Regional Chinese Temples in early Queensland

Early Chinese migrants built over thirty temples in regional Queensland, following traditional forms and techniques. The complex interiors were furnished with handcrafted carvings of immense complexity. Once a feature of many colonial and early twentieth-century towns, now only two remain, in Atherton and Innisfail.

By Gordon Grimwade

This is a 20 minute read, published June 2024.

Large numbers of Chinese migrated to Australia during the nineteenth century lured by discoveries of gold, initially in Victoria and New South Wales in the 1850s, and later in Queensland and the Northern Territory. In many parts of the north the numbers of Chinese migrants significantly outnumbered those of Europeans. For example, on the Palmer Goldfield, southwest of Cooktown, the population reached 19,500 in 1877, of which about 18,500 were Chinese immigrants (Kirkman, 1986: 49). Chinese artisans, traders, and gardeners were soon on the scene to support the miners.

The population imbalance contributed to the racist paranoia prevailing among many Europeans at the time. Despite the ironies involved, given the destruction of indigenous society by British colonialism, many Europeans were concerned the influence of Chinese migrants would lead to declining living standards and unacceptable social change inflicted by the Chinese ‘invaders’.

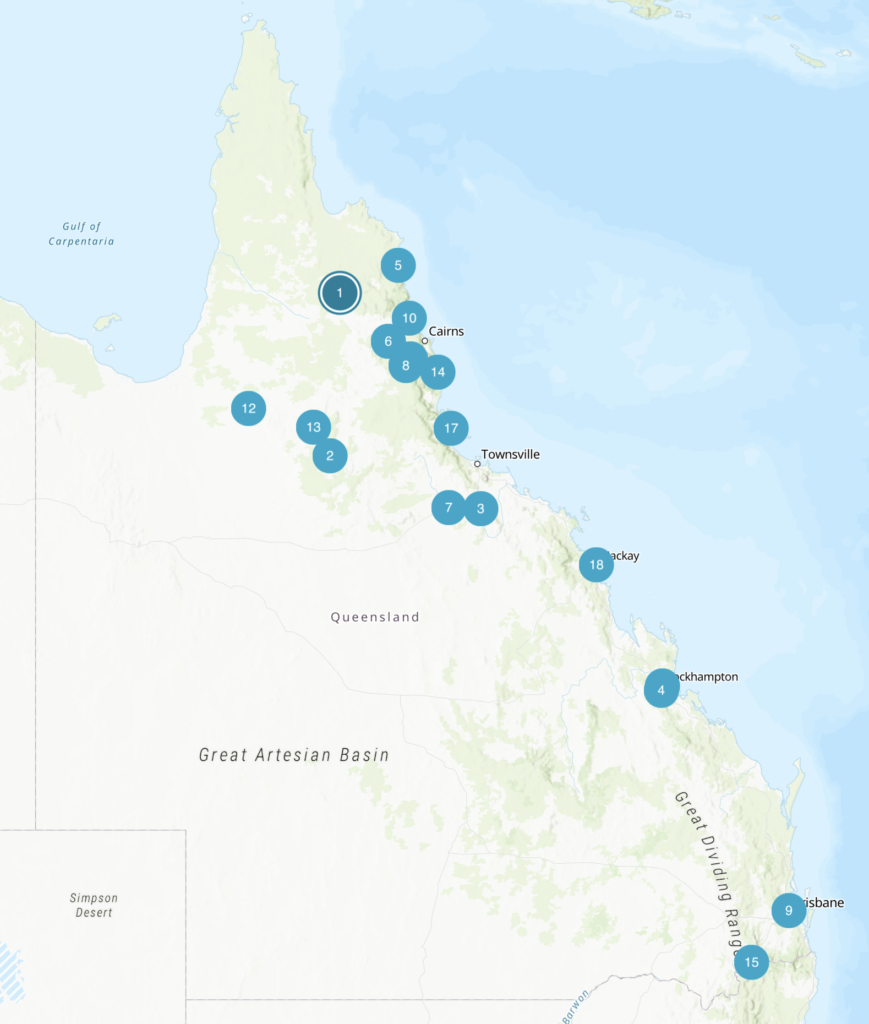

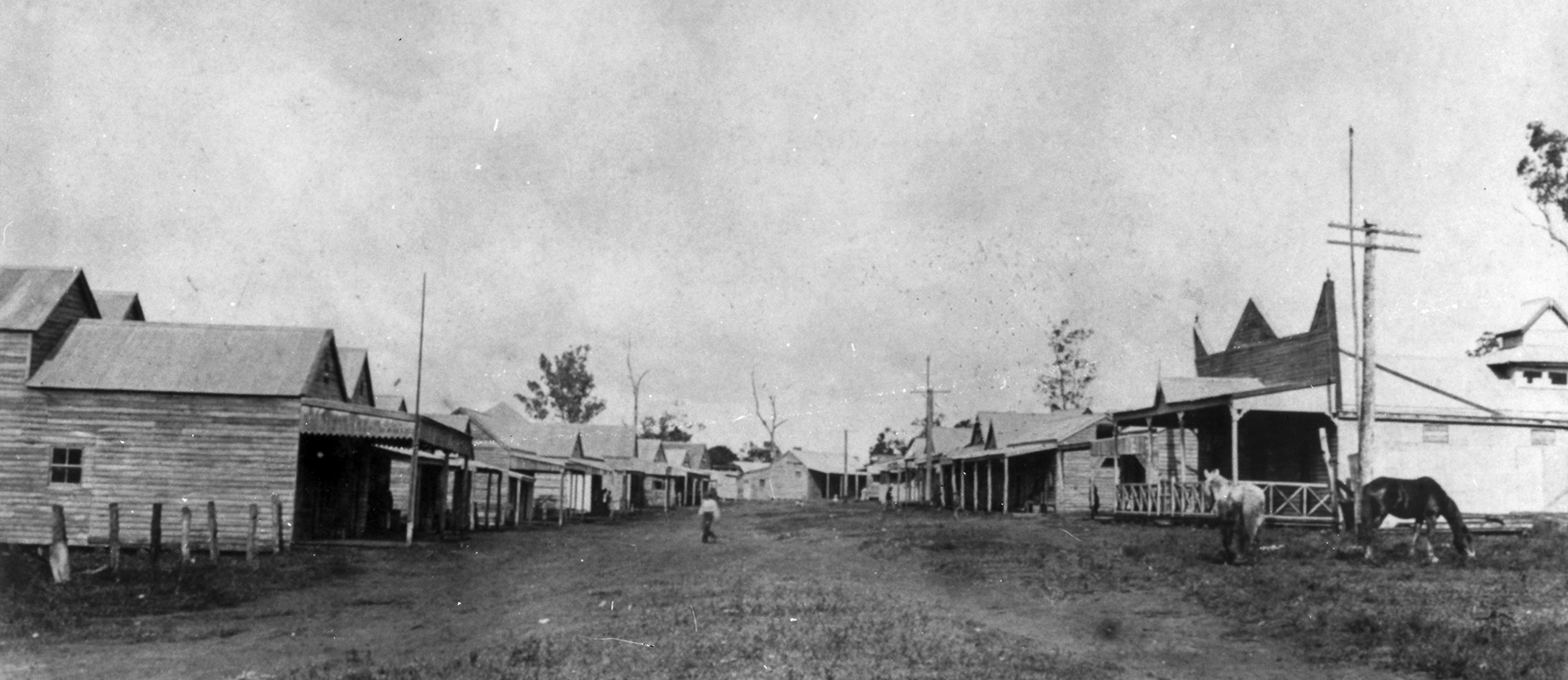

Figure 1: Chinatown, Atherton, 1912. The temple’s white fence is visible on the right side at the end of the street (National Trust of Australia).

Chinese communities, or ‘Chinatowns’, were frequently established on the fringes of European settlements, especially in Australia’s north. These largely self-sufficient, ghetto-like communities were, to varying degrees, insular enough to ensure many cultural practices were maintained with minimal disruption. Temples, often irreverently referred to as ‘joss houses’ by Europeans, were prominent landmarks in many such settlements. Population levels had to be large enough, settled and sufficiently prosperous to cover temple construction, furnishings, and on-going maintenance costs. Many smaller settlements and individual dwellings probably had temporary places of worship, but objective records are lacking.

The anti-Chinese sentiments that developed during the nineteenth century in the Australian colonies eventually materialised into what is widely referred to as the ‘White Australia Policy’. The Federation of Australia’s Immigration Restriction Act 1901, which largely halted further arrivals introduced racially discriminatory immigration measures, especially the Dictation Test, reduced the Chinese immigrant population and led to the abandonment of most Chinatowns by the 1930s. Residents had died, returned to China, or quietly melded into the wider population.

Chinese religion

Irrespective of nationality, migrants bring with them their own, diverse, cultural practices, whether these involve food, clothing, language, or religious values. European migrants were steeped in diverse Christian religious practices, Protestant or Roman Catholic, but typically other traditions were marginalised. While Jews and Muslims were variously tolerated, ignored, or castigated, Chinese religion was viewed with extreme scepticism and intolerance. There was widespread ignorance of Chinese cultural and religious practices, and the fact that temples contained statues representing an expansive pantheon of gods saw the Chinese labelled as ‘idolators’, ‘heathens’, and worse.

For their communities, the statues were tangible links between heavenly and earthly existence. While the deities they represented numbered in the hundreds, they were sometimes seen to be as fallible as humankind and could be removed from office for non-performance or raised in importance if they provided advantageous outcomes. In Charters Towers the congregation was ‘jubilant’ when their (unspecified) deity produced rain (Evening Telegraph, Charters Towers, 18 April 1902). However, in 1901 a deity in Cairns was ‘given twice round on account of his permitting the vessel containing the Chinese fireworks in New Year celebrations to run ashore on some island on the way out’ (Evening Telegraph, Sydney 15 September 1902: 5).

It is frequently claimed specific temples are either Taoist or Buddhist, or even referred to as ‘Confucian’. These three core elements — Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism, sometimes collectively referred to as san chiao, the ‘three teachings’ — are often melded with ancient ancestral worship dating back to around 1500 BCE. A single temple typically integrates two or more of these traditions, and almost always ancestor worship, such that Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, Taoist deities, and Confucian statuary and decorative homilies are often found alongside each other. Chinese religion, therefore, is often viewed as an amalgam of beliefs dating back centuries. Such processes can continue. At one stage, a small Christmas tree was placed in Atherton’s Hou Wang Temple, suggesting a capacity to also absorb Christian elements.

Belief in oracles, ancestor worship, and divination were prominent in the popular religion of nineteenth century China. In keeping with the syncretic nature of Chinese religion, a plethora of deities and powerful beings make up the Chinese cosmos. Broadly, the heavens reflect the social and political structures of earthly life experienced in the ever evolving and turbulent history of China, despite the gentler aspects invoked, particularly through Taoism.

Exemplary objects of veneration include the Yellow Emperor, Huang-Ti, who holds a particularly venerable role as the founding father of Han Chinese and, indeed, ‘the inventor of civilization’ (Stevens, 1998: 57). Beneath that exalted position exist lesser deities each with important roles to play. They include the bodhisattva, Kuan-Yin, whose origins derive from Buddhist India, and is frequently referred to as the Goddess of Mercy; and Peng Zu, one of several Taoist gods, associated with longevity (Wu Luxing, 1995). The City God, Ch’eng Huang, provides support to magistrates and has the capacity to bring rain, prevent floods, and to report mortal behaviour to the underworld gods. He reflects the syncretic nature of Chinese religion, since for many he is seen as Taoist, though he predates Taoism and his followers are strongly influenced by Buddhist and Confucian beliefs (Stevens, 1998: 171).

Queensland’s Temples

Over 130 temples were constructed by Chinese immigrants nationwide during Australia’s colonial period and into the early twentieth century, with around thirty in regional Queensland. Of those, some are consecutive constructions; for example, Innisfail has had three separate temples over the years. Two were lost to cyclones and the third, the existing temple, was not built until the 1940s. Cairns had two, losing one in a fire in 1927 and the second to decay and neglect in the 1960s.

The Hou Wang Temple in Atherton is Queensland’s only early regional temple still standing and, fortuitously, has most of its furnishings still intact. The Lit Sung Goong (Temple of All Saints, sometimes spelt Lit Shing Kung) in Innisfail, although the structure dates from 1940, has most of the original nineteenth century furnishings incorporated within. The temples at Ravenswood and Croydon have long since disappeared, but their locations remain as invaluable archaeological resources. Temple furnishings from Cairns’ Lit Sung Goong, Cooktown, Rockhampton, Georgetown (currently in Hill End NSW), Halifax (near Ingham), and Charters Towers exist to varying degrees. Knowledge about the remainder comes primarily from a few photographs and newspaper extracts which, in the latter case, need to be treated cautiously because of racial bias of the times mixed with some flamboyant journalism.

Temples came to public attention during festivities or by casual visits by writers, including the Catholic priest and geologist, Fr Julian Tenison-Woods, who described the main Cooktown temple, Lit Sung Goong, thus (Advertiser, 2 January 1880: 6):

There are two temples or joss-houses, one of which has some pretensions to architecture and ornament. Within they are very interesting. A large religious picture occupies the centre with a table in front. On this were disposed cakes, fruits, and cooked meat, with a large amount of tinsel, and tawdry, paltry ornament. Vases of incense sticks were burning at the sides. The walls were decorated with inscriptions in large Chinese characters, painted in bright colors. A good deal of bright red hangings and small banners -completed the decorations, which on the whole had rather a pleasing effect.

Most historical records provide little information of the role and form of the temple buildings themselves. For example, the Halifax temple was reported as ‘a small joss house, at the north entrance of the town, [which] gives quite an oriental effect, and serves as a reminder of the glories of the old Chinese days. There is something shabby about the joss house these days, and the local worshippers of Budha [sic] are few and poor’ (Telegraph, 8 December 1923: 13). This was written in the twilight years of Chinese migrant influences in the region when the White Australia policy was really biting. Across the nation Chinese people were being displaced and, in many cases, forced to return to their country of origin.

Writing of Bouldercombe, near Rockhampton, a reporter simply noted: ‘there was a Catholic chapel on the flat, a protestant place of worship on Church-hill, and a Joss House in the Chinese quarters but these erections have succumbed to the general ruin…’ (Capricornian, 20 October, 1877: 8).

The Killarney temple, in southeast Queensland, was completed by September 1894 and served about 200 Chinese settlers. The Queenslander (15 December 1894: 1125) reported that its main deity, whose identity was not specified, soon came under pressure because of the occurrence of excessive rain damaging the tobacco crop, for which the deity was apparently held accountable.

Temple architecture

Travellers to China, Hong Kong or Singapore will be familiar with the large, elaborate brick temples scattered across the landscape replete with ancestral halls, worship areas and walkways. With the notable exceptions of temples in Brisbane, Sydney, and Melbourne, the temples in regional Queensland were contrastingly modest timber constructions sheeted in corrugated iron or weatherboard. It is conceivable some were even timber and canvas, as has been noted in Victoria (McGregor, 2015:108).

Australasian and North American temples demonstrate significant design modifications as a predominantly male population came to grips with living and working far from their ancestral homelands. Kinship was fundamental to Chinese culture but, suddenly, those links were severed by distance, social structures had changed, skilled labour was often unavailable, and traditional raw materials hard to get.

Arguably, the structural differentiation between the capital city temples and those of regional Australia could have been due to greater affluence, larger populations, and the accessibility of a wider range of skills and materials in the capital cities. At Atherton, the front wall is timber planked but has painted rectangles across most of it to symbolise brickwork. Substitution is clearly the next best thing.

The Breakfast Creek temple in suburban Brisbane, built in 1885–86, is the oldest of the early temples remaining in the Queensland, while the Innisfail temple, built around 1940, is the youngest. Modern Buddhist and Taoist temples are markedly different in form and functionality.

Photographic and archaeological evidence indicates a notable commonality of form for the temples at Atherton, Croydon (the largest at 16.75 m x 6 m), Ravenswood, Cairns (Lit Sung Goong), and Cooktown. Robb has also identified early photographs relating to Mackay and Charters Towers which, although the quality is poor, also indicate significant similarities (Robb 2019). The current Lit Sung Goong (sometimes spelt Lit Sing Kwang) temple in Innisfail was built well after the major growth period for temple construction from around 1875 to 1910, and is distinctive with its modified Italianesque form.

Queensland’s regional temples frequently comprised two main buildings, usually of similar proportions, which were separated by a narrow walkway. One building was the actual focus for worship, while the other served as a meeting hall. In some cases, like Atherton, there were kitchens to the rear of the hall. In Australia the community-appointed caretaker often lived in part of the hall building. While many accounts refer to the caretaker as a ‘priest’, he was primarily responsible for the maintenance of the temple and ensuring items like incense and divination sticks were readily available. Regional temples were unable to either afford or justify the employment of a trained priest and relied on devout laity to fulfil many of those positions.

Temple interiors

Temple access was typically via a narrow, raised porch leading through double timber doors, with a low barrier step to deter evil spirits from entering. In Atherton’s temple a large, almost square, covered pagoda-style deck with a clerestory roof extends from the porch. Few others appear to have had similar impressive frontages (Grimwade, 1987).

Internally, a small deity stand was located to the side, on which statues of the temple caretakers and guardian of the grounds were normally placed. Immediately ahead, a second door further impeded the entry of undesirable spirits and led to a raised section — sometimes referred to as the ‘heavenly well’ — on which was placed a ding, in which incense sticks were lit. It was surrounded by a shallow depression in the floor signifying the separation of Earth and Heaven. Above this a clerestory roof allowed the incense smoke to drift unimpeded to the heavens. Croydon’s second temple set the heavenly well’s timber posts in elaborately carved and locally quarried sandstone lotus blossoms symbolising purity since they represent beauty emerging from mud (Grimwade 2003: 5, Williams 1996: 257). In most other instances more modest timber bases were used. In some instances, a support post may have been deliberately but slightly misaligned: a symbolic reference to the imperfections of humankind, for nothing in the human world can be perfect.

Beyond this area was the inner sanctuary, often taking up a little over half the building. Within it an ornately decorated deity stand was centrally positioned along the rear wall and flanked by altars and spaces for drums, cymbals, and processional banners.

Figure 7: Incense burner (ding) in the ‘heavenly well' area of Hou Wang Temple, Atherton, 2023 (Gordon Grimwade).

Deities and symbolism

Each temple had its own selection of deities. The distinctively red-faced Kuan Ti, sometimes identified as the God of War, and the Buddhist bodhisattva Kuan Yin, Goddess of Peace and Compassion, being most commonly featured. In the Cairns Lit Sung Goong Kuan Yin was, for example, a central focus. Cooktown’s Lit Sing Goong, extant between about 1878 until 1938, featured the trio of Kuan Ti, Liu Bei and Chang Fei. Legend has it that Chang Fei, a butcher, offered his entire meat supply, stored in a well, if anyone could lift the huge stone covering it. Kuan Ti succeeded in doing so but was attacked by Chang Fei who was enraged that anyone could manage such a feat. Liu Bei intervened and the three signed a pact to henceforth support each other in all their activities (Stevens 1997: 147). Atherton’s focus was on Hou Wang, the deified bodyguard commander of the last Southern Sung Emperor, who was also among those venerated in Innisfail (Kok Hu Jin, 2006: 59), while Kuan Ti is venerated in the Rockhampton’s Lit Sung Goong temple (Kok Hu Jin 2006: 75).

The iconographies of temple statues enabled worshippers to identify the deity they were approaching. With such diversity of gods, the identification of specific figures can be problematic. Even so, some features tend to stand out. Buddhist deities, for example, may incorporate a range of mudras, or hand positions. Others may hold ‘whisks’ — rods with whisps of horsehair — or inscribed tablets. The latter are often associated with statues of Confucius (K’ung Tzu).

Subtly incorporated in the numerous elaborate carved timber hangings and other décor can be found symbols often associated with Taoism, such as the yin yang, which represents duality, yin being female — Earth, moon, darkness, and absorption — and yang being male — sun, light, and penetration (Williams, 1996: 458). Within that same suite of furnishings may also be found a selection of distinctly Buddhist symbols, including the coin, endless knot, lotus, and pair of fishes. They are not mere decoration, however. The coin is an obvious expression of wealth and considered one of the ‘eight precious things’, while the endless knot, lotus, and pair of fishes are among the ‘eight auspicious symbols’ of Buddhism.

The internal furnishings in the Queensland temples were usually commissioned and imported from Guangdong province in mainland China, their acquisition reliant on benefactors whose names were frequently engraved on the artefact along with date and place of manufacture. The identification of donors in such a public style emphasises the high regard given to philanthropy, a means to generate merit in Buddhist traditions.

Examples of such artefacts include the Atherton’s temple’s clapperless bell, which dates from 1895, nine years before the temple opened in February 1904 and may, therefore, have been part of the first, short lived temple (Queenslander, 30 December 1899: 1291 and Robb, pers. com. 2023). Its counterpart in Innisfail was manufactured in late 1897, as was the carved deity stand, to coincide with the construction of its earliest temple (Kok Hu Jin, 2006: 38). The bell for Cooktown’s Lit Shing Kung was produced in 1892 by Sun Cheong Foundry with donations from the Wah On Society (Finch, 2023: 6). In Rockhampton most of the artefacts appear to have been progressively acquired between December 1899 and January 1907 although two, a timber wall hanging and a table, were added between late 1940 and early 1947 (Kok Hu Jin, 2006: 74).

The open space in the remainder of the sanctuary allowed worshippers to kneel or stand, heads bowed, to pray and offer incense sticks. Regular services were not held: worshippers came as they wished, to say prayers and make offerings, and to have their fortunes told. At preordained times, community-based celebrations and feasts associated with specific anniversaries were held.

Divination

Before undertaking important business or personal activities devotees would visit the temple to seek divine guidance (Stevens, 1997: 41). Divination or oracular blocks, most often kidney shaped with flat and curved sides, would be clutched in the hands and a short, silent question asked of the gods. The blocks are then cast on the table or even the floor. If both blocks fall with the flat side down the answer is a negative and the worshipper will put on hold any decision until a return visit when, hopefully, the outcome will be more supportive. One block up and one down is more accommodating and indicates the project or wish has the support of the heavenly world. Two blocks lying on their curved sides offers another chance, suggesting further throws might prove advantageous.

With a positive cast of the divination blocks the next step is to shake a cylinder of fortune sticks so that one of the sixty or more bamboo strips falls out. A further cast of the divination blocks is then sometimes made to ensure the right stick has been shaken from the cylinder. The numbered stick is then presented to temple staff who then interpret the fortune from the relevant, printed fortune papers.

Festivals and feasts

Temples were at the centre of the numerous festivals in the Chinese calendar, often accompanied by parades, feasting, firecrackers, drum beating, and the clashing of cymbals. Europeans, unfamiliar with such noisy celebrations, often recorded their experiences:

“John” is keeping the high festival of the new year (in Croydon), and wakes the silent watches of the night by crackers and uncouth devices of fire (Queenslander, 20 March 1880: 372).

Sachs-street (Cairns) has for the past three days been ablaze day and night with the explosion of Chinese crackers, and the air has been filled with a hideous cacophony of tom toms, cymbals and other barbaric alleged musical instruments. Europeans drawn thither by the discordancy of sounds have watched with amaze (sic) the Chinese methods of celebrating a national festival (Evening Telegraph, 15 February 1902: 2).

Impressive banquets were integral to religious festivals which included whole roast pigs cooked in large ovens in the temple grounds. Chickens were often added to the oven an hour or so before the pig was fully cooked. The results formed part of the sumptuous feasts the press often waxed lyrical about.

At the banquet itself fifty-six tables had been laid out, all of which were occupied by eight guests, making a total of 448. In addition to all this, some twenty Europeans, representing the leading men of Cairns, put in an appearance. In order to feed this multitude it was, of course, necessary to make great preparations, and we are informed that thirty cooks were employed in the holocaust of the young spring chicken and the succulent duck; while the great brick oven of the Joss House was laid under tribute in order to roast good sized pigs and other dainties on a wholesale scale (Queenslander, 22 August 1896: 347).

Oven sites at Croydon, Thornborough, and Ravenswood (two) are still evident; at Atherton a new one was constructed near the original site in 2015 and has been successfully operated several times. The Bluff Road Joss House, Charters Towers, was visited by a journalist shortly before New Year 1903 who observed cooks ‘were busy cracking nuts and others were getting the culinary utensils ready for roasting the eight pigs which formed portion of the feast to-day’ suggesting the existence of one or more ovens (Evening Telegraph, 30 January 1903: 2).

Figure 11: Aerial view of the partially collapsed ramp style pig oven at the Ravenswood temple, 2022 (Gordon Grimwade).

Loading and unloading a 90-kilogram pig required strength and a degree of stamina, and for that reason the ovens were fitted either with ramps wide enough for two men to walk with the pig suspended between them on a yoke or with a gantry crane, which would assist with lifting the pig and lowering it into the preheated oven. For those communities, lucky enough to have their ovens built into a steep bank, as with Thornborough, the cooks simply walked at ground level and lowered the carcass into the oven.

Conclusion

The practice of traditional Chinese religion in Queensland and Australia necessitated significant modifications from those experienced in China. The deep relationships that had evolved over the centuries in clan villages were absent during the colonial period, and separation from ancestral families was also associated with differing material resources, skill bases, and financial circumstances in an alien environment. Many Chinese and, indeed, European migrants, were lured to Australia to chase dreams of making their fortunes from gold mining. Few got lucky, but their firmly-held religious beliefs encouraged the development of temples — although location, appropriate fixtures, and cost were ever-present challenges. Itinerant migrants would rarely wish to invest in permanent structures when they firmly believed they would make a fortune and soon be heading back to the ancestral village.

In Queensland and its sister colonies the response was to develop a vernacular temple architecture which was, to some extent, consistent with styles adopted in North America. This adaptation highlights that most of those involved were, initially at least, sojourners and sought only to develop places of worship that were structurally sufficient to provide that essential facility in a timely manner. It was the content, not the covering, that was important, and for this reason furnishings were imported from specialist craftsmen in China.

As it became more likely that the initial, transitory existence was likely to be leading towards a more permanent residency, attention was then paid to more substantial structures and in some instances this is reflected in the serial nature of temples in some towns: Atherton and Croydon are examples. Costs were clearly an important factor as temples were only constructed in towns which provided economic stability. Gold, and the commercial opportunities it afforded, drew Chinese migrants to Australia and their strong cultural links ensured that their religious needs were met as swiftly as resources allowed.

Acknowledgements

The assistance of Ely Finch, Dr Noreen Kirkman, and Dr Sandi Robb in providing invaluable input is greatly appreciated.

Sources and further reading

Finch, E. 2023. ‘Translations of Chinese-character inscriptions on an entrance adornment, brick grave marker, tripod censer, and temple bell in the collection of the Cooktown Museum.’Unpublished report, Melbourne.

Grimwade, G. 1987. ‘Artefact layout Atherton Chinese temple, Stage 1 report.’ Unpublished report to National Trust of Queensland.

Grimwade, G. 2003. ‘Gold, gardens, temples and feasts: Croydon’s Chinese Temple.’ Australasian Historical Archaeology 21: 1–8.

Grimwade, G. 2008. ‘Crispy roast pork: using Chinese Australasian pig ovens.’ Australasian Historical Archaeology 26: 21–28.

Grimwade, G. 2023. ‘Evolving manifestations of Chinese Australian religious artefacts: a Queensland case study.’ Queensland History Journal 25.4: 298–314.

Kirkman, N. 1986. ‘Chinese Miners on the Palmer.’ Queensland History Journal 13.2: 49–62.

Kok, Hu Jin. 2006. Chinese Temples in Australia. Vol 5 Hall of the Ranking Sages in Innisfail and Hall of Martyr Heroes in Rockhampton both in Queensland. Bendigo: Golden Dragon Museum.

Luxing, Wu. 1995. 100 Chinese Gods, Singapore, Asiapac Books.

McGregor, P. 2015. ‘Joss Houses of colonial Bendigo and Victoria.’ In M. Butcher (ed.), An angel by the water: essays in honour of Dennis Reginald O’Hoy. Bendigo: Bendigo Trust, 102–22.

Robb, S. 2019. ‘North Queensland’s Chinese family landscape: 1860–1920’. PhD Thesis, James Cook University, Townsville.

Stevens K. 1997. Chinese Gods. London: Collins and Brown.

Williams, C. A. S. 1976. Outlines of Chinese Symbolism and Art Motives. New York: Dover Publications.

Related articles