The Ganesha Temple in South Maclean: Community, diversity, and devotion

The Sri Selva Vinayakar Koyil is a significant and popular site in the Brisbane religious landscape. It welcomes an increasingly diverse community of Hindus who attend to make social connections, to learn, to celebrate, and to express their religious devotion. The temple’s success and diversity are the result of a deliberately inclusive approach to temple community building and management.

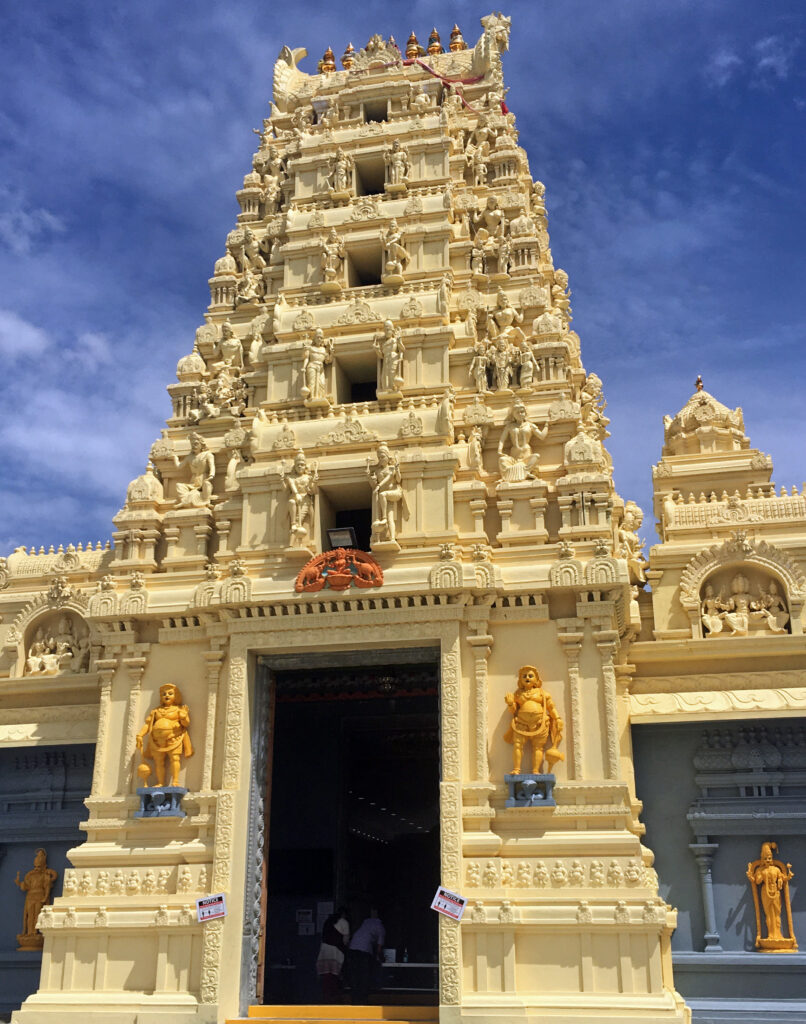

The commanding silhouette of the Sri Selva Vinayakar Koyil’s (SSVK) entrance gate, rising out of characteristically Australian bushland, is a striking feature in the otherwise unremarkable semi-rural suburb of South Maclean, Queensland. The distinctively South Indian style temple, situated on a large block of land bordered by the Mt Lindesay Highway and not far from the Logan River, is impressive in both its size and ornamentation. This Dravida inspired structure features a plethora of gods, demons, and guardians in its iconographic scheme, arranged within complex tiered aedicules . These aedicules are features of the square stepped vimanas, which take on a ‘piled up’ look as they form the pyramidal structure of this South Indian style temple (Hardy, 2007: pp; Orr, 2010: n.p.).

Upon entry via the main doors at the base of the towering entrance gate (gopura), devotees attending during ritual worship encounter a vibrant sensory environment — the smell of camphor, the amplified music and chanting by the priests, the flames of lamps being moved in front of the central shrine, and the colourful forms of the deities housed in shrines on every available surface. The primary deity to which the temple is dedicated is the elephant headed Selva Vinayakar. Flanking Vinayakar in their own shrines are Sri Amirtha Gadeshwarar, a form of Shiva, and Sri Abirami, a form of Parvati. The iconographic program of the inner temple includes an impressive variety of deities from both the Shaiva and Vaishnava families of Hindu gods, along with less expected shrines like the one dedicated to the well-known Bengali saint Ramakrishna.

First conceived and established by a management committee, the Hindu Ahlaya Sangam Qld Inc. (HASQ), the current form of the temple was consecrated and opened for worship on the 1st of May 2015. It was preceded by a more modest building on the same site in use from 1995 onwards. Designed and built by a specialist temple architect recruited from Tamil Nadu, India, and employed in Queensland for the duration of construction, the new temple cost between three to four million dollars. The temple’s property provides housing for the resident full-time priests in a separate dwelling. The site additionally features a cafeteria, detached outdoor ritual and processional spaces, a flock of resident peacocks, and a fenced off area for the temple chickens and cow.

While members of the temple’s management committee, many of the volunteers, and regular attendees are mainly of Sri Lankan origin, the temple is patronised by a wide variety of Hindus. While primarily facilitating a Tamil approach to worship, the HASQ has taken a deliberately inclusive and ecumenical approach in the years since the temple’s establishment in the early 1990s. This inclusiveness has led to the development and gradual expansion of a diverse temple community.

Ritual and devotion

Hindu temples attract devotees for a broad variety of reasons, such as devout prayer, socialising, serving the community, or simply enjoying the food served during festivals. One of the most important functions of the Sri Selva Vinayakar temple, as many of its devotees express, is providing an authentic feeling public space for the expression and performance of devotion (bhakti). Bhakti is expressed by Hindus through diverse practices. Indeed, it entails an attitude of devotion to the deity, service, and friendliness in all of life’s activities (Narayanan, 2010: 716). Many temple attendees emphasise the particular significance of visiting with their gods at the temple:

And to me personally … I feel that whatever hymns I’m saying or the prayers I do at home, I see god there. And I have to go and see him … as a human being, I have to go and see my god there, that’s all. (Sita, 2021: Interview)

Sita expresses what many attendees note as an important function of the temple, to provide access to the gods so that they may see and visit with them. This act of seeing the gods reflects the concept of darshana (seeing and being seen by a deity), often expressed by temple attendees in terms of visiting with the gods or catching sight of them during rituals (pujas). The Sanskrit word darshana, commonly translated as ‘seeing’ or sometimes ‘auspicious sight’ of the divine, denotes one of the key acts of religious worship common to many Hindus (Eck, 1985: 3; Valpey, 2012: n.p.). Diana Eck argues that the ‘central act of Hindu worship, from the point of view of the lay person, is to stand in the presence of the deity and to behold the image with one’s own eyes, to see and be seen by the deity’ (1985: 3). Although most Hindus maintain a domestic shrine containing small statues or printed images of their favoured gods and goddesses, the experience of taking darshana at a temple is often more highly valued. As Sita says, ‘I have to go and see my god there’. The difference lies in the ritual process of creation, consecration, and installation that each statue of a deity undergoes. Such a statue, often referred to by Hindus as an idol, is known in Sanskrit as a murti. The term murti can mean both ‘a form, body, figure’ and ‘an embodiment, incarnation, manifestation’ (Eck, 1985: 38). Thus, the term expresses the belief that a murti is more than a representation, it is the embodied deity itself.

The murti is only considered the fully embodied god once it has undergone a complex process of consecration (abhishekam) and installation (pratishtha) rituals, culminating in the infusion of the ‘breathlife’ (prana) and the opening of the (until this point sealed) eyes (Eck, 1985: 52–53; Clothey, 2006: 46–47). While describing the installation in 2021 of a new murti at the SSVK, a temple attendee named Reshika clearly defined the difference:

You could just buy an idol [murti], say Ganesha, from any markets or from a store which is selling these. That would just be like a piece of art. But when it is installed in a temple, a certain procedure is followed, certain rituals are done. So, it has to be sanctified and then they feel that because the priest has knowledge of the scriptures, he does those rituals. It’s a belief that now that idol has become a deity and that deity has certain powers.

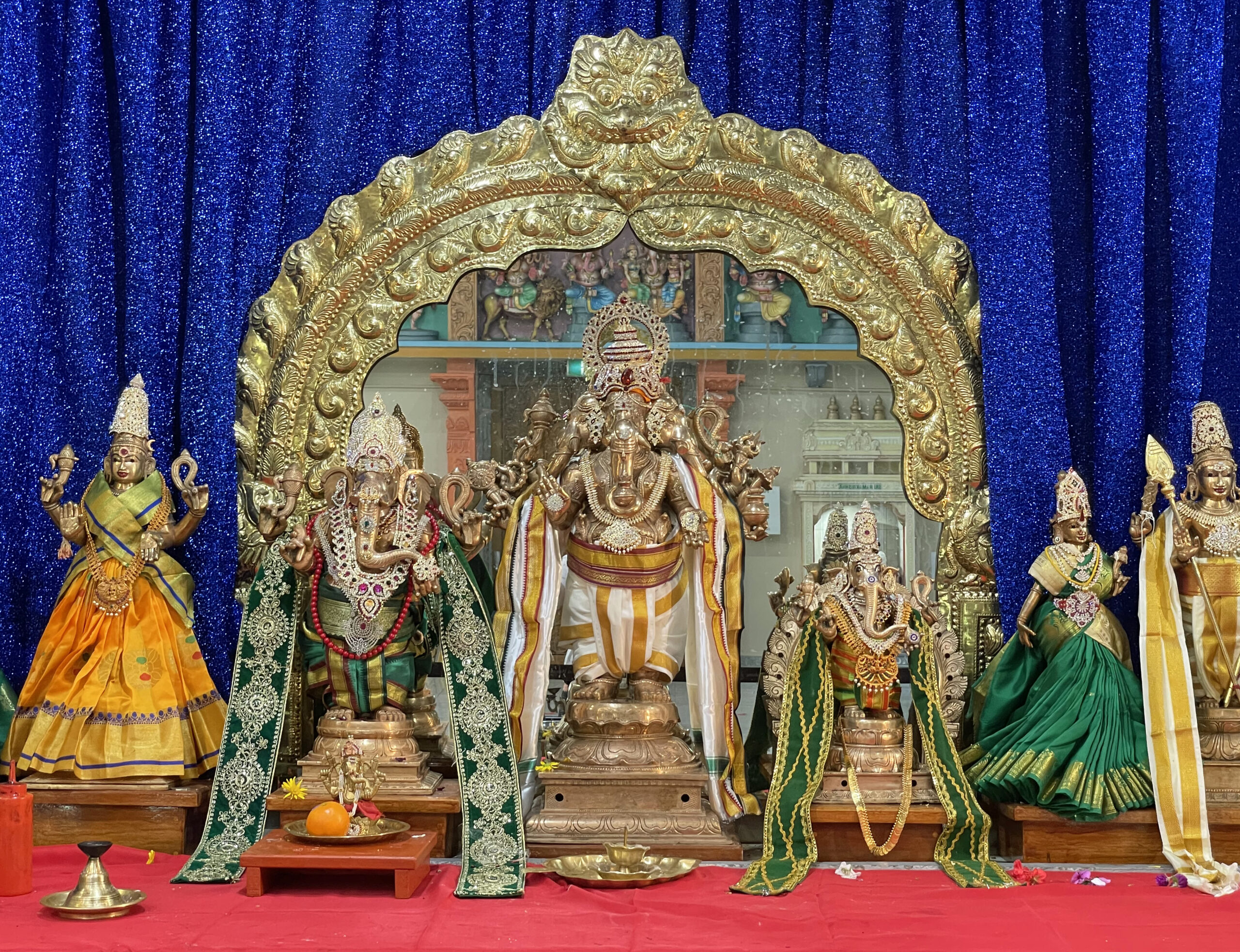

Figure 2: Utsavamurtis housed in the Vesantamandapa shrine within the Sri Selva Vinayakar Koyil (Jess White).

The consecration (mahakumbhabhishekam) of this new murti on the weekend prior to the SSVK’s Annual Festival led to a particularly well attended three-day ceremony. The murti in question was an utsava, ‘festival’, Panchamukha (‘five faced’) Vinayakar, who is portable and thus able to be taken outside the temple on procession. As one devotee noted, this murti represents a particularly strong aspect of Ganesha. The god’s strength was valued, in this instance, for his role as a remover of obstacles (Brown, 1991: 14). The weekend-long mahakumbhabhishekam featured a long series of pujas and offered the community many opportunities to participate in rituals and to approach the gods in a rare and intimate manner.

The new Vinayakar was dried off by the head priest and put to bed. I had watched the priests earlier make up a bed with bed sheets, pillows in pillowcases, and place ritual objects throughout. They lay the new god down in bed and tucked him in. The devotees could then circumambulate him and touch the bed or the murti reverently. I decided, at the encouragement of those around me, to do this and it felt like a rare privilege … Rarely do you get the opportunity to come so close to the murtis in the temple and see them from all angles. (Jessica White, 2021: Field Notes)

Many temple attendees noted that in South Indian temples only the priests are permitted to touch the murtis. But on this occasion, devotees were invited to touch and to take part in various stages of abhishekam (consecration) rituals such as pouring wheat chaff or blessed water over the new god. This seemingly emotional consecration event left me with an unforgettable impression:

As the head priest took the pot, he closed his eyes and chanted with passion. He seemed especially focused in this moment. As he poured the contents of the big kumbha [ritual pot] over the murti the whole crowd seemed to be keenly fixated on the ritual. To me, there felt like an electricity in the air, like the culmination of all the rituals over the three days had come to a focus and the people felt it. There were cheers and many hands pressed together in anjali as the ritual concluded. (Jessica White, 2021: Field Notes)

The rituals served to bridge the physical space between devotees and their god, providing an uncommonly intimate opportunity to experience and express bhakti. Through participation in the abhishekam rituals, participants served their god in a manner usually reserved for the priests. This type of affectionate service, expressed symbolically through simple domestic acts like bathing, ‘most directly convey the devotion of bhakti’ (Eck, 1985: 47). Once the deity is embodied in the murti, devotees could then take the darshana of the god they had welcomed to their temple. The cheers and happy faces observed during the final day of the consecration reflected the celebratory and inclusive feeling of this ritual.

Going physically to the temple to take darshana with one’s god, having the rare opportunity to touch and personally serve the gods, and sharing all of these experiences with fellow devotees are experiences consistent with some of the oldest notions of embodiment and community within the Tamil Shaivite bhakti tradition. The form of religious practice followed by many Tamils today primarily combines Shaiva Siddhanta philosophy and the devotional (bhakti) movement, expressed through the poetry of the Tamil bhakti saints (Jones, 2020: 175; Belle, 2017: 41–42). The focus on embodiment in Tamil Shaivite bhakti can be traced to the early hymnists, referred to within the tradition as ‘the three’ (muvar) (Pechilis Prentiss, 1999: 9):

In defining bhakti as a religious path, the mūvar represented bhakti as a theology of embodiment. They embodied bhakti in their own experiences, their visions of Ṥiva, their pilgrimages to Tamil towns, and the community of bhaktas [adherents of bhakti].

The SSVK facilitates a Tamil derived embodied bhakti practice, experienced and expressed collectively, in a manner that is generally not possible in the home. Bhakti expressed in a community setting recalls the earliest ideals of the muvar and, Clothey (2006: 14) argues, ‘links one to one’s community and to one’s lineage symbolically’. The ability to visit a temple containing ritually consecrated and installed murtis supports the continuation of familiar embodied practices that would be part of everyday life in devotees’ homelands. Collective experiences, such as the consecration of a new murti, provide this Brisbane temple community with a time to come together, to feel solidarity, belonging, and to celebrate.

Inclusivity, community, and celebration

Despite an evident focus on Tamil style worship, especially during events like the mahakumbhabhishekam, the SSVK also facilitates more diverse styles of worship. In doing so, it accommodates attendance by a broad range of Hindus, which has resulted in a diverse temple community. This appears to have been, at least in part, a deliberate strategy of the management committee. To encourage a diverse temple community, an early decision was the selection of the popular god Ganesha as the primary deity. Aadhi, a member of the HASQ said:

… see, South Indians worship lord Murugan, but Ganesha is worshiped all over the world, even in the Muslim countries … in north India too. So, we thought if the temple supports darshan there’ll be more people coming in. So, we want to have lord Ganesha … so, more parties can come in and [it would] be a more popular temple. (Aadhi, 2021: Interview)

Despite most of the founding members of the community being either Sri Lankan or South Indian Tamil, there was evidently an early desire to welcome a broader community to the temple. As migration to Queensland has increased, the temple has enjoyed growing temple attendance in general, as well as greater ethno-linguistic diversity among those who visit. Devotees come together to worship, from a variety of national and regional backgrounds, speaking a broad range of South Asian languages. While temple attendees are usually multilingual, they sometimes do not share the same language with those around them. This has led to a recognition, by the HASQ and the temple priests, that English is a useful common language for many communications within the temple and in its popular adjoined cafeteria. The use of English at the SSVK can therefore be seen as an accommodation and promotion of diversity.

Another key strategy for encouraging diversity at the SSVK is the inclusion of a broad range of festivals. The temple’s calendar includes a mixture of festivals that in some cases might be considered Tamil in orientation, for example Thaipongal and the Annual Festival (also known as Thiruvizha). Others reflect those commonly celebrated by many Hindus, including Ganesha Chathurthi, Navaratri, and Diwali. These festivals, and many others, are celebrated almost constantly throughout the year at South Maclean, with opportunities for devotees to worship a wide variety of gods at astrologically auspicious times. A number of these occasions attract especially large attendance and involve community participation, either through donations of funds or consumables, decoration of the festival murtis (utsavamurtis), cooking and serving food to their fellow devotees, and performances during the festival programs. Temple attendees value these occasions as time for the community to come together, to socialise, to celebrate, to offer service, and to express their religious devotion.

Figure 6: Lively procession during the Chariot Festival, part of the Annual Festival at the Sri Selva Vinayakar Koyil, 2021 (Jess White).

During 2021, a wide variety of festival days and evenings, both events with a Tamil focus (including Thaipongal, Thaipusam, the Annual Festival, and Chariot Festival), and those considered more pan-Hindu (including Shivaratri, Ganesha Chathurthi, Janmashtami, and Diwali) were held, even during the height of the COVID19 pandemic, though this required adaption to public health advice and restrictions. The Chariot Festival, held in April on the ninth day of the SSVK’s Annual Festival (Thiruvizha), which also coincides with Tamil New Year, involved one of the largest groups of devotees gathered at one time. It was a colourful day, bustling with ritual and social activities:

The procession then moved out to the front of the temple where kavadi [decorated wooden frame] carriers danced along with the musicians. The musicians altered the tempo of the music periodically, giving the dancers varied periods to slow down, and periods to dance more wildly. Soon, the Panchamukha Vinayakar utsavamurti was lifted onto the heavily decorated chariot and two large ropes were attached. Along the ropes a great many devotees lined up and the procession began to get underway. Many men performed vratas by rolling on the ground lengthways behind the procession all the way around the temple. There was an excitement and celebratory air to the day. People smiled and greeted each other, saying ‘Happy New Year’. They hugged as they struggled to negotiate arranging their masks, saris, and children. (Jessica White, 2021: Field Notes)

The Chariot Festival is notable for its inclusion of the broader temple community. Whitaker writes that during the Annual Festival at the Periya Bhadrakali Ammal temple in Sri Lanka, ‘days of the festival were sponsored by the villages, caste groups, and lineages that, theoretically, were assigned to the specific jobs, tasks and status positions needed within the social system mapped out by the god, Murukan …’ (2015: 1378). This system is intrinsically connected with the local territory surrounding the temple, its cosmology, and its long social history. In diasporas, the groups supporting temples must adapt to their various, and generally quite different, circumstances. At the SSVK, for example, support and inclusion are accomplished by dividing Brisbane’s city and close regions into area groups, with each group sponsoring one day of the festival. Each year, festival programs detailing which suburbs belong to which group are distributed. Key contacts for each group are included so that anyone who wishes to be involved in the planning and finance of decorations, performances, and shared meals (annatanam), may get involved. A committee member explained the system, affirming that ‘because there are too many people, so you’ll have to give a chance to everybody. So, this area people on [a] certain day, like that, so everybody is having a chance.’ This practice of inclusion, allowing the community to feel a tangible sense of solidarity, belonging, and pride, was also expressed by Dinesh:

And there is a huge community involvement, huge [his emphasis] community involvement. It is just not the temple. So, … each suburb will be doing it, they have the annatanam, they make garlands, everything is done. So, it’s amazing when you see even the way the lord is decorated. The massive amount of [effort], and it’s all done by volunteers … (Dinesh, 2021: Interview)

Festivals, like the Thiruvizha, also facilitate a familiar cultural environment which supports attendees’ ethnic identifications. The Chariot Festival was filled with colour, sound, and excitement, or as one woman expressed, ‘It’s colourful and chaotic, but a wonderful celebration’. Dressed in richly coloured and , devotees assembled inside the temple, some spilling out through the open side doors, to watch the extended pujas, while the smells of the coming lunch wafted across the temple grounds. An older man remarked on the day that being surrounded by such sights, sounds, and scents, allowed him to feel that ‘it’s just like being at home’. Another devotee expressed similar sentiments when writing about the temple: ‘The yearly temple chariot [festival]–I like this event, because on this day I get to see all my friends at the same time, meet new friends, and it’s very colourful that day.’

On festival days temple attendees surround themselves with familiar ethnic, cultural, and religious practices, food, dress, and music in a mode of celebration and public expression. For Tamils, the familiarity of the Thiruvizha recalls a sense of shared history, affirming their group identity, reminding them of life in their homelands, and strengthening their sense of community. For other Hindus, festivals with broader appeal, such as Shivaratri, Navaratri, or Diwali facilitate an experience that is ‘familiar enough’ in its religious and cultural appeal to also feel that it is ‘just like at home’. Whichever cultural and religious aspects devotees identify with, these are supported, recognised, and celebrated by the whole community. These sentiments were expressed succinctly by a temple attendee: ‘Coming regularly to the temple and participating in different festivals … gives us a feeling of belonging in this community and respects our identity as a Hindu.’

Old communities, new communities

Despite occasional frictions, temple attendees report positive experiences in relation to the growing diversity of the community. Diversity at the temple was seen to offer novel opportunities to meet Hindus from differing backgrounds, with whom attendees could form friendships and share unique cross-ethnic religious knowledge. Even among Tamils, diverse national, regional, and religious identifications are possible and a common feature of Tamil groups in diasporas. This type of national diversity is a feature of the SSVK community, with a high number of temple attendees having migrated from both India and Sri Lanka and identifying as Tamil speaking. Dinesh, a Tamil speaker from India, explained:

… also we made quite a few Sri Lankan friends. Because we wouldn’t have had much contact with the Sri Lankan religious people. A lot of people who are so religious and so involved, we would not have known them.

Nantha, a Sri Lankan devotee, described how meeting Hindus with diverse identifications and backgrounds had enable him to expand his religious knowledge:

[When] you walk into this Brisbane Hindu temple, you would not just see Tamil people. You would see people from South India, North India, Nepal, Fiji. So, they follow the same religion, but they are from different ethnic groups, they speak different language, follow different customs. Because even when it comes to Hinduism, people from those different ethnic groups, follow Hinduism in a different mechanism … So, only a multicultural society like Australia or a different world other than your own would give you this opportunity to learn more what you don’t know. Because I learn new things from Hindus from Nepal, a different custom that we would not even see in South India or Sri Lanka … So, this is the only way that we can talk and interact with people and know more about Hinduism.

Dinesh and Nantha’s remarks support the notion that SSVK attendees see benefits in the management committee’s approach to inclusivity and that community members are, in some ways, embracing a sense of curiosity and openness to diversity.

By following a deliberately inclusive approach to temple building and management, the HASQ have developed the SSVK into a significant and popular site in the Brisbane religious landscape. For devotees like Sita, Reshika, Aadhi, Nantha, and Dinesh, the temple provides a space and focus for devotion, social connection, and learning. The wide variety of festivals celebrated offer them reminders of home and opportunities to celebration their ethnic heritage, along with the chance to serve both the gods and their community. Whether visiting once a year or once a week, the SSVK has become a central hub of religious life for an increasingly diverse community of Hindus.

With thanks

The information and interviews which form the basis of this article have been drawn from my MPhil thesis, completed in 2022. I wish to express my gratitude to the HASQ, SSVK priests, and all research participants. Without their assistance my research could not have been accomplished, particularly during such a challenging time. All names used in this article are pseudonyms.

Sources and further reading

Belle, C. V. 2017. ‘Tamil Traditions and South Indian Hinduism.’ In Thaipusam in Malaysia: A Hindu Festival in the Tamil Diaspora. ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute, 19-64.

Brown, R. 1991. ‘Introduction.’ In Ganesh: Studies of an Asian God, Robert L. Brown (ed), New York: State University of New York Press, 1–18.

Clothey, F. 2006. Ritualizing on the boundaries: continuity and innovation in the Tamil diaspora. Columbia, S.C: University of South Carolina Press.

Eck, D. 1985. Darśan: Seeing the divine image in India. Pennsylvania, USA: Anima Books.

Hardy, A. 2007. The temple architecture of India. Chichester Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Jones, D. 2020. Superdiverse Diaspora. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Narayanan, V. 2010. ‘Bhakti.’ In Knut A. Jacobsen, Helene Basu, Angelika Malinar and Vasudha Narayanan (eds), Brill’s Encyclopedia of Hinduism Online, 710–19.

Orr, L. C. 2010. ‘Temple: Form and Function.’ In Knut A. Jacobsen, Helene Basu, Angelika Malinar and Vasudha Narayanan (eds), Brill’s Encyclopedia of Hinduism Online, 496–510.

Pechilis Prentiss, K. 1999. The embodiment of bhakti. New York: Oxford University Press.

Valpey, K. 2012. ‘Pūja and Darśana.’ In Knut A. Jacobsen, Helene Basu, Angelika Malinar and Vasudha Narayanan (eds), Brill’s Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Leiden; Boston: Brill, n.p.

Whitaker, M. 2015. ‘Temples in Diaspora: From Moral Landscapes to Therapeutic Religiosity and the Construction of Consilience in Tamil Toronto.’ In S. D. Brunn (ed.), The Changing World Religion Map: Sacred Places, Identities, Practices and Politics, Netherlands: Dordrecht, Springer, 1363–83.

Related articles