Tides of change:

Torres Strait Islanders and

the Quetta Memorial Church

Since Christianity was introduced to the Torres Strait Islands as a colonial missionising effort in 1871, the receptivity of Islanders has ensured that Christian traditions have been adapted to local interests.

By Julia Mortensen

This is a 25 minute read, published June 2024.

On July 1, 2021, All Souls & St Bartholomew Quetta Memorial Church celebrated 150 years of Christianity in Torres Strait. The memorial service commenced with the blessing of the replica of the London Missionary Society (LMS) schooner Surprise by the Archdeacon of North Queensland. Congregants pressed into the pews as the Kala Lagaw Ya hymn Iesu E Master Misenare Kapten was sung to the reverberating beat of the warup. Only the formal liturgy, readings, and sermon were in English; communion was served to the Saibai hymn NgI Kai Augadh, and notices were given in Torres Strait Creole, Yumplatok. Churchgoers walked home in wait for the night-time community feast and Ailan dans performances, which, as is custom, continued into the late hours of the night.

Coming of the Light celebrations, as they have come to be known, are observed annually by Torres Strait Islander Christian communities as far south as Sydney. The Coming of Light is a cherished foundation story which is often described as the rejection of so-called ‘heathen darkness’ and the acceptance of ‘Light’ after the LMS — an inter-denominational Protestant missionary organisation — landed at Erub (Darnley Island) in July 1871. The Anglican tradition is of particular importance because the Church of England based on Thursday Island (Waibene) inherited the flocks of the LMS when it withdrew in 1915. The Quetta Memorial Church has hosted the Coming of the Light on Thursday Island since the annual celebration was established in 1919 to secure a symbolic connection with the efforts of the LMS (Beckett, 2014: 153).

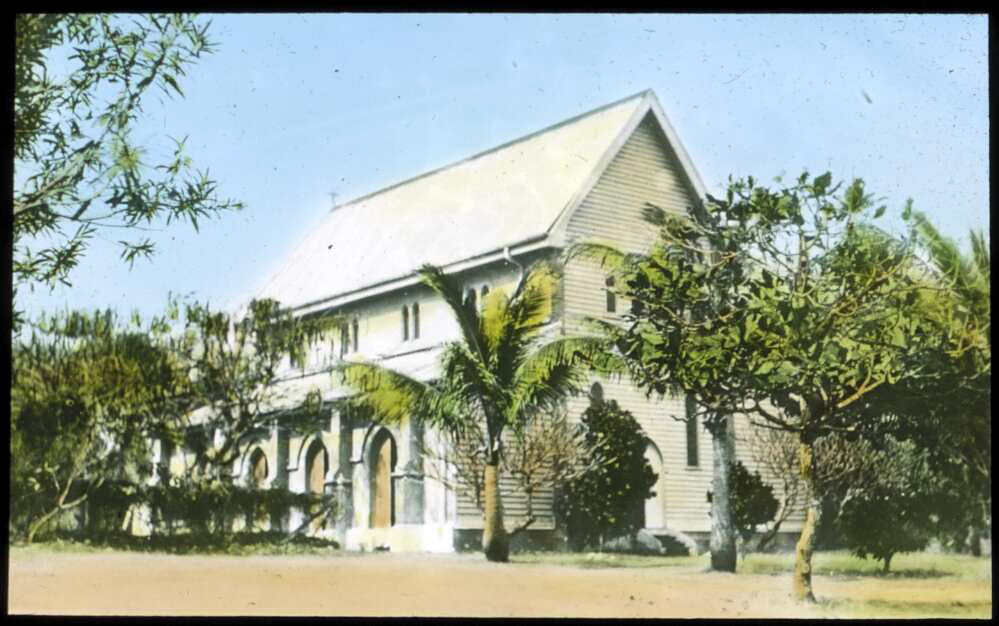

Figure 1: Quetta Memorial church, Thursday Island, c. 1930 (J. Flynn, National Library of Australia).

Formerly the Quetta All Souls Memorial Cathedral, the heritage-listed Gothic Revival church was built between 1891 and 1965. It is the central structure in the Quetta Memorial Precinct which also consists of a Bishop’s House, Rectory, and the Church Hall. Initially established by members of Thursday Island’s ruling elite as a colonial memorial to the wreck of the RMS Quetta in 1890, the church has since been transformed into an essentially Islander institution.

This was caused in part by an Anglican pastoral openness to ilan kastom. But the decisive impact of Torres Strait Islander adaptation cannot be overlooked. This inculturation materialised over the last two centuries in different forms according to government policy, and broader social and religious movements. The story of the Precinct illustrates the broader story of Torres Strait Anglicanism.

Establishing the Quetta Memorial Precinct

When the Quetta Memorial Precinct was established in the late nineteenth century, it was built as a colonial memorial to the Quetta shipwreck for the use of the Island’s ruling class. Although Thursday Island was a rich ‘poly-ethnic’ town, it remained a stratified society. Traditionally owned by the Aboriginal seafaring Kaurareg people, the Island was not permanently inhabited until it was established as a strategic government outpost in 1877 to guard what had become an important trade route linking the Pacific and Indian oceans (Osmond, 2021: 4). After Government Resident John Douglas, a former Premier of Queensland, opened the island to private settlement in 1885, thousands of immigrants from Asia and the South Pacific came to work in the various marine industries, while few Indigenous people were permitted to reside on the Island (Osmond, 2021: 4). What emerged was a socioeconomic hierarchy grounded in Social Darwinism and capital. Europeans were thus at the pinnacle of industry, commerce, government, the military, and, of course, religion. The first three government residents were said to be ‘devout communicants of the Church of England’ (White, 1917: 43). The rest of the population were distributed according to colour, government policy, and the marine industry, with Aboriginal people and Pacific Islanders (a contemporary collective term which included Torres Strait Islanders) at the bottom (Beckett, 1987: 58). It was under these circumstances that the Precinct was established by the Island’s ruling elite as a ‘fitting memorial’ to the colonial tragedy of the Quetta (Quetta Memorial Committee, 1895: 4).

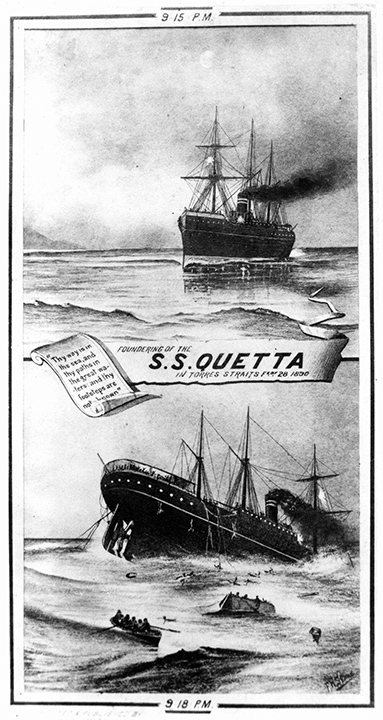

As one of Queensland’s deadliest maritime disasters in the unruly seas of the remote north, the sinking of the Quetta became a symbol of colonial life in the tropics. The British Indian mail steamer was outbound from Brisbane to London when it collided with an unchartered rock in the Adolphus Channel not far from Thursday Island on February 28, 1890. Despite clear skies and low winds, she sank in three minutes after the rock tore the ship’s hull (Singe 1989: 93). The Quetta’s sinking killed between 133 and 173 of the 292 passengers and crew, including most of the Europeans on board. Public feeling over the loss of the Quetta was strong. Amongst the dead were Alexander Archer, manager of the Bank of New South Wales in Brisbane, and his wife, Mary Louisa, daughter of former Queensland premier Sir Robert Mackenzie (Morning Bulletin, 1890: 5). News of the tragedy particularly affected the Thursday Island community, not only for its proximity, but because many residents preferred the comfort and reliability of the mail steamer to return after the wet season. They too lost their lives in the shipwreck (Singe 1989: 92).

Visiting Church of England New Guinea missionary A.A. MacLaren read a ‘very beautiful and touching’ burial service over the scene of the ‘terrible wreck’ and was struck by the need for ministry in the wake of the disaster (Bayton, 1965: 65–67). At a Thursday Island Church of England Committee meeting held on April 10, 1890, MacLaren proposed a subscription to raise funds for the erection of a church as a memorial to those lost in the Quetta, sending out the request publicly in The Brisbane Courier later that month (1890: 6). In July, the Bishop of North Queensland George Stanton resolved that ‘a Church and a Parsonage be erected on Thursday Island’ and a committee was subsequently established to carry this into effect (Quetta Memorial Church Committee, 1895: 4). Earlier progress had foundered after the Douglas Street site was purchased for the Church of England in 1885 (The Church Chronicle, 1904: 5). Services were held in the meantime at the courthouse by lay preachers and visiting clergy. With MacLaren’s call for subscriptions and the collective loss felt across the colony, the opportunity had now arisen to raise enough funds to establish their long-awaited church.

The immediate need was to provide for a resident clergyman. Between 1890 and 1891, a parsonage for the incumbent Reverend Maitland Woods was built with locally raised subscriptions. At the same time, canvassing commenced for the construction of a memorial church, with an estimated cost of £3,000 to cover what was envisioned to be durable, artistic and ‘worthy of its commemorative intentions’. The appeal for funds across Australia and the ‘Mother Country’ raised a partial sum of £1,598/7/2 (Quetta Memorial Committee, 1895: 5). Designs for the church were obtained from the architect for the Diocese of Brisbane, J.H. Buckeridge. As was fashionable in the late-nineteenth century, the Quetta Memorial Church was designed in Gothic Revival style, with structural distinctions between nave and chancel, steeply pitched gabled roofs, and arched windows and doors (Andresen, 1998: 5.05). The foundation stone was laid by John Douglas on May 24, 1893 (Bayton, 1965: 67–68). Certain concessions were made for local conditions, including the use of concrete rather than stone or brick. Extra ventilation was added both to the original design and to later additions, including the 1965 front extension designed by Reverend John Bayton (Daunt, 2021: 519–30).

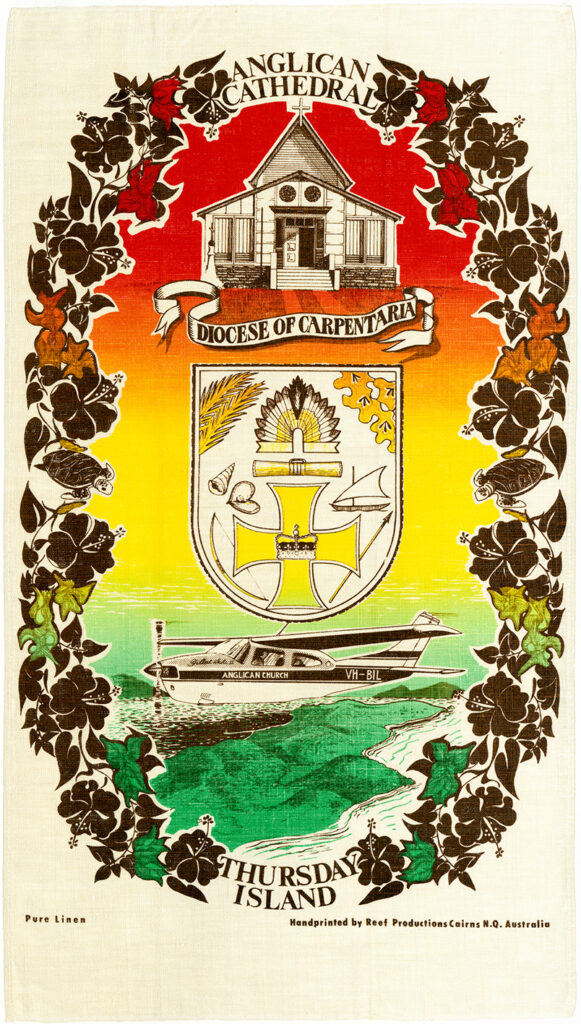

The humble yet grand architectural design of the church became even more fitting when Thursday Island was chosen as the centre of the newly formed Diocese of Carpentaria in 1900, which was re-absorbed into the Diocese of North Queensland in 1996 (Quetta Memorial Cathedral Committee, 1989; Mullins, 2001: 23). In contrast, the Church Hall (also known as the Parish Institute) built between 1902 and 1903 is a simple rectangular timber-framed building with a high gabled corrugated roof prioritising practicality above aesthetics. Both the Bishop’s House (1891), situated behind the Church Hall, and the Rectory (1904) are two of the oldest standing residences on the Island.

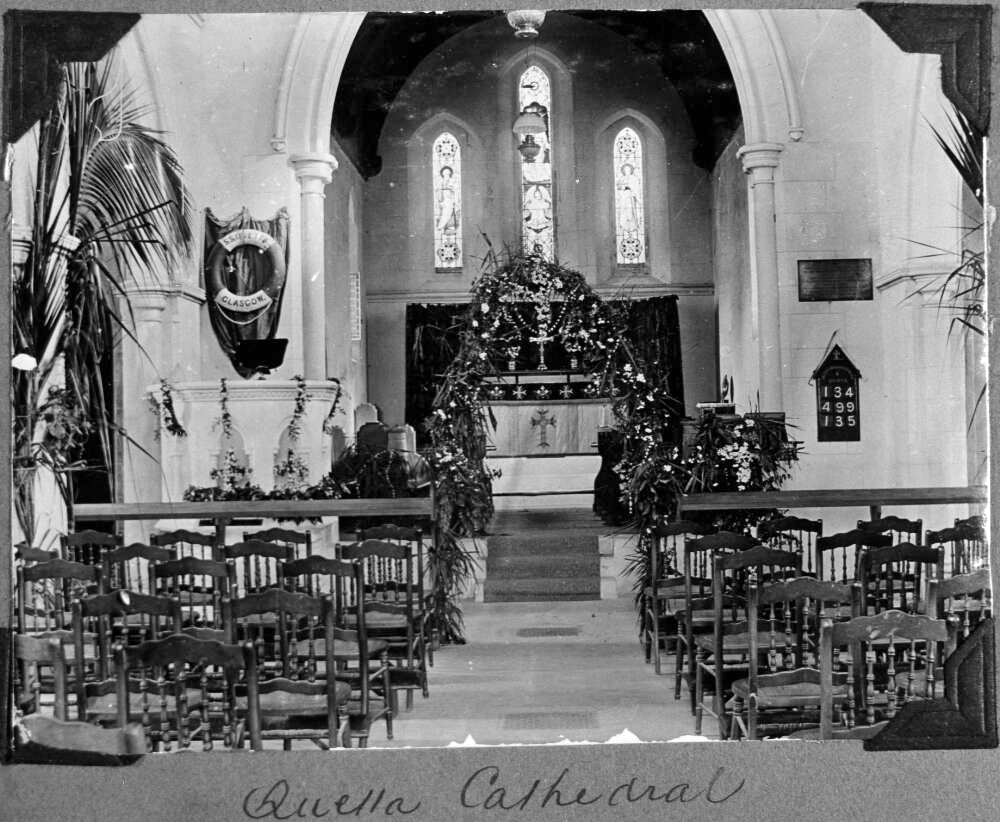

Reputed to be the only memorial church in Queensland for a maritime disaster, the former cathedral is brimming with relics from the dangers of the deep. There are numerous artefacts salvaged from the Quetta including the ship’s bell, engraved ‘Quetta 1881’, a lifebuoy, a porthole encrusted with marine growth, and a teak slab from the wheelhouse. The marble top on the high altar was from the steamer’s saloon bar. Many of the furnishings and plaques were donated to the church by passengers’ families. These include a window in memory of Alexander and Louisa Archer. Besides those recovered from the Quetta, many of the relics and memorials inside the church reflect its colonial beginnings. A memorial plaque to those who perished in the Cape Melville disaster of 1899 — where 73 vessels were sunk or damaged by Cyclone Mahina — names the European men who drowned, while the ‘295 coloured men’ who lost their lives are unidentified. Hung along the eastern aisle is the Union Jack lowered at the Island’s Green Hill Fort in 1901 at the proclamation of federation. As an almost colonial trope, this was the backdrop of the vibrant cultural convergence occurring within and around the walls of the cathedral.

Figure 4: Quetta Cathedral, Thursday Island, Queensland, Douglas family collection, 1913 (National Library of Australia).

Torres Strait Anglicanism

Centuries of both violent and peaceful interaction with outside cultures — as a pre-colonial thoroughfare for Papuan and Aboriginal traders, followed by Spanish and Portuguese explorers, and later as an Imperial shipping route — ensured that the loose groupings of islands in Torres Strait were familiar with outsiders. What developed was an intrinsic openness to other cultures. As the anthropologist Anna Shnukal has observed, ‘Islander custom and language were apparently always syncretic, receptive to difference and outside influence and eager to accept and transform them’ (2004: 111–12). As we will see, the response to the Church of England was no different.

After the LMS withdrew from Torres Strait in 1914 to focus on its efforts in Papua, and formally ceded its churches to the Church of England in 1915, the Quetta Memorial Cathedral became the focus of religious life in Torres Strait. Unique to churches established in Indigenous communities across Australia, the parish was not established for missionary work. While the diocese was affiliated with the Australian Board of Missions, its intended purpose was to serve the rapid influx of Europeans to Torres Strait in the late nineteenth century (Wetherell, 1993: 5–6). The Anglicans had therefore limited their activities to the religious sphere and by-and-large continued to allow non-Europeans to interact with the church and its religion as they pleased.

Certainly, the task of conversion had already been completed by the LMS, but the Anglicans came to reject the Society’s ‘civilising mission’. Under the LMS, cultural practices such as sorcery, headhunting, polygamy and the use of fetishes were prohibited, strict Sabbatarianism was enforced, ‘licentious’ dancing was forbidden and the use of the warup was banned. W.H. MacFarlane, a priest who served the Anglican diocese in the early twentieth century, described how this policy was reversed (albeit after practices most abhorrent to Victorian sensibilities had been suppressed):

There was sometimes too much of the idea of requiring the new converts to abjure that which was not actually out of harmony with Christian precepts… Our policy was to ‘christianise’ old customs where possible, and to retain native forms of expression (rather than so called ‘white man custom’) instead of arbitrarily cutting out everything (1959 in Beckett, 1987: 80).

Christian socialism, an ideology popular within the Church of England in the early twentieth century, was sympathetic to the ‘noble’ pre-capitalist cultures of Torres Strait. The longest-serving Bishop of Carpentaria, Stephen Davies (1922–49), who had overseen the establishment of the Lockhart River Co-operative and the Moa Fishing Company, was described by his family as ‘a socialist’ (Wetherell, 2001: 208–9). The continued practice of traditional custom was therefore encouraged by church leadership.

Figure 5: Yorke Islanders leading Jubilee celebrations on Thursday Island, 1927 (State Library of Queensland).

After Torres Strait Islanders were permitted to reside on Thursday Island following World War II, Island hymns alternated with Hymns Ancient and Modern, and the organ was replaced by the warup. Readings were in both English and the vernacular. On ecclesiastical and cultural occasions, the church grounds were opened for feasting and dancing. Tombstone openings (a modernisation of traditional mortuary rites) emerged with full patronage and participation, performed on consecrated ground with an officiating priest. Dress was also markedly Islander. Congregants went barefoot, men in lava lava and women wearing brightly coloured hibiscus-print dresses. The first Islander priests were said to have preferred ‘calico and a singlet’ to the ‘dog collar’ (The Queenslander, 1926: 16). Congregants from the remaining white congregation did not like these developments and many withdrew. By 1958 the majority of the laity was Torres Strait Islander (Beckett, 1987: 156–60). On the surface, the Quetta Memorial Cathedral was an Islander institution.

Nevertheless, perceptions of race still determined relationships between the church and its adherents. In 1917, Bishop Gilbert White described Islanders as ‘perpetual children’ who required spiritual guidance (White, 1917: 54). The practice of calling white priests baba (father) and their wives ama (mother) was starkly contrasted by the Islander priests who were referred to by their given names (Beckett, 1987: 97). The Reverends Joseph Lui and Poey Passi, the first Torres Strait Islanders to take Holy Orders in the Church of England, were ordained as deacons at the Quetta Memorial Cathedral in 1919. By 1940, the Bishop of Carpentaria had ordained another six Indigenous priests. The priests had been trained at St Paul’s Island (Moa) Theological College, which had a poor reputation — one white priest described them to the anthropologist Jeremy Beckett as ‘good chantry priests’ (2014: 159). Though they were recognised as leaders of the church, they were still Indigenous men who were living under the Queensland Protection Acts. Commonly referred to as ‘the dog Act’, Torres Strait Islanders became subject to the Queensland Protection Acts in 1904 after the death of John Douglas. These protectionist policies, which began in the colony in 1897 and continued into the 1970s, controlled the minute details of Indigenous peoples’ lives. Due to the Islanders’ separate racial status, inconsistently recognised by government policy, they were not systematically removed and dispossessed as on the mainland. Instead, movements were restricted to certain islands, strict surveillance was imposed, and local people diminished, their wages, employment and relationships controlled by the state (Nakata 2007: 130).

Torres Strait Islanders destabilised this paternalistic control by bridging the gap between traditional spirituality and Christianity. Both Joseph Lui and Poey Passi were said to ‘negate Darkness by carrying the power of God into domains of which Europeans were ignorant or uncomprehending’ by combining Christian belief with sorcery (Beckett, 1987: 98). When one was teased for his chastity by a group of teenagers talking about love magic, he was said to have responded: “Alright, I’ll match my puripuri [magic] against yours — inside the church” (Beckett 1987: 98). This was also practiced by churchgoers on Thursday Island. According to Willie Wigness, a Kaurareg elder and church councillor, ‘when religion came’ traditional spiritual practice was maintained quietly, ‘out of sight, out of mind, to keep it alive’ alongside their Christian faith (2023). These quiet subversions alongside outward practices of ‘acceptable’ forms of culture such as dance and song characterised the Protectionist era of Torres Strait Anglicanism.

Division and unity in the modern era

The second half of the twentieth century brought significant upheaval to the Quetta Memorial Cathedral and Anglicanism in Torres Strait more broadly. Across Australia, the Indigenous self-determination movement was gaining traction in the late 1960s. In Torres Strait, emphasis was placed upon political independence and administrative autonomy — with secession first seriously proposed by the Torres United Party (TUP), founded in 1976 by James Akee and others after Papua New Guinea was granted independence in 1975. This gained further momentum in the 1990s when the Mabo case, which established the traditional land ownership of Mer (Murray Island), led the High Court of Australia to confirm the continued existence of native title for the whole of Australia (Wetherell, 2001: 211–13). Religion played a strong symbolic role during this period as a desire to break from the established order (still seen to be aligned with the Anglican Church) existed alongside the conservative traditionalist movement. These competing interests saw many Islanders convert to Pentecostalism or shift to High Anglicanism. As the administrative centre of the region, the Quetta Memorial Precinct was oftentimes the stage upon which these events unfolded.

The 1960s ended the near monopoly of Islanders’ allegiance to the Church of England. Collapse of the marine industries, and the introduction of the less restrictive 1965 Aborigines and Torres Strait Islander Affairs Act (Qld), saw mass migration of Islander men to the mainland to work in sugarcane cutting and in railway gangs. Compared with Torres Strait Anglicanism, many Islanders found mainland churches unfamiliar and unwelcoming. Several converted to Pentecostal groups, especially the Assemblies of God, which openly welcomed their ‘brothers and sisters’ and invoked the ‘fiery spirit’ of the Congregationalist-leaning LMS (Mullins, 2001: 21).

Pentecostalism was taken back to the islands where it was viewed as more attuned to the modern world than the decorum of the Anglican liturgy. Pentecostals wore western clothes to church, the guitar replaced the warup, and hymns were sung in English. Island dancing was prohibited. While this appears at odds with the cultural renaissance occurring at the time, Pentecostalism became the religion of political dissent as it aligned itself with the forward-thinking independence movement. Others filtered into the Uniting Church, while some became adherents to the Jehovah’s Witnesses and Seventh Day Adventists (Mullins, 2001: 25).

Believing that a Torres Strait Islander leader would overcome mounting dissatisfaction, the Diocese of Carpentaria created the position of Assistant Bishop in 1984. Kiwami Dai of Saibai Island was the first to be appointed in 1984 until his retirement in 1992. In 1995, a management consultation commissioned by the Diocese of Carpentaria recommended that they should return to the Diocese of North Queensland. In contrast to the regional push for autonomy, it was believed that there were not enough financial or human resources to continue to support the Far North Queensland diocese. A concession was made that the future of Torres Strait Anglicanism required that ‘an indigenous Person be chosen as Bishop of this region’ as this was ‘the expectation of the Torres Strait Islander people at this time’. It was hoped that this would be a source of unity leading those who had strayed ‘back into the Mother Church’. As part of merger negotiations, a provision was made for a regional Bishop of Torres Strait, who would reside on Thursday Island, and a Torres Strait Regional Council (TSRC), which would have authority for regional administration. The bishop would be recommended to the Bishop of North Queensland by the ‘clergy and laity of the Torres Strait region, according to Torres Strait culture and custom’ (Wetherell, 2001: 201–2).

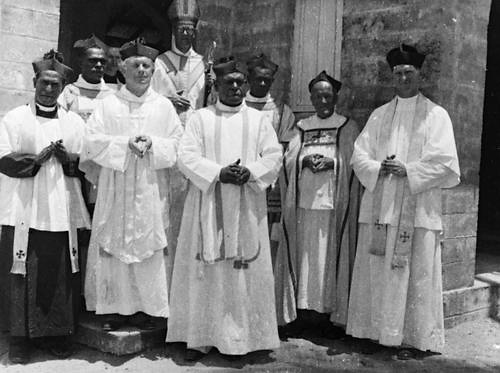

Figure 7: Anglican clergy in the Torres Strait, 1954 (photographer W. Reichnitz, State Library of Queensland).

The hopes that some autonomy might be salvaged were dashed when Bishop Clyde Wood of North Queensland chose Morrison Ted Mosby. Though an ordained Anglican priest, Mosby had become associated with the Full Gospel Church. He withdrew his candidacy as most of the nominees were more senior. Mosby’s candidacy was reinstated and he was consecrated at the Quetta Memorial church in September 1997. In a society which deeply respects elders and tradition, the appointment of a younger Pentecostal sympathist was incendiary (Mullins, 2001: 25). Torres Strait Anglicans felt betrayed. ‘We feel our culture, our church history, the importance to us of our faith and the importance of the office of bishop, not only to Anglicans but to all Torres Strait Islanders has been ignored,’ wrote Gayai Hankin (1997), a dissident and protégé of the ‘old’ Islander priests. A petition was subsequently signed by ‘hundreds’ of Thursday Islanders asking for Mosby’s removal. The TSRC accepted a motion of ‘no confidence’ in Bishop Wood’s leadership and Islander clergy walked out of talks where it became clear Wood would stand by his decision (Wetherell, 2001: 203–4).

The crisis over the choice of bishop led 16 of 18 active Islander churches to begin talks with the Traditional Anglican Communion (TAC). Dissatisfaction was mounting amongst the staunchly traditional Torres Strait Anglican community, which opposed female priests and new liturgies accepted by the Anglican Church of Australia in the 1990s (Wetherell, 2001: 201-3). A schism was inevitable. In December 1997, the TSRC seceded from the Anglican Church of Australia to form the Church of Torres Strait (CTS). The newly formed Church combined traditional belief systems — viewing itself as continuing the Malu-Bomai cult of Mer — with a return to ‘Anglo-Catholicism’, reverting to the 1662 prayer book (despite Anglo-Catholics’ traditional antipathy to it), and adopting terms such as ‘Father’ and ‘Mass’ (Mullins, 2001: 26). Gayai Hankin was consecrated on Thursday Island as the first bishop of the CTS. Hankin led another breakaway in the early 2000s, establishing The Independent Church of Torres Strait and Kaiwalagal Inc. Indigenous leadership had asserted its regional autonomy on the public stage, creating a religion independent from white decision makers and their institutions.

Recovery from the schism was slow. The fracturing caused many families to retreat into their clan groups and splinter into smaller denominations. It is only within the last decade or so that the parish has forged a new path under the umbrella of shared heritage. Returning to the 150-year anniversary of the Coming of the Light, the 2021 memorial event was a combined service which purposefully brought together the various denominations across the Island. Held at the Quetta Memorial church, the masthead of Anglicanism in Torres Strait, readings were given by members from the Australian Christian Church (the renamed Assemblies of God), the Uniting Church, and the Catholic Church. Thanks was given for the support proffered by the same denominations, as well as the Seventh Day Adventists and the CTS. The event was intended to bring families back together based on shared historical connection to the Anglican Church, as explained by Church Warden, Aunty Pauline Ah Wang ‘when they need family, they come back to the main church,’ which she also described as ‘the mother house of the people of Torres Strait’ due to its ancestral and cultural connections (2023). Willie Wigness, similarly understands the Quetta Memorial Church ‘as the big church of the Torres Strait’ as it is where his ‘mother and father… [and] their mother and father’ came from (2023). Though the Coming of the Light is now contentious because of its colonial implications, it remains the foundation story of Christianity in the region. Members of the Quetta Memorial Church have therefore actively attempted to unite the divided Christians of Torres Strait by appealing to their historically minded culture. As Epraim Bani, a Mabuiag elder who rose to prominence as an intellectual in the 1970s, is known to have said, the ‘Past must exist for Present to create the Future’ (Bani in Roy, 2011: 12).

Further attempts at reconciliation have been made, this time for the institution’s own colonial past. Recognising that religion was used to control his people, Willie Wigness says that current leadership are focused on ‘supporting that evangelism out there’, moving into an autonomous, unified future founded in faith (2023). A memorial stone listing all the men who lost their lives in the Cape Melville disaster was unveiled on the cyclone’s anniversary in 2023. Six plaques, listing the nearly 300 men who died in the disaster, are displayed on a memorial stone in church grounds. The memorial also pays tribute to the non-European lives lost on the Quetta. As it stands today, the Quetta Memorial Precinct is an Islander institution with a colonial past which lingers on its walls and in its archives. Under Indigenous leadership, in an attempt to unify the divided Christian Torres Strait community, it is finally coming to terms with this origin story in typical Torres Strait Islander fashion — through a simultaneous assertion of heritage and autonomy. In this way, the Quetta Memorial church has been the site of modern adaptations of culture and reconciliation, echoing the broader themes of Torres Strait Anglicanism into the modern era.

Conclusion

The Quetta Memorial Precinct illustrates how a colonial edifice, with all the symbolic bells and whistles of Empire, became a Torres Strait Islander institution. While recognising that this was encouraged by Church of England clergy, deeper analysis has revealed that Islander peoples were active participants in this transformation in the changing tides of Torres Strait Anglicanism. After Torres Strait Islander peoples, whose Christian congregations were inherited by the Anglicans through the LMS, were routinely permitted to reside on the former government outpost, they quickly displayed characteristic syncretism by practising ‘acceptable’ elements of ilan kastom, such as hymns in the vernacular, Island-style dress, and dance. Spiritualisms, which were less appreciated by the Anglican leadership, were quietly (yet significantly) retained by Islander clergy and laity. The politically charged self-determination era saw the end of the Anglican Church’s monopoly, which eventually led to the expression of dissatisfaction and independence with the secession of the CTS in 1997. While faith remains divided on Thursday Island, local church leaders have recently encouraged unity by emphasising a sense of the shared ancestral connection with Anglicanism. It remains to be seen what the future will bring for the Quetta Memorial Precinct, though current local leadership appears to be following Ephraim Bani’s words by coming to terms with the institution’s past to move into the future.

Sources and Further Reading

Secondary sources

Andresen, B. 1998. Church register: an inventory of parish churches within the Diocese of Brisbane 1847 to 1903, a conservation study prepared for The Diocese of Brisbane Anglican Church of Australia. Brisbane: Department of Architecture, University of Queensland.

Bayton, J. 1965. Cross over Carpentaria: being a History of the Church of England in Northern Australia, From 1865-1965. Brisbane: W.R. Smith & Paterson, 1965.

Beckett, J. 1987. Torres Strait Islanders: custom and colonialism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Beckett, J. 2014. Encounters with Indigineity: Writing about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies.

Daunt, L.M. 2021. ‘Tradition and Modern Ideas: Building Post-war Cathedrals in Queensland and Adjoining Territories.’ In Ultra: Positions and Polarities beyond Crisis, Proceedings of the 38th Annual Conference of the Society of Architectural Historians Australia and New Zealand, Adelaide.

Mullins, S. 1994. Torres Strait: a history of colonial occupation and culture contact 1864-1897. Rockhampton: Central Queensland University Press.

Mullins, S. 2001. ‘Kastom, Syncretism and Self-Determination: the Reconciliation of Bipotaim and Pastaim in the Church of Torres Strait.’ Queensland Review 8, 1: 21–30.

Nakata, M. 2007. Disciplining the Savages: Savaging the Disciplines. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press.

Osmond, G. 2021. ‘Bending the Ball: Racial Policy and 1930s Sport on Thursday Island.’ Australian Historical Studies 52: 1–21.

Queensland Heritage Register. 2001. ‘Quetta Memorial Precinct,’ accessed 7 February 2023, https://apps.des.qld.gov.au/heritage-register/detail/?id=602168.

Shnukal, A. 2004. ‘Language diversity, pan-Islander identity and ‘national’ identity in Torres Strait.’ In Davis, R. (ed), Woven histories, dancing lives: Torres Strait Islander identity, culture and history. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press, 107–23.

Singe, J. 1989. The Torres Strait: people and history. St Lucia: University of Queensland Press.

Wetherell, D. 1993. ‘From Samuel McFarlane to Stephen Davies: continuity and change in the Torres Strait Island churches, 1871-1949.’ Pacific Studies 16, 1: 1–32.

Wetherell, D. 2001. ‘Whatever Happened in Torres Strait?: Interpreting the Anglican split of 1998.’ The Journal of Pacific History 36, 2: 201–214.

Primary sources

Aborigines and Torres Strait Islander Affairs Act 1965 (Qld). https://www.legislation.qld.gov.au/view/pdf/asmade/act-1965-027.

Hankin, G. 1997. ‘Ad Clerum: The Clergy of the Diocese of North Queensland.’ In Wetherell, D. 2001. ‘Whatever Happened in Torres Strait?: Interpreting the Anglican split of 1998.’ The Journal of Pacific History 36, 2: 204.

‘Ordination of Island Priests.’ 1926. The Queenslander, 16 January: 16.

‘Proposed Quetta Memorial Church.’ 1890. The Brisbane Courier, 22 April: 6.

Quetta Memorial Church Committee. 1895. ‘Quetta Memorial Church’. Anglican Diocese of Far North Queensland archives, File 8583.

Quetta Memorial Cathedral Committee. 1989. ‘The Cathedral Church’. Thursday Island: Torres News.

Roy, M. 2011. ‘Adhi Ephraim Bani Tombstone Unveiling.’ Torres News, 19 October: 12.

‘The late Mr. Alexander Archer.’ 1890. Morning Bulletin (Rockhampton), 12 May: 5.

White, G. 1917. Round About the Torres Straits: A Record of Australian Church Missions. London: Central Board of Missions.

Related articles