Queensland's Theravada Buddhist Temples

Theravada Buddhism is found predominantly in Sri Lanka and the Southeast Asian nations of Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia. People from these and other countries have established distinctive local centres for Buddhist life throughout southeast Queensland.

By Patrick Jory

This is an 18 minute read, published June 2024

This essay discusses the history of the establishment and growth of Theravada Buddhism in Queensland. We consider the importance of the different national traditions — the Sinhalese, Lao, Cambodian, Burmese and Thai; the range of religious, spiritual, and cultural services offered by the various Theravada Buddhist temples; the relationship between these temples and the local Queensland community; and the close links between Queensland’s Theravada Buddhists and temples in Southeast Asia and in other parts of the world.

Everyday Theravada Buddhist Practice

For many Theravada Buddhists the most common religious activity is to ‘make merit’ — literally to do good deeds. Making merit is based on the belief that good deeds will be rewarded in a future incarnation. The typical merit-making activity is to offer food to the monks. In Theravada Buddhist countries monks will walk out from their temples in villages, towns, and cities in the early morning with alms bowls into which the lay Buddhist community will present food. In Australia, this everyday ritual is not possible, so lay people will come to the temples each morning to offer food to monks residing in them.

Other forms of merit-making include offering monastic robes to the monks and funds to cover the expenses of running the temple. At someone’s death family and friends of the deceased invite monks to perform merit-making rituals to enable the spirit of the deceased to have a better rebirth.

There are a number of major merit-making festivals in the Theravada Buddhist calendar, including Magha Puja, in February or March, which commemorates the Buddha’s teaching of the monastic rules (Patimokkha); the Buddhist New Year in mid-April; the Visakha (or ‘Vesak’) festival, usually held in May, which commemorates the birth, enlightenment, and the passing away or parinibbana of the Buddha; the commencement of the Rains Retreat, from July to September, when monks are confined to their temples; and the Kathina Robe-Offering Ceremony, which usually takes place in October or November.

Theravada Buddhism’s Origins in Queensland

There is some evidence that the first attempt to establish a Theravada Buddhist community in Queensland took place in the 1870s, among a group of Sinhalese who had come to far north Queensland to work in the sugarcane plantations and in pearl diving. The renowned Sinhalese Buddhist reformer, Anagarika Dharmapala (1864–1933), claimed that a small Buddhist temple including a Bodhi tree once existed on Thursday Island, however the temple has not survived (Sarath-Chandra, 2013; Croucher, 1989: 5).

From the 1980s, the number of Theravada Buddhists in Queensland multiplies, largely as a result of the end of the White Australia policy a decade earlier and the subsequent increase in Asian migration to Australia. This initially came about due to an intake of refugees from the conflicts in Indochina (particularly in the case of Lao and Cambodian migrants), and later in the early 1990s through the expansion of Australia’s migrant intake. An increase in international students from Southeast Asia, especially Thailand, has also contributed to the growth of the Theravada Buddhist community in Queensland.

A second key factor conducive to the growth of Theravada Buddhism in Queensland has been Commonwealth and State government support for multiculturalism, including the religious practices of Australia’s increasingly diverse population. For example, government approval is required for the registering of religious associations and establishment of temples, the approval of building permits, and the issuing of visas for ‘religious workers’.

Third, Theravada Buddhist communities have been active in setting up organizations to promote religious activities. In 1981 a Queensland Sangha Trust (QST) was established with representatives from the different Theravada communities to promote the development of Theravada Buddhism in Queensland. The following year the first Theravada Buddhist temple was founded in Brisbane, the Brisbane Buddhist Vihara Inc., in Highgate Hill. Over time, the importance of language differences and the strength of national traditions among the different Theravada communities became more widely acknowledged. The QST moved to support the establishment of temples for each of the major Theravada Buddhist communities — the Sinhalese, Burmese, Lao, Cambodian, and Thai (Sarath-Chandra, 2013). A key source of support for the establishment of these temples came from already established temples in Sydney and Melbourne, which provided advice and sometime even sent monks as pioneers to set up temples in Queensland.

Theravada Buddhist temples can be found as far as Rockhampton, Townsville, and Cairns. However, the majority are in South East Queensland. In 2023 there were twelve Theravada Buddhist temples located in Brisbane, Logan, Gold Coast and Sunshine Coast.

The first of the Southeast Asian Theravada Buddhist temples founded in Queensland was the Lao temple in Bellbird Park, Ipswich, in 1990. A Cambodian temple followed in Waterford, Logan City, in the same year. The first Thai temple, Wat Thai Buddharam, was established in 1991 in Ellen Grove, later moving to its current Forestdale location due to the construction of a road through the temple’s grounds. In 1992 building commenced on a Sri Lankan temple in Forest Lake, which moved in 1995 to Ellen Grove. And a Burmese temple was founded in 2007, also in Ellen Grove. A number of additional Theravada temples have been established, and some existing temples have been relocated.

Connections with National Traditions

Theravada Buddhists share a common religious doctrine, ritual practices, and scriptural language (Pali), national traditions are strong. Most, but not all, Theravada Buddhist temples in South East Queensland are associated with a national group: the Sinhalese, Thais, Cambodians, Lao, or Burmese. Often rituals will be conducted in both Pali and the national language: Lao, Cambodian, Thai, or Burmese (though monks will often provide a running translation for the benefit of English speakers).

Generally, Lao people will go to the Lao temple, Cambodians will go to the Cambodian temple, etc. In this respect, some Theravada Buddhist temples in South East Queensland function partly as social and cultural centres for the national group, as well as places of worship. Some temples offer lessons in the community’s language and culture — classical dance, for example — so that the children of Southeast Asian migrants growing up in Queensland can preserve a connection with their cultural roots.

In recent decades, the internet and relatively cheap air travel have enabled temples in Queensland to develop close networks with Buddhist temples and religious establishments in Southeast Asia, and beyond, contributing to the growth of Theravada Buddhism in Queensland and the function of temples as social and cultural centres. Monks will often travel for short periods from their home temple in Queensland to temples in Southeast Asia, or to Buddhist pilgrimage sites in India, Sri Lanka, and elsewhere. Conversely, monks from Southeast Asia regularly travel to South East Queensland to spend a three-month ‘rains retreat’ in a temple, or to participate in one of the major festivals of the Buddhist calendar. In the case of Thailand, such links are enhanced by the Thai monastic establishment’s ‘missionary’ (thammathut) program, which provides trained monks and funding to promote Buddhism around the world, including Australia. Thus, while the growth of Theravada Buddhism in Queensland is part of the modern Australian story of multiculturalism, it is also a story of the expansion of Theravada Buddhism out of Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia into other parts of the world.

The strength of national traditions lends a diversity to Queensland’s Theravada Buddhist temples. But other factors contribute to each temple’s uniqueness. The ‘city’ temples have a focus on the everyday merit-making needs of their local community, while the ‘forest’ temples — or more precisely, monasteries — have a stronger focus on meditation practice.

Some temples adhere to certain monastic lineages — the Dhammagiri Forest Hermitage in Kholo, for example, aligns with the internationally famous late Thai monk, Ajahn Chah (1918–92). Some promote distinctive meditation styles, such as Dhammakaya meditation. Some temples cater principally to the Southeast Asian migrant community, while others have a stronger focus on teaching Buddhism and especially meditation to the local Queensland community. The recent interest in the United States and Europe in mindfulness and meditation, especially Vipassana meditation, which comes out of the Theravada tradition, has drawn people from the mainstream Australian community to Queensland’s Theravada Buddhist temples

Snapshots of Queensland’s Theravada Buddhist temples

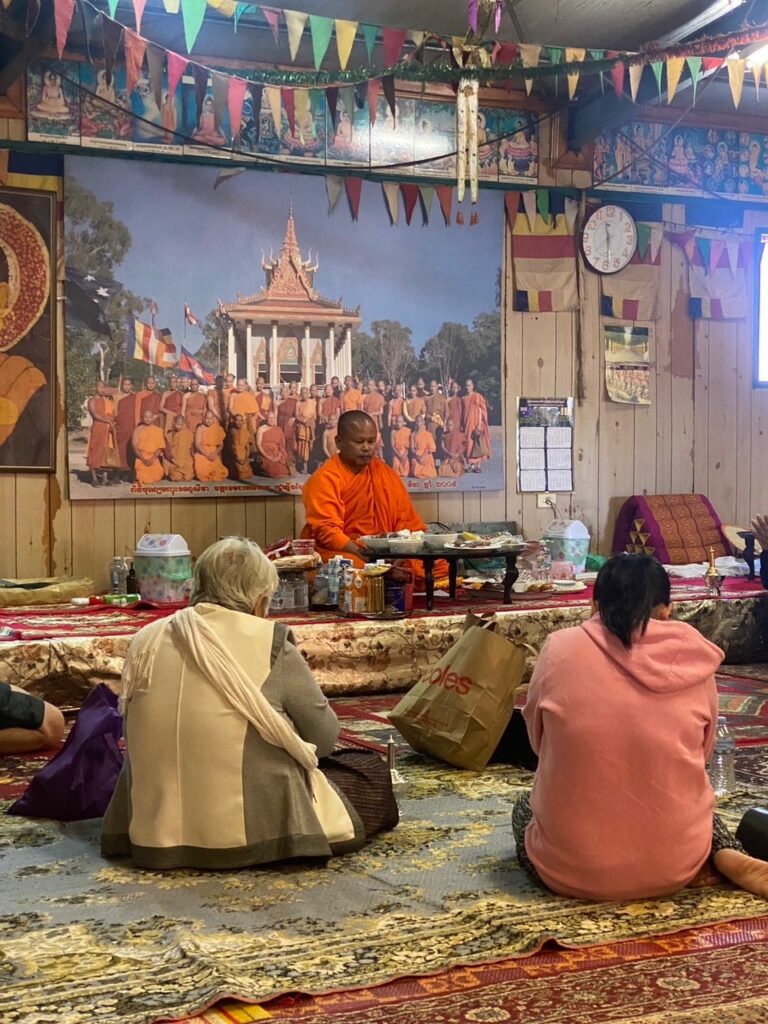

Wat Khemarak Ratanaram (Cambodian)

Wat Khemarak Ratanaram, located in Marsden, Logan, is the main Cambodian Buddhist temple in South East Queensland. The temple is managed by the Khmer Buddhist Society of Qld Inc. and serves a Cambodian-born community of approximately 2700 people as well as locally born Cambodian Australians. One of the oldest Theravada Buddhist temples in Queensland, it was founded in 1990, when the long and bloody civil war in Cambodia was coming to an end. Australia played a key role negotiating the peace agreements ending the war and provided peacekeeping troops as part of the United Nations Transition Authority in Cambodia. Such was the significance of Australia’s contribution to Cambodia, that the Supreme Patriarch of Cambodia, Thep Vong, who played a crucial role in re-establishing Buddhism in Cambodia following the catastrophic Khmer Rouge period, travelled to Queensland to preside over the beginning of the construction of the temple’s ordination hall in 1991. Built in the classic Cambodian style the ordination hall stands out as the most spectacular example of Theravadin temple architecture in Queensland. Today the temple is also a cultural centre for Brisbane’s Cambodian community. Besides religious services the temple also hosts the Wat Khemarak Ratanaram Dance Group which preserves and teaches Cambodian classical dance. The temple enjoys close relations with the Logan City Council.

Figure 5: Ordination Hall, Wat Khemarak Ratanaram, with bodhi tree in the right foreground, August 2023 (QAR).

Wat Thai Buddharam (Thai)

At almost 20,000 people — including residents and international students — Thais constitute the largest population of Theravada Buddhists in Queensland. Of the four Thai Buddhist temples currently in South East Queensland, Wat Thai Buddharam is the oldest. It was originally established in 1991 in Ellen Grove, but moved to its current location in the bushland suburb of Forestdale, Logan City, in 1996.

The founding of Wat Thai Buddharam took place partly due to Thailand’s ecclesiastical establishment’s missionary program to spread Buddhism to other parts of the world. The founder of the temple was the late ecclesiastical governor of the Thai province of Kanchanaburi, Phra Dhammakhunaporn. Phra Dhammakhunaporn was also instrumental in the founding of Wat Thai Nakhon Melbourne, in 1986. This temple is thus the ‘parent’ temple of Wat Thai Buddharam.

The current abbot of Wat Thai Buddharam is Ven. Chonlatish Chanhorm. He studied at one of Thailand’s most famous temples, Wat Paknam Phasi Charoen in Bangkok. He achieved the highest level of Pali language examinations (‘Pali 9’) as well as bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Thai universities. In 2000 he was asked by senior monastic officials in Thailand to help develop Buddhism in Queensland, becoming abbot of the temple in 2007. In 2011 he received a prestigious royal title from the king of Thailand, ‘Phra Siphutthiwithet’, for his services to Buddhism. At present Ven. Chonlatish is also Vice President of the Queensland Sangha (‘Buddhist monkhood’) Association Inc. and Secretary of the Union of Thai Sanghas in Oceania, an association that represents Thai Buddhist temples in Australia, New Zealand, and the Pacific.

Besides religious services Wat Thai Buddharam is a major social and cultural centre for Brisbane’s Thai community. The temple offers Thai language and culture classes for the children of Thais living in Brisbane. The temple hosts the popular Thai New Year (‘Songkran’) and Kathina Ceremony which attract thousands of participants from the Thai, Southeast Asian and broader Brisbane community, including representatives of the state and local government and their opposition counterparts.

The temple led an important innovation for the performance of merit-making rituals for the deceased, which are important in Theravada Buddhism. Initially due to health regulations the ritual could not be held since the body could not be retained at the temple. Through negotiations with local government and health authorities the temple was eventually granted permission to keep the body of the deceased at the temple for seven days to allow relatives and friends of the deceased to pay their respects and the monks to perform the necessary rituals.

Wat Thai Buddharam has numerous outreach activities. It offers meditation classes taught in English every Wednesday and organizes meditation retreats. The temple also maintains close relations with other Theravada Buddhist temples, in particular the Lao and Cambodian temples.

Since the temple does not have its own ordination hall, the Cambodian temple permits Wat Thai Buddharam to use its ordination hall for the ordination of monks. Monks will often take part in rituals at other temples in Brisbane. The temple is active in the Queensland Sangha Association, established in 2007, which represents Buddhist monks and nuns from the three Buddhist traditions: Theravada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana.

Every New Year the temple hosts a ‘Nine International Temples Merit-Making Tour’, when the monks and the laity visit nine other Buddhist temples in Brisbane, including the Burmese, Sri Lankan, Lao, Vietnamese, Korean, Tibetan, Taiwanese, and Cambodian temples, and the Dhammagiri Forest Hermitage.

Jetavana Myanmar Monastery

The Jetavana Myanmar Monastery is a Theravada Buddhist temple in the Burmese tradition situated in the semi-rural Brisbane suburb of Ellen Grove. It is managed by the Queensland Burmese Buddhist Association Inc. (QBBA). The Association was established in 2000 by Burmese migrants to Queensland, which today totals approximately 4000 persons, with the intention of promoting the Theravada Buddhism of the Burmese tradition.

A key moment in the history of the temple was when a local Vietnamese-Australian businessman with a deep interest in Buddhism allowed monks to live on land he had purchased in Ellen Grove so that they could perform religious activities. The businessman later agreed to sell the land to the Association. With the assistance of senior monks from Sydney, the QBBA invited two Burmese monks who were then studying in India to come to Queensland in 2005 to help establish a temple. Following extensive consultation between the QBBA and the local council and relevant government departments, approval was eventually granted for the construction of a temple on the site. A building comprising the monks’ residences was constructed in 2017. An ordination hall was later constructed. Numerous religious items including Buddha images and a large temple bell have been brought in from Myanmar. Expenses for the construction of the temple were met by fundraising among the Burmese community in Queensland, Australia, and internationally. Today two monks reside in the temple.

The Jetavana Myanmar Monastery offers regular services for the Burmese Buddhist community. As in all Theravada traditions, the daily practice is to offer food to the monks. The temple also celebrates major festivals of the Burmese Buddhist calendar including the Myanmar New Year Festival, Vesak, the Rains Retreat, and Kathina Robes Offering Ceremony.

Figure 10: Buddha image, Jetavana Myanmar Monastery, with bodhi tree behind the image shrine, August 2023 (QAR).

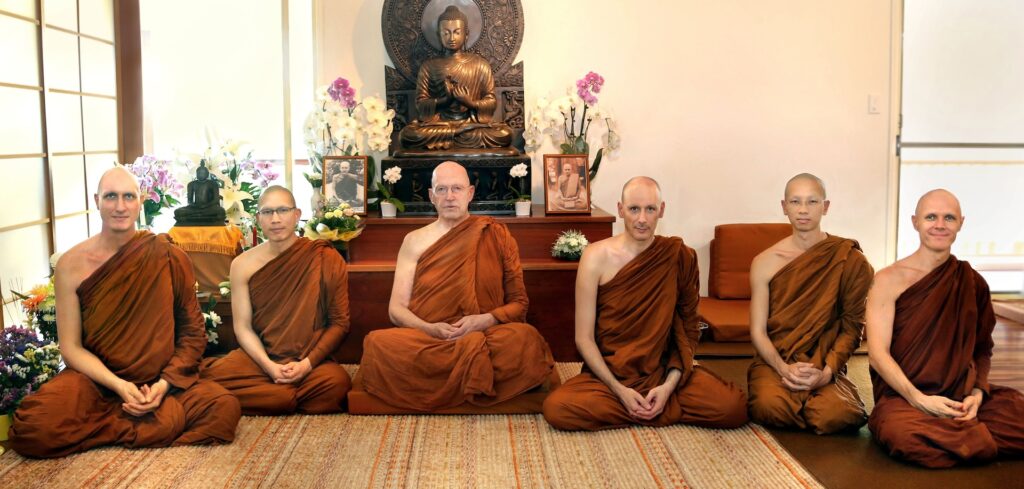

Dhammagiri Forest Hermitage

The Dhammagiri Forest Hermitage is located on a forested hillside adjoining D’Aguilar National Park in the suburb of Kholo in outer Brisbane. It was established in 2007 and is stewarded by the Brisbane Buddhist Vihara Inc.

Dhammagiri has a number of features which distinguish it from other Theravada Buddhist temples in Queensland. The rural location was specially chosen since the hermitage was established in the forest monastery tradition. This tradition within Buddhism places a greater emphasis on seclusion from the outside world, a strict adherence to the Vinaya or monastic rules, and a focus on solitary meditation practice.

The founding abbot of Dhammagiri Forest Hermitage is Ajahn Dhammasiha. Dhammasiha was born in Germany and ordained as a monk in Sri Lanka. He has been in the monkhood for 27 years. Before coming to Queensland, he was a bhikkhu at the Vimokkharam Forest Hermitage in Melbourne. He encountered the Ajahn Chah tradition in Australia and studied under a number of renowned Thai monks in that tradition.

In 2006 the Brisbane Buddhist Vihara proposed that a forest hermitage be established in Brisbane and that Dhammasiha be invited to be its inaugural abbot. The present 75-acre site was purchased with funds donated by the faithful in 2007, making it the largest such hermitage in Queensland. An additional 10 acres was later acquired when a neighbour decided to sell his land, again financed through local and international donations. An important source of support for the Hermitage has come from Ajahn Chah’s monastery, Wat Nong Pa Pong, in northeastern Thailand. In 2009 Luang Por Liem, abbot of Wat Nong Pa Pong, visited the hermitage to advise the abbot on how it should be developed. In 2009 the temple was formally recognised by Thailand’s Wat Pah Nanachat monastery as an associated monastery in the tradition of Ajahn Chah. The Hermitage enjoys close links with the international network of monasteries in the Ajahn Chah tradition, and hosts visits by internationally recognised monks.

Between two and three monks usually reside at the Hermitage. While its focus is on solitary meditation practice, it offers meditation classes and retreats for a limited number of practitioners. The Hermitage also produces regular ‘Dhammagiri Buddhist Podcasts’, which discuss various aspects of Buddhist teaching.

While the impetus for the founding of Dhammagiri Forest Hermitage came from the Sinhalese Buddhist community, the Hermitage is now also frequented by the local Brisbane community as well as by Chinese, Vietnamese, and Cambodians. The Hermitage’s association with Thailand’s Ajahn Chah tradition also attracts many Thais.

Wat Phra Dhammakaya Brisbane

Wat Phra Dhammakaya temple in the Brisbane suburb of Wooloowin is part of a famous network of Thai Buddhist temples. Dhammakaya is the name originally given to a distinctive meditation technique developed by a renowned Thai monk, Luang Phor Sot, of the Bangkok temple, Wat Paknam Phasi Charoen. The temple’s influence grew from the 1970s at a time of rapid economic and social change in Thailand, under its charismatic leader, Phra Thammachaiyo, and influential supporter, the nun Mae Chi Chandra. The temple and its meditation technique became popular first among university students and later among the growing middle class. It was one of the first Buddhist movements to use modern media techniques to promote their message — in 2002 Dhammakaya set up a cable television channel, the Dhammakaya Media Channel, now renamed, the Global Buddhist Network.

The temple’s popularity in Thailand grew rapidly, and from the 1990s the Dhammakaya network began to expand overseas. A distinctive feature of the Dhammakaya network is its strong missionary focus on promoting Buddhism and the Dhammakaya meditation technique internationally. At present there are approximately 86 Dhammakaya centres worldwide outside Thailand.

In Australia there are five Buddhist temples in the Dhammakaya tradition. The first Dhammakaya temple was founded in Sydney in 1997. In Brisbane, prior to the purchase of a temple, the Dhammakaya monks stayed at a devotee’s house. Wat Phra Dhammakaya Brisbane was founded in 2006 when a two-storey house was purchased in Wooloowin, financed partly by a wealthy donor in Thailand. The current abbot, Phrakhru Worayanavithes, was selected by Dhammakaya headquarters in Bangkok to come to Brisbane to take charge of the temple. Currently four monks reside there. While many of the temple’s devotees are Thais, it has a strong focus on providing services to the local Brisbane community, in line with Dhammakaya’s mission. The temple hosts a Brisbane Meditation Centre which coordinates free meditation classes taught in English as well as three-day retreats. On Saturday and Sunday mornings monks from the temple will travel to Sunnybank or Woodridge Markets where there are numerous Southeast Asia food stalls to perform the bintabaht ritual, where lay Buddhists will offer food to the monks as alms.

Dhamma Rasmi, Vipassana Meditation Centre Queensland

Some mention should also be made of the Vipassana Meditation Centre Queensland, also known as Dhamma Rasmi, located on 50 acres of bushland in Pomona in the Sunshine Coast hinterland, 30 kms from Noosa. The property was acquired in 1993. The Centre’s principal function is to offer courses in Vipassana meditation, a distinctive variety of meditation in Theravada Buddhism. The tradition was popularised by the former Accountant General of Burma and later celebrated meditation teacher, U Ba Khin (1889-1971). Ba Khin’s most famous student was the Indian-Burmese businessman, S. N. Goenka (1924-2013). Following Ba Khin’s death Goenka was responsible for taking his Vipassana meditation technique and promoting it around the world. Today there are almost 250 Vipassana meditation centres globally, teaching the Ba Khin meditation method. Dhamma Rasmi offers 10-day meditation courses as taught by S. N. Goenka. It can accommodate up to 70 practitioners.

Conclusion

While Theravada Buddhism’s history in Queensland is relatively recent, dating from the early 1980s, since then it has experienced significant growth. The Sri Lankan Buddhist community had an early pioneering role, but with the migration of Laos, Cambodians, Thais, and Burmese, these groups have been very active in establishing temples in their respective national traditions. The temples have multiple roles. They offer religious services and spiritual support for local Theravada Buddhist communities; they teach the fundamentals of Buddhism; they act as centres to preserve the cultural traditions of the local community; they are centres for the non-sectarian promotion of meditation; and some keep alive the more austere forest monastery tradition.

Queensland’s Theravada Buddhist temples cater both for Southeast Asian communities and the broader local Queensland community. While Southeast Asian communities tend to be most active in merit-making activities, the local Queensland community has shown significant interest in meditation practice and, in some cases, learning the fundamentals of Buddhism.

Lastly, a notable feature of Queensland’s Theravada Buddhist temples is their close connections with temples, monks, and monastic establishments in Southeast Asia, Sri Lanka, and other parts of the world, made possible through easier travel and the internet. Charismatic monks, lineages, and temples in Southeast Asia provide inspiration and other sources of support for Queensland’s Theravada Buddhist temples. The success of Theravada Buddhism in Queensland is thus a story both of multiculturalism and acceptance of religious diversity in Australia, as well as the expansion of Theravada Buddhism beyond Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia to other parts of the world.

With thanks

The author thanks the abbots, monks, and lay supporters associated with the temples and monasteries discussed in this essay for their generous contribution to the research.

Sources and Further Reading

“Australia’s Population by Country of Birth 2022”, Australian Bureau of Statistics, https://www.abs.gov.au

Braun, Erik. 2013. The Birth of Insight: Meditation, Modern Buddhism, and the Burmese Monk Ledi Sayadaw. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Chanhorm, Ven. Chonlatish. 2022. Oral history interview, Wat Thai Buddharam, 1 December. Interview by Patrick Jory.

Chor Ma Thwe. 2023. Oral history interview, Queensland Burmese Buddhist Association Inc., 29 September. Interview by Patrick Jory.

Croucher, Paul. 1989. A History of Buddhism in Australia, 1848–1988. Sydney: UNSW.

Dhammasiha, Ajahn. 2023. Oral history interview, Dhammagiri Forest Hermitage, 3 March. Interview by Patrick Jory.

“Five Years Dhammagiri: An Account of Origins and Main Events (Highlights Only), On the Occasion of our 5th Anniversary on 28-29 April 2012.” Unpublished manuscript.

Halafoff, Anna, Cristina Rocha, and Juewei Shi. 2022. “Flows and Counterflows of Buddhism ‘South of the West’: Australia, New Zealand, and Hawaiʻi”. Journal of Global Buddhism 23, 2: 95–104.

Htut, Assoc. Prof. Dr. Thein. 2023. Oral history interview, Jetavana Myanmar Monastery, 27 August. Interview by Patrick Jory.

Monk “Pich”. 2023. Oral history interview, Wat Khemarak Ratanaram, 19 August 2023. Interview by Patrick Jory.

Sarath-Chandra, Rahubadde. 2013. “History of Buddhism in Queensland, Australia: Some Reminiscences.” Unpublished manuscript.

Worayanavithes, Phrakhru. 2023. Oral history interview, Wat Phra Dhammakaya, Brisbane, 1 February. Interview by Patrick Jory.

Related articles