that are real, are given and received in silence.’ He taught that the world had been given enough words, and that it was now time to live them.

Between 1931 and 1937, Meher Baba travelled to Europe, North America and parts of the Middle East and Far East. This attracted much interest from Western media, celebrities, and political figures such as Mahatma Gandhi (Kalchuri, 2001: 1646f.; Anzar, 1974: 32).

However, on returning to India, Meher Baba’s public presence was much reduced, as he increasingly started journeying incognito around the Indian sub-continent to locate and assist ‘spiritual seekers’ and people in need. He was especially interested in what Sufi Muslims called masti, or majzub (Eaton, 1978: 276). These were mostly homeless, seemingly deranged persons who were seen to possess spiritual insight. Meher Baba established some of the first institutes for their care, personally washing and feeding many hundreds. The Wayfarers, a record of this work compiled by British physician Dr William Donkin and published in 1949, was the first detailed analysis of the masti phenomenon (Ernst, 1997: 115).

Meher Baba’s Indian journeys culminated in what he called his ‘New Life’ (1949–52). In this phase, he shut down and gave away all establishments and possessions associated with his name and wandered the Indian subcontinent, relying solely on begging. In the years that followed, he instituted what he called the ‘Free Life’, wherein he lived in partial seclusion, mostly at a village compound (Meherazad, outside Ahmednagar) with a small group of close followers. It was during this period that he produced most of his books and undertook public tours and gatherings in parts of India, in contrast to his usually private and incognito travels of earlier years. He also made more trips to the West, visiting centres devotees had established.

For the last decade of his life, Meher Baba deepened his withdrawal into what he termed the ‘Long Seclusion.’ He ceased public gatherings and public ‘talks’ and could not be visited or contacted. Nevertheless, this period saw Meher Baba become very popular in the West, as his writings and sayings started to circulate there. His books were influential in introducing many Western youth to concepts such as universal love, the importance of the Guru, God-realization, and the irrelevancy of rites.

In the mid-1960s, three young American hippies managed to contact Baba at the Meherazad compound. Baba warned them that the ‘intellectual potential’ of the student world would be lost if drug use continued the way it was at that time. He asked them to encourage other young people to quit narcotics. The three young men thereafter traveled around the world, often hitchhiking, and spoke on major media outlets, debating against drug use. This anti-drug crusade had varying effects (Robbins 1969: 308f.), but it brought Meher Baba further into public awareness. His views on drugs entered academic debates, and posters, cards and buttons with Meher Baba’s image and sayings became a common feature at Western youth events, including the celebrated Woodstock music festival in August 1969. Many young people consequently became attracted to his teachings, most notably the rock musicians Pete Townshend of The Who, Ronnie Lane of The Faces, ‘Melanie’ Safka, and songwriter Billy Nichols.

There has never been a formal structure associated with Meher Baba’s following. Consequently, numbers today are difficult to assess. Baba lovers are estimated at anything from 300,000 people to millions. By far the largest majority reside in India, but there are also tens of thousands of Baba lovers in the US and smaller groups in many countries around the world.

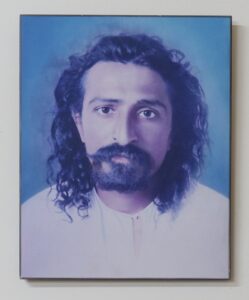

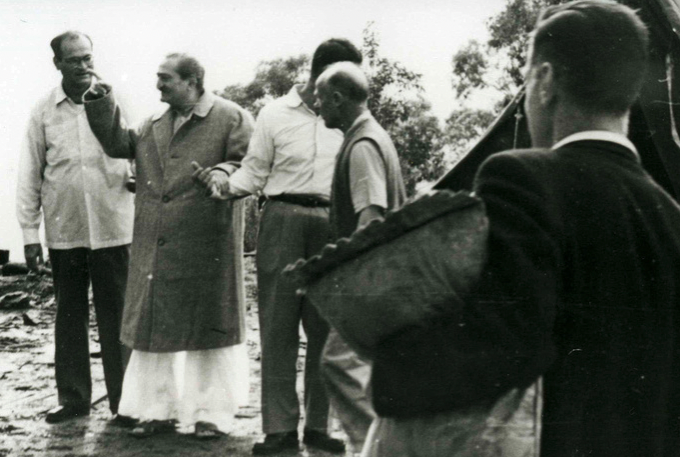

Figure 4: Meher Baba near the men's tents, Avatar's Abode June 1958 (Colin Adams photographer; Avatar's Abode Trust).

Australian Baba lovers

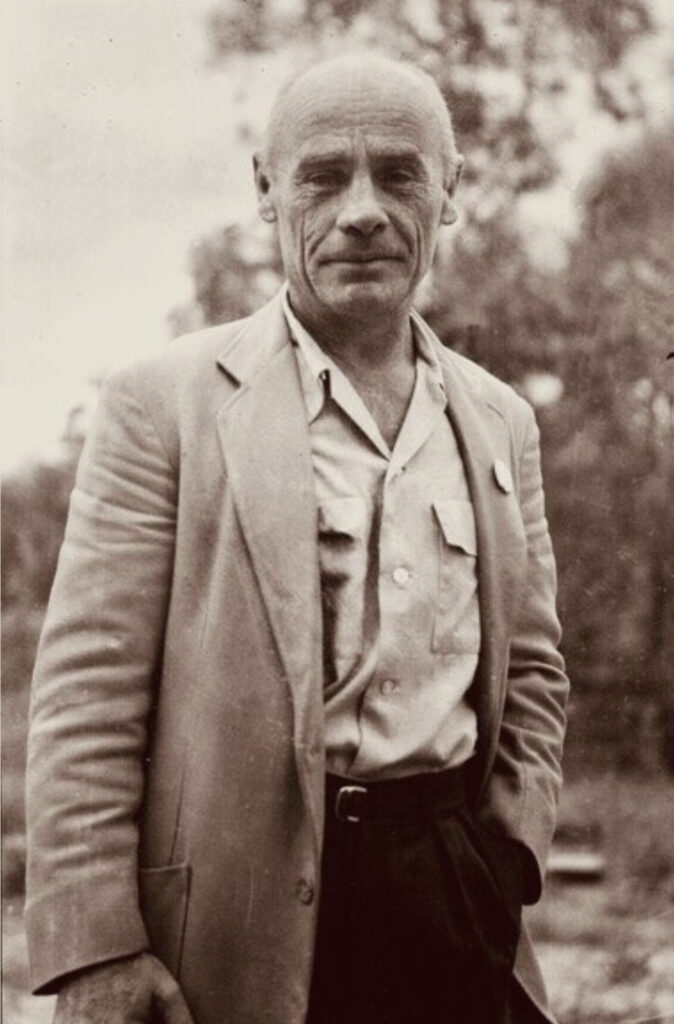

Meher Baba’s Australian following originated in the 1930s, when a few Australians — mostly students of the Cecchetti International School of classical ballet — met Meher Baba overseas and distributed information in Melbourne about him. In the mid-1940s, the American Sufi leader Rabia Martin became convinced that Meher Baba was an important spiritual identity and directed her groups around the world to study his writings. This resulted in Australia’s first Western Sufi groups including Meher Baba’s teachings at their Melbourne, Sydney and Camden meetings, under the instruction of their ‘Sheikh’ or leader, the German-born aristocrat Baron Friedrich von Frankenberg.

When Frankenberg died in 1950, Francis Brabazon succeeded him as Sheikh. Brabazon was a notable bohemian figure, an early Australian Modernist poet and Primitivist artist — part of Melbourne’s Angry Penguins circle (Keating, 2002: 45f.). In 1952, Brabazon went to the USA to meet and assess Meher Baba. He was so impressed that after returning to Australia, he dissolved the Sufi group and declared himself a devotee of Meher Baba. A portion of the Sufi students followed him to become Baba lovers. By 1954, this first Australian ‘Baba group’ had built Meher House at Beacon Hill, Sydney, which Meher Baba visited in 1956. Meher House remains an important centre for Baba lovers today.

In 1958, Queensland was chosen as a more comfortable destination for Meher Baba’s second visit to Australia, as it was scheduled for winter. However, none of the group were based there. Consequently, Brabazon travelled to Mount Tamborine in south-east Queensland to seek advice from an acquaintance, the prominent poet Judith Wright. Wright suggested he investigate properties around Buderim, north of Brisbane. Brabazon soon located a rundown pineapple farm on the hilltop at Kiels Mountain, near Woombye, which Meher Baba endorsed.

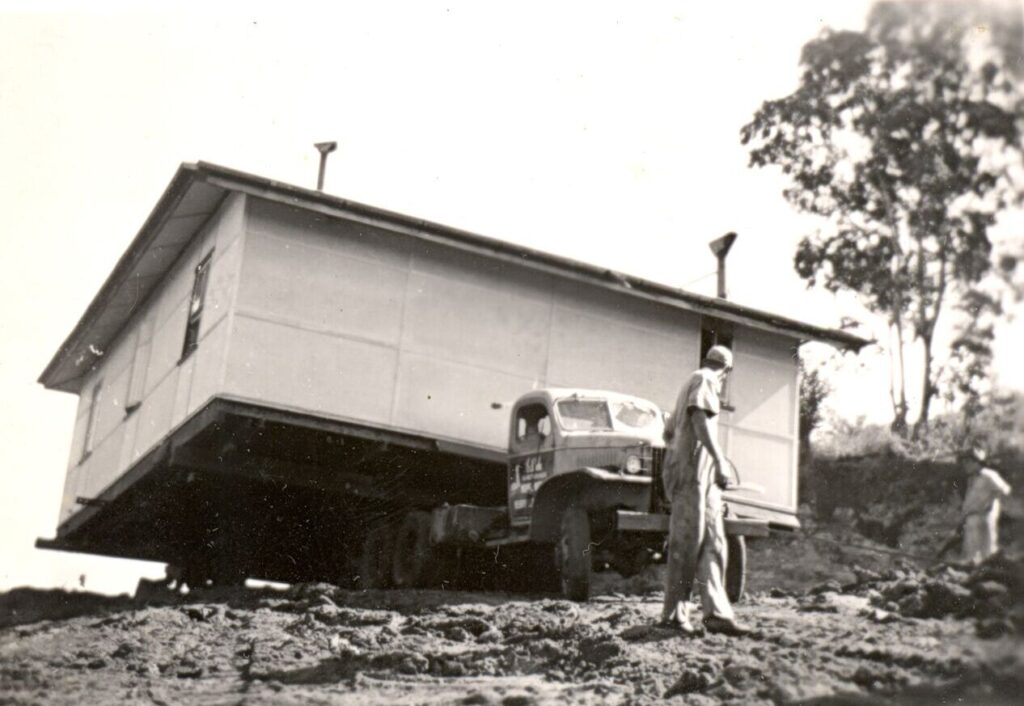

Creating the new centre within a few months posed serious challenges for the tiny group. People had to travel or relocate from their homes in Sydney or Melbourne if they wanted to assist. The property had no power and no running water, and building work was hampered by rain and mud. Nevertheless, roadways were dug out and buildings erected in time for Meher Baba’s visit with four of his disciples coming with him from India. Meher Baba stayed on the property from June 3–6, 1958, and he personally named it ‘Avatar’s Abode’. This was the first visit of an Indian spiritual leader to Queensland.

Although the property was gifted to Meher Baba, he returned it to Brabazon and reimbursed those who assisted in paying for it, stating he ‘held neither goods nor property’ (Grant 1987: 101; Le Page, 1993: 114). Meher Baba instructed two families to live there and farm the property. Subsequently, he would ask other families and individuals to live there or assist. Most especially, in 1967, Meher Baba called Bill Le Page (at the time Francis Brabazon’s main assistant) to India specifically to initiate a new phase. Soon after, there was a major swelling of public interest in Meher Baba in Australia. By the mid to late 1970s, Baba groups had developed in all state capitals and several rural areas.

Avatar’s Abode, meanwhile, became a transit or meeting point for youth investigating alternative and Eastern lifestyles and spirituality. Until the mid-1970s, there were no other centres of this type on the Sunshine Coast, although the region was fast becoming an epicentre for youth exploring an alternative lifestyle.

Francis Brabazon lived at Avatar’s Abode from June 1958 to January 1959, and then lived with Meher Baba in India for a decade, until soon after the latter’s death in 1969. When Francis returned to Avatar’s Abode, he remained there until his own death in 1984 and was buried on a slope near the Kiels Mountain summit.

Avatar’s Abode is strongly associated with Brabazon’s creative work as a poet, particularly the completion of his major work Stay with God (1959). Other books he published while living there were The Word at World’s End (1971), In Dust I Sing (1974), The Wind of the Word (1975), Four and Twenty Blackbirds (1975), The Silent Word (1978), and The Golden Book of Praise (1982). Brabazon encouraged visitors to produce music, poetry, drama, and art, especially as vehicles for celebrating Meher Baba and his messages.

Between 1979 and 1984, Bill Le Page’s Meher Baba Foundation Australia created the layout that Avatar’s Abode retains to this day. Much of the roads, cabins, landscaping, and other features were added at this time. Followers moved onto or near the centre, forming a small community along Meher Road. Avatar’s Abode Trust was formed in 1984 to hold the property in perpetuity. During the 1980s and 1990s, several of Meher Baba’s close disciples from India and the USA visited and stayed for days to weeks at a time.

Since the 1990s, more buildings, access roads and gardens have been added, along with facilities for preserving archives and relics. Over recent decades, the population of Australia’s Baba lovers is increasingly concentrated around the Sunshine Coast region, having moved up to be near Avatar’s Abode. Nevertheless, small groups remain in Sydney and Melbourne, and to a lesser extent in Brisbane, Canberra, and Perth.

A visitor’s guide to Avatar’s Abode

The summit of Keils Mountain is an ancient volcanic outcrop. Here and there, and in feature walls, the boulders that once covered Avatar’s Abode can still be seen. Much of the property is a flora and fauna reserve of grey gum and stringybark forest, with pockets and gullies of rainforest, blue gum, blackbutt, and wet sclerophyll. There are short walks to views over the east and west, and a circuit track through the bushlands.

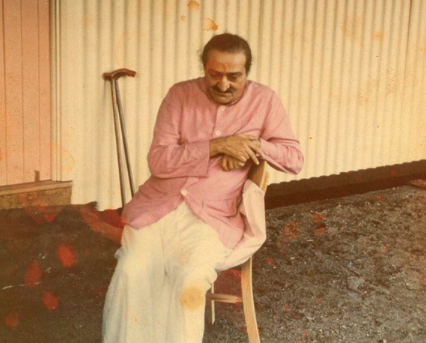

At the centre of the property lie a set of fields, gardens and buildings that form the focus of the Abode’s activity. Baba’s House is particularly important, as it holds the room (‘Baba’s Room’) where Meher Baba slept and gave individual interviews. It has all its original furniture and is frequently visited by devotees. Today, the house hosts smaller meetings and an art gallery featuring works by Meher Baba artists. On one side is a relics room where personal items associated with Meher Baba are displayed. These include his sandals, one of his iconic pink coats, two of the alphabet boards with which he communicated, and items he used while at Avatar’s Abode.

Across from Baba’s House is the Meeting Hall, a shed where Meher Baba gave some talks and instructions, using hand gestures, during his 1958 visit. It features the raised concrete dais where he sat. The hall later became the property’s first onsite accommodation. Today it is used for dining, meetings and to display passages from Meher Baba’s messages.

Other features of the property include the original farmhouse which dates from the 1920s. It was moved down the hill slope to free its original site for Baba’s House, and was visited by him, serving as the kitchen and women’s quarters during his stay. Today it provides accommodation for visitors. There are also residences, dining and performance buildings, accommodation cabins — one of which was Francis Brabazon’s last home — and a Reception Centre. The latter was added in 1996 and comprises an office, bookshop, library, and archive. It holds one of the world’s most comprehensive collections of works and documents by and about Meher Baba (over 70,000 documents), and translations of most scriptures and literary classics of the world. These began as the Sufi library of Baron von Frankenberg and were expanded into source materials that Francis Brabazon used to create his writings and music.

The centre is open to the public and sees a daily stream of visitors, most being local devotees. There are monthly coffee and cake mornings open to the broader community, and it is occasionally used for weddings and funeral commemorations. Most of the year, Avatar’s Abode is a quiet retreat where followers visit or stay, or where people come to learn more about Meher Baba. Annually, between 100 and 150 people stay for short periods in the on-site cabins. Rooms or buildings around the property serve as venues for meetings of committees and interest groups related to Avatar’s Abode and ongoing work.

Annual events see larger gatherings or celebrations, drawing visitors from all over Australia and overseas. These include Silence Day (July 10, marking when Meher Baba began his silence), Amartithi (January 31, the date when Meher Baba died or ‘dropped his body’) and Baba’s Birthday (February 25). Baba lovers also celebrate Easter and Christmas at Avatar’s Abode and invite all persons neighbouring the property. ‘The Anniversary’, held in early June each year, is the oldest continuous non-Christian festival on the Sunshine Coast. It is held to commemorate Meher Baba’s 1958 visit. Anniversary programs include talks, meals, special guests, sports, games, dramatic performances, workshops, music, exhibitions, films, and communal art, all broadly focussed on Meher Baba and spirituality. Hundreds of people attend the Anniversary, many being billeted by local Baba lovers living on streets near Avatar’s Abode.

… it is common for Baba lovers to maintain silence on Silence Day, to repeat Meher Baba’s name, and to engage in readings, music, poetry, and other activities that help them remember him. Many display photos of Meher Baba in their homes.

Baba lovers and the Queensland community

Meher Baba did not lay down a set of precepts or practices, maintaining that any approach to spiritual truth needed to be individual. Thus, followers’ practices are highly individualised. Even Indian centres are noted for a lack of structured programs. Nevertheless, it is common for Baba lovers to maintain silence on Silence Day, to repeat Meher Baba’s name, and to engage in readings, music, poetry, and other activities that help them remember him. Many display photos of Meher Baba in their homes.

Meher Baba emphasised the importance of selfless service to others. Consequently, Baba lovers often choose to work in fields such as medicine, education, psychology, naturopathy, minority rights, therapy, and treatment of substance abuse. Some have developed their own services and businesses on the Sunshine Coast, elsewhere in the state or nationally, but typically on an individual basis. These have included bookshops, cafes, naturopathic clinics, a halfway house for victims of domestic violence, a music therapy centre, and child welfare. Other ‘Baba lovers’ have been active in the development of Sunshine Coast alternative land co-operatives such as Starlight and Crystal Waters.

Australian Baba lovers have been especially prominent in the arts because Meher Baba identified the arts as ‘one of the sources through which the soul expresses itself and inspires others’ (Meher Baba in Kalchuri, 2001: 1631). Some followers like Oswald Hall, Maria Olsen, Katie Pye and John Parry became accomplished graphic artists while others became well-known musicians (Richard Lockwood of Tully, Sam Saunders of Muzika), or film actors (such as Peter Sumner). Others helped develop multicultural or multifaith programs. Australian Baba lovers have been active in organizing aspects of the Woodford Folk Festival, the Sacred Music Festival, and the Religion, Literature and the Arts conferences formerly based at the University of Sydney.

With thanks

The author extends his appreciation to those in the Meher Baba community who generously assisted with checking and correcting historical components of this essay: Avatar’s Abode Trust, Meherose Borthwick, Bernard Bruford, Jo-Anne Bruford, David Hobson, Jennifer Keating, Ross Keating, Bill Le Page, and Diana Le Page.

Sources and further reading

Anzar, N. 1974. The Beloved: The Life and Work of Meher Baba. Ahmednagar: Sheriar.

Eaton, R. M. 1978. Sufis of Bijapur 1300–1700: Social Roles of Sufis in Medieval India. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Ernst, C. W. 1997. The Shambhala Guide to Sufism. Boston: Shambhala.

Grant, J. 1987. Practical Spirituality with Meher Baba. Sydney: Merwan Publications.

Kalchuri, B. 2001. Lord Meher (Meher Pradhu): Meher Baba Avatar of the Age Manifesting, V (1932 – 1934). Myrtle Beach: Manifestation Inc.

Keating, R. 2002. Francis Brabazon: Poet of the Silent Word – a Modern Hafiz. Beacon Hill: World Axis Press.

Kerkhove, R.. 2002. ‘Authority and Egolessness in the Emergence and Impact of Meher Baba (1894-1969)’, PhD thesis, University of Queensland.

Kerkhove, R. 2007. ‘Unstructured networking in a charisma-based new religious movement: the ‘Baba lovers.” Australian Religion Studies Review 20, 2: 159–74.

Le Page, W. 1993. The Turning of the Key: Meher Baba in Australia. Sheriar: Ahmednagar.

Robbins, T. 1969. ‘Eastern Mysticism and the Resocialization of Drug Users: The Meher Baba Cult’, Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 8, 2: 308–17.

Wagle, N. K. 1997. ‘Hindu-Muslim Interactions in Medieval Maharashtra’, in G-D. Sontheimer, H. Kulke (eds), Hinduism Reconsidered. New Delhi: Manohar, pp. 134–52.

Related articles

![[image of 'Baba-lovers' at Avatar's Abode, n.d.]](https://qareligion.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/IMG_7647-e1680583623737.jpg)