Religion at the Moreton Bay Settlement, 1824–1842

The harsh military setting of the Moreton Bay penal settlement was an unpromising location for religious and spiritual life. Protestant or Anglican clergymen were only occasionally present, while Roman Catholic priests were entirely absent. Services were performed by a mixed bag of part-timers, layman substitutes, visitors, and travelling missionaries. For the population of convicts, soldiers, and officials, it seems that religious considerations were rarely entertained.

By Jennifer Harrison and Geoff Ginn

This is an 18 minute read, published June 2024.

By the mid-1820s the British penal colony of New South Wales had developed in all directions in the forty years since its founding. The frontier town of Sydney contained the basics of most essential services, while the ever-expanding rural districts were attracting a rapidly growing population. By this time, attempts to extend the British presence across the continent were continuing at Melville Island, Port Essington and Raffles Bay, while remote penal settlements had been established at Port Macquarie, Norfolk Island and Moreton Bay. The latter were places of ‘secondary punishment’ for repeat offenders, and were intended to be harsh to deter convicts’ misbehaviour.

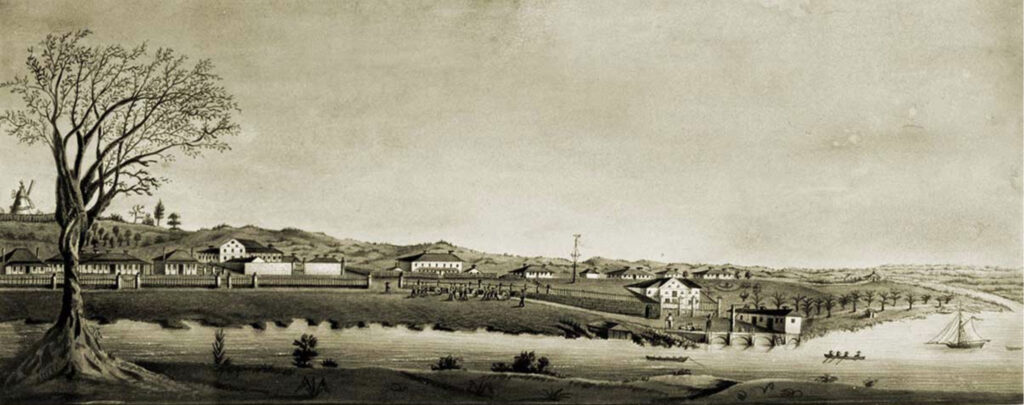

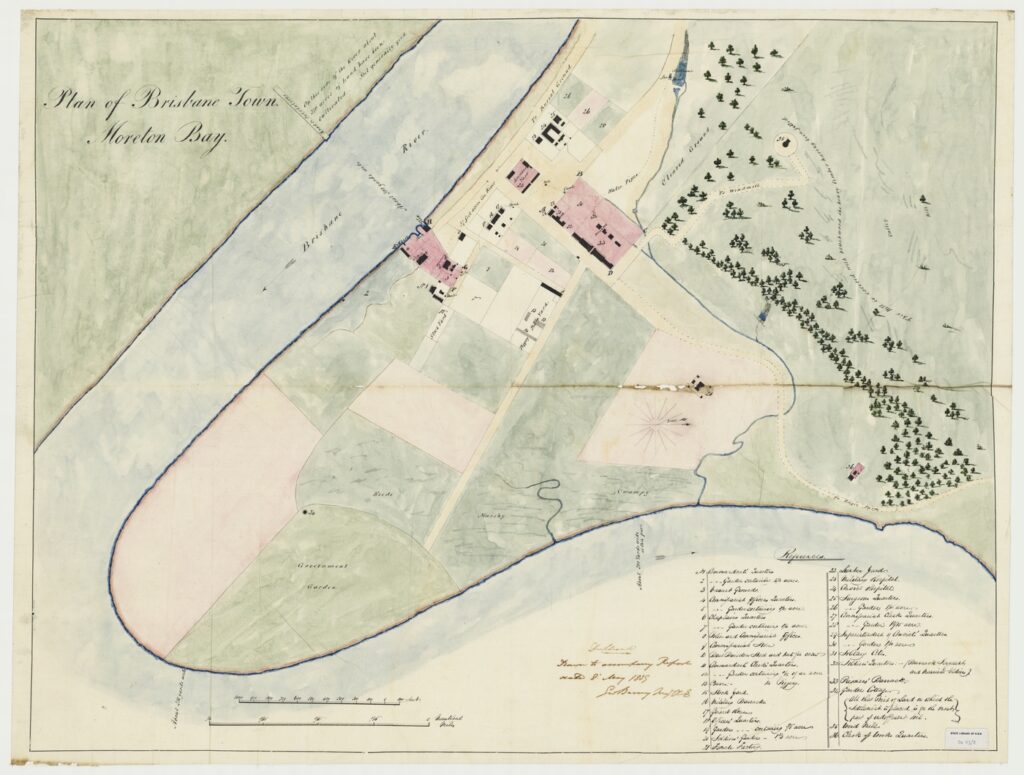

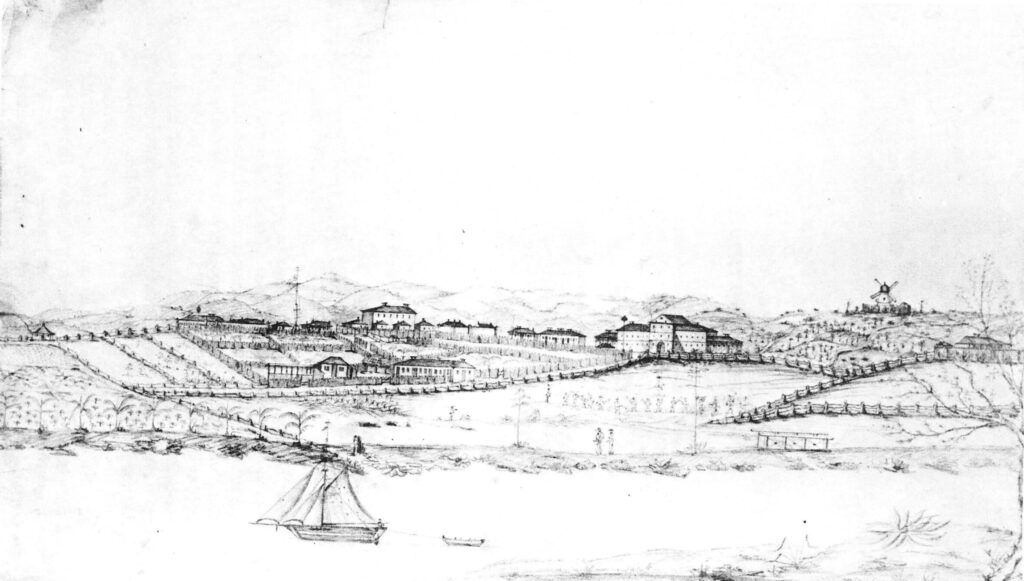

After the Surveyor-General of New South Wales, Lieutenant John Oxley, discovered the Brisbane River in 1823, the Moreton Bay settlement began at Redcliffe in September 1824. For various reasons it was moved upstream to the site of modern Brisbane in April-May 1825. This station operated until May 1839, when most convicts were returned to headquarters and three years later, in February 1842, the district was opened to free settlement.

As Brisbane Town took shape during these years, few ministers of religion ventured northwards. Although the 1829 Regulations for Places of Secondary Punishment provided for regular church services, for most of the time these were read by civilian officers such as assistant surgeon Dr Henry Cowper, the son of a Sydney clergyman who arrived at the Moreton Bay convict settlement in September 1825. In making this appointment, Governor of New South Wales, Sir Thomas Brisbane, recognised that illness was severely hindering the convicts’ ability to labour, and that medical support was imperative to provide the buildings and farm produce required by the settlement. In addition, the Governor acknowledged that the souls of prisoners, officials and military personnel required attention.

Even so, convicts’ spiritual needs, particularly of the Roman Catholics among the Irish convicts at the settlement, were not well succoured despite the regular church services required by colony regulations. Other than the stipulated Sunday worship, neither religion nor encouragement towards reformation seem to have been emphasised. Between 1825 and 1829 services were read by civil officers, with Cowper undertaking most of the responsibility. Despite all positive influences his well-respected father, Rev. William Cowper, may have imparted during his eldest son’s formative years, this reputedly hard-drinking, unprincipled reprobate was an unlikely role-model to advocate reformation. He remained at Brisbane Town until his dismissal in 1832 for unacceptably lax conduct and is remembered in the name of the Brisbane suburb of Coopers Plains. During this time, the first ordained clergyman to travel north was the Reverend Thomas Hobbes Scott, Archdeacon of New South Wales from 1824 to 1829, who accompanied Governor Ralph Darling’s party to Moreton Bay in June 1826. While in Brisbane, Scott baptised four children at the settlement including Commandant Patrick Logan’s recently born daughter, Letitia; he recorded the baptisms in St Phillip’s register in York Street, Sydney.

Although desirable, the presence of Protestant or Church of England clergymen as permanent residents at the remote colony was not easily achieved. There was a decided lack of clergy prepared to serve in New South Wales, and those with families who were ready to spread the gospel in the wilderness often clashed with implacable military commandants under whose administration they were obliged to serve.

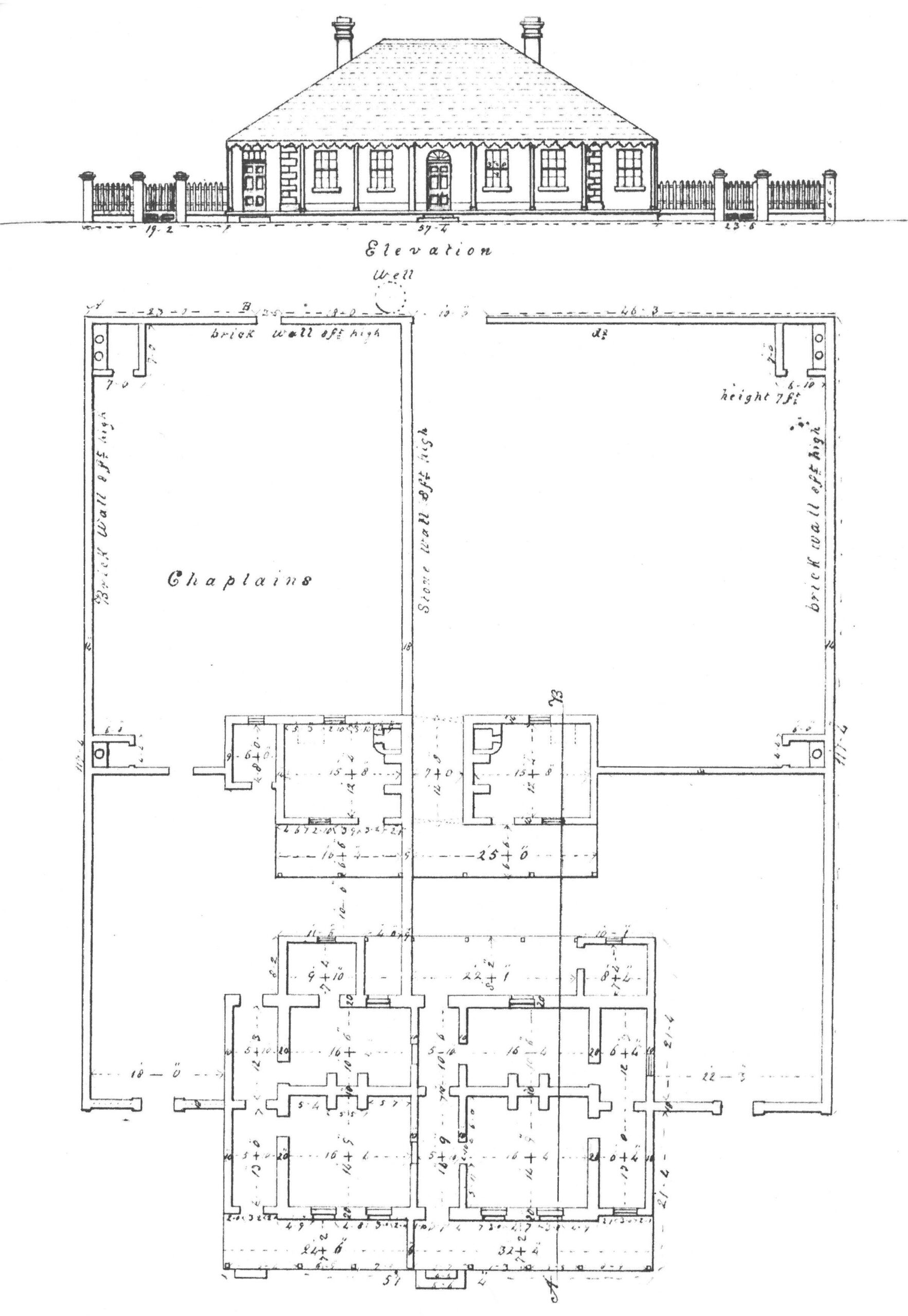

Despite plans to post John Layton as a catechist to Moreton Bay, no further Anglican clergy arrived until March 1829 when the Reverend John Vincent and his family reluctantly fulfilled his appointment to the penal station. He initially found that he was required to conduct services in the open air, during which ‘[g]reat inconvenience was experienced by every one from the intense heat of the sun,’ before approval was granted for a room in the prisoners’ barracks to be used (Steele, 1975: 105). Vincent’s duties also included baptisms and burials for both convicts and military, and supervising schooling for the children of prisoners, soldiers, and officials.

Together with his family John Vincent settled into the handsome chaplain’s cottage or ‘parsonage’ close to the commandant’s cottage and office, overlooking the river on what is now William Street. From the beginning, however, Vincent found fault with local conditions and was bitterly and constantly quarrelling with Captain Logan and other personnel. He was recalled within the year. Misunderstanding differences between rules and command structures at penal settlements when compared with his initial experiences at Parramatta probably contributed to the minister’s disillusionment, although he unhappily grumbled his way through later postings, finding little joy in persistent poverty, his large family, or his needy parishioners. Following his departure, just before Christmas 1829, the lay officials such as Cowper resumed their readings. Logan was clearly not anticipating an early replacement for Vincent when he granted Assistant-Surgeon James Murray half the chaplain’s house in May 1830 (Steele, 1975: 144).

For the seven years that followed the district was without the benefit of clergy, despite the very evident need for religious provision. Soon after Logan’s death, for example, in December 1830 his successor, Captain James Clunie, was ordered to arrange in Brisbane the execution of two thieving runaways, Charles Fagan and John Bulbridge. A Roman Catholic priest in Sydney, Father John Therry, unsuccessfully petitioned to attend, protesting that the two Irishmen would meet their deaths without the solace of any minister of religion. When access was denied, Therry did not travel to Moreton Bay and apparently never did visit the penal settlement. Thus any of the Catholic convicts or soldiers at Moreton Bay who were inclined to practice their religion only had access to their own private prayers.

Figure 3: Brisbane Town pencil sketch 1835, view from Kangaroo Point (National Library of Australia).

Religious distinctions at Moreton Bay

In 1820, when the Roman Catholic priest Father John Therry began his ministry in Sydney, approximately 6000 of New South Wales’s non-Indigenous population claimed Catholicism. By 1833 the number was 17,238 in a population totalling 60,794, boosted significantly by the influx of Irish convicts (O’Farrell, 1977: 23). Later census returns for NSW as a whole showed the proportion of Roman Catholics at around 28 per cent of a total non-Indigenous population of 77,096 (in 1836) and 128,726 (in 1841).

In Brisbane Town, the distant northerly region of the colony, the majority nominated Church of England or Roman Catholic affiliations. While the records relating to Brisbane’s convict population are complex and inconsistent, current historical research indicates that some 2,400 male convicts and around 144 female convicts were confined at the settlement. The main registers specify the religious affiliation of around 1800 of these, but not without ambiguity in the records. It appears that about 680–90 were Roman Catholic, while around 870 or so were marked ‘E’ for ‘English church’. Nearly 200 were marked ‘P’ which may have represented ‘Protestant’, but could also infer ‘Presbyterian’ — while only about 110 have the last designation marked explicitly. The many Scottish and Ulster Irish prisoners may not be accurately captured in these tentative figures. In addition, around 10-20 Jewish prisoners were incarcerated at Moreton Bay, while others are entered in the census as simply ‘pagans’. In addition to census returns, after 1826 religious affiliation usually was indicated on convict indents, as well as in the descriptions lists in the Chronological Register of Convicts at Moreton Bay (Queensland State Archives, Item No. 869689) and in the registers of admissions to Sydney Gaol (NRS 2514–15, 4/6360; 4/6428–38, Reels 850–3).

For the officials charged with governing Britain’s overseas territories, particularly during the prime ministership of the Duke of Wellington, their interaction with the Roman Catholic presence in the colonies was changing. This was an age of religious emancipation in Britain, and by extension in colonial outposts like New South Wales. In 1828 the Sacramental Test Act removed many civil restrictions on Roman Catholics, and the 1829 Roman Catholic Relief Act enabled Irish Catholic politicians such as the reformer Daniel O’Connell to sit in Parliament. Not surprisingly, however, discriminatory policies and attitudes remained. In New South Wales, Governor Richard Bourke’s reforms especially in education and religious policies stressed national rather than denominational control, discriminating against any concept of a ‘nationally established church’ (King, 1971: 226–43). When urging government financial support for the completion of a Roman Catholic chapel in Sydney in 1824, for example, Governor Brisbane, uncharitably and inaccurately, had advised Lord Bathurst at the Home Office:

Altho’ I am no advocate for the tenets, or doctrines of the Church of Rome, still I consider that in proportion as Roman Catholics increase, Priests should be sent for their spiritual instruction, as it is a remarkable fact of which perhaps your Lordship cannot be aware, that every murder or diabolical crime which has been committed in the Colony since my arrival has been perpetrated by Roman Catholics, and this I ascribe entirely to their barbarous ignorance, and total want of education, the invariable companions of Bigotry and cruelty, as well as the Parent of crime (Historical Records of Australia, Ser. 1: 11, p. 382, 28 October 1824).

If the number of Roman Catholic adherents at the Moreton Bay settlement tended to confirm the governor’s correlation between the lack of ‘spiritual instruction’ and crime, more correctly the greatest influencing factor in choice of religion would have been found in their Irish birthplace. Any aptitude for criminal behaviour was far more likely to have its origins in their social and economic condition within their home villages and towns and later, in the colony of New South Wales. Church of England teachings, meanwhile, did not appear to effectively diminish crime among Englishmen and women, any more or less than any other religious denomination.

For their part, any need for or acceptance of clergymen at the penal settlement by either Catholic or Anglican congregations cannot be estimated with any accuracy. Some may have had a strong faith and sincerely regretted their lapses. Most of them designated a religious affiliation when asked, but for a great number no formal link was noted. We should acknowledge, however, that any missing information could be due to clerical error or lack of transcription rather than an unwillingness to claim adherence to any creed.

Convict women and religion

At Moreton Bay, religion was imposed on the women, as for the male convicts, as part of their routine: little of its promised benefits appeared to influence their way of living or actions. Of the 144 individual women who served their sentences at Moreton Bay during the years of the settlement, sixty-four indicated their religion as English church or Protestant. Of these, seven including Mary Blackburn, Dorothy Huldie and Isabel/Elizabeth Strachan were most likely Presbyterian. The largest group, some eighty in number, were Roman Catholics according to the census and registry information noted above. Three Moreton Bay convict women had links with Judaism: Elizabeth Robertson and Catherine Keefe married Jewish convicts, while Mary Cohen may have been a London Jewess (Levi, 2006: 145).

These numbers show that throughout these years at Moreton Bay, the majority of women convicts were not able to partake in the formal worship available either in the town or at the agricultural outpost at Eagle Farm (where the women were primarily stationed). The desire to extend some soul regeneration to those geographic exiles who supported the English church never extended to the larger proportion of those who followed Catholicism, while the few Presbyterian adherents were subsumed within Episcopalian numbers. Indeed, apart from a few Christian expressions from the Quaker observers during their fourteen-day visit in 1837 (see below), the convict women of Brisbane Town never were recorded as having received any personal encouragement or prayers outside the prescribed reading of the regular weekly service.

Elsewhere many women convicts in Australia became servants in rectories and the households of chaplains, where they may have received moral inspiration from clergy wives. But at Moreton Bay, during the short period of John Vincent’s tenure in 1829, the ever-pregnant and debilitated Eliza Vincent was not in a position to contribute much joy. To take advantage of any privileges, prisoners needed to forge associations with these mentors which often proved a difficult task particularly for Irish Catholics who, having lived through the 1820s tithe wars in Ireland, openly despised Anglican churchmen. It is not that they were incapable of reading scripture themselves: parallels between Irish female convict skills and their literacy have been assessed and indicate that those who could read and write were estimated at 13.3 per cent for the unskilled rising to 30.9 per cent for the skilled workers (Oxley, 1996: Appendices A25 and A28).

Chaplains, missionaries, and clerical visitors

The spiritual needs of Moreton Bay were not entirely forgotten, however. Governor Darling, in one of his last letters to London written while homeward bound in 1831, advised that he had appointed a chaplain to Moreton Bay. This almost immediately was countermanded when his successor, Governor Bourke, advised that the requirement for clergy at stations was not applicable to Moreton Bay because ‘[c]ircumstances may, I think, induce me to recommend to Your Lordship to abandon the station before long.’ Yet by the end of 1832, the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies in London, Viscount Goderich, informed Bourke that chaplains ought to be stationed at Norfolk Island and Moreton Bay while numbers of convicts remained large and ‘destitute of religious instruction’ (Historical Records of Australia, Ser. 1: 14, p. 563).

The overriding problem remained securing sufficient clergymen to serve in the antipodes, particularly given ‘the state of society there, and the privations which they undergo in the course of their ministry.’ Bourke reserved appointing to the mainland station while he dithered with the decision to close the place (Historical Records of Australia, Ser. 1: 15, p. 542). Cowper was disgraced and dismissed in late 1832 when, in a locally-infamous case of misconduct, he and a visiting ship’s captain with others broke into the women’s barracks for convivial carousing with a group of female prisoners. Sunday services were thereafter led by Superintendent of Convicts Peter Spicer in Brisbane, Superintendent of Agriculture John Parker at Eagle Farm, and Deputy Assistant Commissary-General Stephen Owen, who commenced his posting in January 1834.

Given the impossibility of supplying religious personnel to all outlying districts when so few were recruited in England for colonial outreach, Governor Bourke gratefully sponsored other visitors thereafter. In March and April 1836, two Quaker missionaries, James Backhouse and George Washington Walker, held services at different depots throughout Brisbane and Moreton Bay during a short visit. Commandant Foster Fyans encouraged their interaction by assigning a junior officer as escort to accompany the two men to all parts of the settlement, permitting them to observe convict behaviour and treatment. Backhouse was particularly interested in the Female Factory on the outskirts of the town:

We had a religious interview with the women in the Penitentiary who are about thirty in number. As in most other cases, crime has been nursed by strong drink, which has occasioned their re-conviction and some of them seem far from being properly sensible of their miserable condition. We had however the message of mercy to convey to them, directing them to the convictions of the Holy Spirit in their own consciences (Backhouse, 1838: 55).

On 4 April, accompanied by John Parker, Backhouse and Walker visited Eagle Farm and observed forty women undertaking field labour. They again felt satisfied with their ministry:

Though these women are twice convicted and among them are no doubt some of the most depraved of their sex, yet they received from us a religious visit with gladness; and the sense of the Divine presence was with us (Backhouse, 1838: 58).

Buoyed by their apparent success, the two returned to Eagle Farm five days later when they left a selection of tracts for the women’s use. Noting a lack of books in general, and bibles in particular, for the women to use, they felt these were thankfully received. Fyans was more sceptical about the positive effects of the Friends’ ministrations. He wryly observed that ‘The women at Eagle Farm underwent great scrutiny: many notes made; but no beneficial result followed’ (Fyans, 1986: 147). The missionaries left the settlement on 11 April, and Backhouse subsequently made several recommendations and arranged for tracts and testaments to be delivered.

The following year, in February 1837, the Reverend Thomas Atkins, an Independent minister on his way back to Sydney from Norfolk Island where he had been chaplain, also conducted a couple of services at Moreton Bay when his boat called to collect grain. He noted that ‘on the Sunday [12 February 1837] during my stay in Brisbane, I performed Divine Service at the barracks, in the presence of authorities, the soldiers and the prisoners.’ (Atkins, 1869: 59) Commandant Fyans was not, however, favourably impressed when the parson presented himself for dinner in “an old dressing gown, very long and very aged; a pair of old boots, cut into slippers; with a large muffler round his neck, hair careless, with a stupid looking countenance”. During his stay, forgetting to say grace, the visitor supped extremely generously but exhausted the settlement’s hospitality by his excessive fondness for large quantities of porter, claret, and brandy. According to Fyans’ recollections, Rev. Atkins spent most of his time at the settlement delirious, in his room trying to recover in time for the next meal (Fyans, 1986: 174–75). Misrepresentations evident in the minister’s written account describing the numbers of residents and his claim that Moreton Bay was a settlement reserved for female recidivists can be more easily understood if Fyans’ assessments were correct.

Figure 5: Prisoners' Barracks, east frontage along what is now Queen Street, 1838 (Queensland State Archives).

At around this time, arriving in May 1837, the far more diligent and promising figure of Rev. Johann Christian Simon Handt appeared on the scene in Brisbane Town. Born in Saxony, Germany, Handt had been sent to New South Wales by the Church Missionary Society and from there to work among the Aborigines at Moreton Bay. Rev. Handt soon became responsible for most services and superintended educational arrangements after gaining Governor Bourke’s assurance that he would receive wages. He too, conducted baptisms and burials, although a later visitor commented on his broad German accent and the difficulty congregations experienced in understanding him.

At the end of April 1839, just before the convicts were removed and the Brisbane settlement wound down, Handt’s wife Mary was visited by her father, the Rev. William Pascoe Crook, a missionary in the Pacific islands since 1797. As the life of the Brisbane penal settlement drew to a close there was, ironically, a greater religious presence than at any time since 1824 despite the dissipating need. By this time, several German Moravian ministers, also interested in working with Aborigines, had established a missionary centre at Zion’s Hill, Nundah after their arrival in 1838. Two of them had had been ordained into the Presbyterian church by the Rev. John Dunmore Lang, who had been responsible for their recruitment, but they did not mix with the residents until the years of free settlement after 1842.

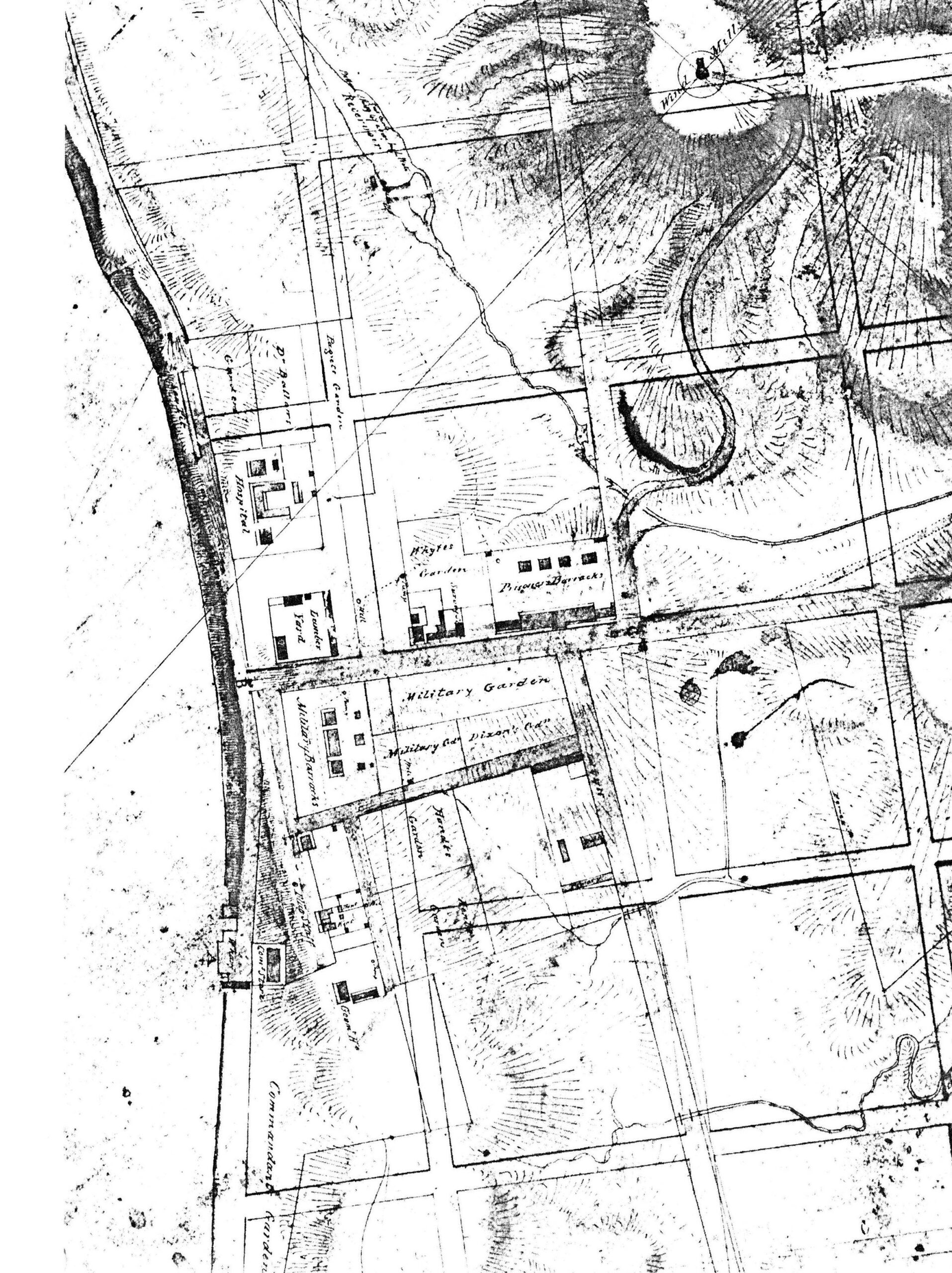

Figure 6: Plan of Brisbane Town by Robert Dixon, March 1840, showing extant buildings and proposed street grid (Steele, 'Brisbane Town in Convict Days', p. 265).

Assessing religion in early Brisbane Town

Officially at least, cleanliness of the body was equated with spotlessness of the soul, and both bathing and worship were typically reserved as a Sunday activity in Australia’s convict settlements. But little in fact was done on the spiritual side throughout the early life of Brisbane Town. The local presence of an ordained Church of England clergyman for a mere eight months during the whole of its existence emphasised the disparity between providing religious support according to the regulations and that which was offered to Moreton Bay inmates. This paucity of church-inspired comfort not only involved a total lack of appropriate ministry to Roman Catholic inmates and soldiers, but also extended to complete silence on any spiritual or sympathetic guidance offered to individuals.

One obvious reason for the failure of religious provision was that both the Anglican bishop William Broughton and his Catholic counterpart Bishop Polding (both based in Sydney) experienced ongoing problems in distributing their few priests around the ever-growing colony and Van Diemen’s Land. Many of those selected to work in New South Wales, being ill-fitted for the job, did not earn respect especially when perceived as government servants while acting as magistrates or urging compliance with officials to maintain social order. With all chaplains completely dependent on state stipends and land grants, few emancipists or convicts could discern a marked difference between their church and state roles (Grocott, 1980: 104–26). Manning Clark described them as ‘civil servants in cassocks’, while Samuel Marsden earned a doubtful reputation in Sydney by neglecting to maintain any balance. ‘He sentences the prisoner on the Saturday,’ it was said, ‘admonishes him on Sunday and flogs him on Monday’ (Clark, 1968: 107–9; Wannan, 1972: 183).

In their work amid the convicts, churchmen hoped to inspire redemption and reformation through religion while the civilian and military officers used isolation, work, and punishment to teach basic co-existence. Rarely was either solution successful. Nevertheless, clergy were an essential component in convict administration quite apart from performing traditional duties of baptisms, burials, and legal marriages. In Sydney, applications for each category of pardons, for example, required support from both a magistrate and a chaplain. Petitions for family reunifications, land grants and livestock needed similar examination and required clerical signatures, both in the colony and in home parishes. The ministers earned salaries by providing comfort to sentenced prisoners and those who required intercession with authorities at the factory and as gaol visitors.

In fulfilling these and other duties, the clergymen of convict-era Australia had a small but important role to play in governance, social order, and individual wellbeing. In the small, brutal, and highly regulated settlement at Moreton Bay, pragmatically run by local military commandants, their absence was regretted at times, but perhaps not often.

Note

Parts of this article have appeared earlier in ‘Far Separated Members of Christ’s Body’, the introductory essay to Jennifer Harrison and W. Ross Johnston (eds), The Brisbane Anglican Companion: A Dictionary of the Diocese of Brisbane 1859–2009 (Brisbane: Corporation of the Synod of the Diocese of Brisbane, 2008), and in Jennifer Harrison, “Not likely to command attention or to conciliate general esteem’: the Revd John Vincent, First Clergyman at Moreton Bay 1829’ in Marcus Harmes, Lindsay Henderson, and Gillian Colclough (eds), From Augustine to Anglicanism: The Anglican Church in Australia and Beyond (conference proceedings, 2010), and are used here with permission.

Sources and further reading

Atkins, T. 1869. Reminiscences of Twelve Years’ Residence in Tasmania and New South Wales. Malvern: The Advertiser Office.

Backhouse, J. 1838. Extracts from the Letters of James Backhouse. London: Harvey & Darton.

Backhouse, J. 1843. A Narrative of a Visit to the Australian Colonies. London: Hamilton & Adams.

Clark, C.M.H. 1968. A History of Australia, Vol. 1: From the Earliest Times to the Age of Macquarie. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

Fyans, F. (P.L. Brown, ed.) 1986. Memoirs recorded at Geelong, Victoria by Captain Foster Fyans (1790–1870). Geelong: Geelong Advertiser.

Grocott, Allan M. 1980. Convicts, Clergymen and Churches: Attitudes of convicts and ex-convicts towards the churches and clergy in New South Wales from 1788 to 1851. Sydney: Sydney University Press.

Harrison, Jennifer. 2023. Fettered Frontier: Founding the Moreton Bay Settlement 1822-1826. Brisbane: Boolarong Press and the Brisbane History Group.

Harrison, Jennifer. 2016. Shackled: Female Convicts at Moreton Bay, 1826-39. Melbourne: Anchor Books.

Harrison, Jennifer and J.G. Steele (eds). 2003. The Fell Tyrant or the Suffering Convict [by William Ross]. London: J. Ward [1836]; Brisbane: Royal Historical Society of Queensland.

King, Hazel. 1971. Richard Bourke. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Levi, John S. 2006. These are the Names: Jewish Lives in Australia, 1788–1850. Melbourne: Miegunyah Press.

O’Farrell, P. 1977. The Catholic Church and Community in Australia: A History. Melbourne: Thomas Nelson.

Oxley, D. 1996. Convict Maids: The Forced Migration of Women to Australia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rayner, K. 1962. ‘The History of the Church of England in Queensland’, unpublished PhD thesis, University of Queensland.

Steele, J. 1975. Brisbane Town in Convict Days 1824–1842. St Lucia: University of Queensland Press.

Wannan, B. 1972. Early Colonial Scandals: The Turbulent Times of Samuel Marsden. Melbourne: Landsdowne.

Related articles