Protestants, Catholics, and the Queensland Irish Association

Protestant-Catholic tensions have been an enduring feature of Queensland social life. The Queensland Irish Association, despite its avowed anti-sectarian stance, has been entangled in these tensions, especially in the fractious interwar period.

By Rodney Sullivan and Robin Sullivan

This is a 22 minute read, published June 2024.

In February 1999 Gerry Adams, President of Sinn Féin, the political wing of the Irish Republican Army (IRA), visited Brisbane. While a hero to most Irish nationalists, Adams was a divisive figure, a veteran of the struggle to bring Northern Ireland into a united and independent Ireland and interned as a suspected terrorist in the 1970s. He was tainted by his association with IRA violence, not least its 1990 murder by mistake of Brisbane-born lawyer Stephen Melrose while on holiday in Holland.

A City Hall reception, followed by lunch at the Queensland Irish Association, generated controversy. Protestors, including Melrose’s father, gathered at City Hall under a banner that read ‘Murderer’ in red letters. At Tara House, the QIA’s long-standing venue in Elizabeth Street, the lunch for 500 members and guests was a success until Adams produced a large rubber bullet from his coat pocket. “This is what the Security Forces and Police are using on our children,” he declared to the stunned audience. The gesture led to the resignation of five members of the QIA registering their disapproval of Adams’s presence in Tara House. QIA President Pat Brennan tried to mollify internal critics with the assurance that should the Ulster Protestant firebrand the Rev. Ian Paisley visit Brisbane, he, too, would be received at Tara House (Sullivan, 2023: 176).

Religious sectarianism — in this instance, mutual enmity between Protestant and Catholic, stoked by the politics of independence in Ireland — has historically been a pervasive theme in Queensland life, but one that is today easily overlooked. In the 1920s and 1930s, for example, the Queensland Irish Association was embroiled in a series of sectarian surges. The earlier tensions that accompanied its foundation, political debates in World War One and the 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin have been analysed in some detail (Sullivan, 2013: 8–16, 43–48). In the interwar period, the Depression intensified this denominational competition and conflict, which, in the late 1930s, became a political and parliamentary fixation. During World War Two sectarianism lay dormant, but, as Murphy (1980b) has shown, erupted again in the 1950s. In surveying this history we will close with a brief assessment of the relevance of religion to the Irish Association in the far more secular twenty-first century.

Figure 1: Queensland Irish Association building, Elizabeth Street, Brisbane, c. 1928 (State Library of Queensland).

What is sectarianism?

The dominant form of Australian sectarianism was shaped by English conquest and colonisation of Ireland. The impact of this conflict was compounded by the distinctive role of religion in Britain. Protestantism was a pillar of the state and a unifying force in the British Empire. As Hilary Carey (2011: 43) pointed out, it was primarily the Bible and anti-Catholicism that bound British Protestants together. Britain’s tradition of anti-Catholicism, summed up in the ‘No Popery’ cry, was disseminated among overseas colonies. It was a potent commodity. In his pioneering study of British anti-Catholicism E.R. Norman (1968: 20), noted its strength and singularity. It was ‘chauvinistic’, but deeply entrenched in both society and state.

Historians of Christianity have applied the term ‘sectarianism’ to conflict between Catholics — particularly Irish Catholics — and British Protestants. In his study of Protestantism in New South Wales between 1900 and 1914, Richard Broome (1980: 95) used the terms ‘sectarian’ and ‘sectarianism’ to refer to ‘religious animosity, specifically Protestant-Catholic conflict’. Jeff Kildea’s Tearing the Fabric (2002: ii) added another layer — ethnicity — pointing out that, in Australia, theological disagreement was compounded by intense rivalry and competition between ‘Irish Catholics, on the one hand, and English Anglicans and Scots-Irish Presbyterians on the other’. Kildea also referred to the sectarian dilemma: what one denomination might regard as a legitimate or defensive act or comment, another might interpret as illegitimate and offensive:

… sectarianism, though universally disapproved, was frequently practised — always by the other, never by oneself. To Catholics it described the anti-Catholic bigotry and injustice of the Protestant majority; to Protestants it meant the tendency of Catholics, whom they regarded as subject to the sinister and authoritarian forces of Rome, to segregate themselves from the mainstream of community life, while persistently and disruptively demanding special treatment from the rest of the community (Kildea, 2002: ii).

Using the Queensland Irish Association as a focus, the multi-dimensional nature of sectarianism becomes clear, with evident patterns as it waxes and wanes. It appears as a compound of interacting and sometimes transitory elements, including religious denomination, ethnicity, identity, economics and politics. These elements coalesced in Ireland with implanted Protestant unionism centred in Dublin and the North, which harboured a fierce determination to be part of Protestant Britain rather than Catholic Ireland. In the main, behavioural sectarianism was practised by a tiny and vociferous minority, but, at propitious times, these few activists could recruit much larger cohorts (Vaughan, 2022: 3). They were assisted by the sectarian dilemma, where a defensive denominational posture or action is interpreted by others as aggression, triggering a spiral of intensifying hostile exchanges. Throughout its 125-year history, the QIA sought to insulate itself from Protestant-Catholic conflict by embracing pan-denominational Irishness.

… fast becoming a thoroughly Roman Catholic colony and a mere province of the Popedom.

The Irish and Catholics in Queensland

Queensland is one of the most Irish and Catholic parts of Australia. Sectarianism came with the first arrivals from Britain, such that the 1825 penal colony at Moreton Bay resembled an Irish prison camp. Protestant military guards, formerly stationed in Ireland, imposed discipline and inflicted punishment on predominantly Irish Catholic prisoners (Evans, 2007: 19, 88). In the late 1840s, Dr John Dunmore Lang (1864: 3), the Presbyterian clergyman and Moreton Bay representative in the New South Wales Legislative Council, warned that New South Wales, (including Queensland until 1859), was ‘fast becoming a thoroughly Roman Catholic colony and a mere province of the Popedom.’ In 1849, the first of some 600 Lang-sponsored Protestant immigrants arrived in Brisbane from Scotland. When considered in sectarian terms, their mission was to eliminate ‘Popery’ and reduce the influence of the Irish Catholic minority (Baker, 1967).

By 1911, Catholics, some 80 per cent of whom were of Irish birth or descent, constituted 24.71 per cent of Queensland’s population, the highest proportion in Australia after New South Wales, which recorded a figure of 25.51 per cent. In Brisbane, Catholics constituted 22.98 per cent of the population, again second, among the capital cities, to Sydney’s 24.63 per cent (Knibbs, 1914, 1: 201, 213). Irishness has endured in Queensland: in the 2021 Census (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2021) significantly more Queenslanders, some 11 per cent, claimed Irish ancestry as compared to the Australian average of 9.5 per cent.

The Queensland Irish Association, avowedly non-sectarian and non-political, was founded during the ethno-sectarian hostilities of the mid-1890s (Sullivan, 2023: 8–11). The former members of a volunteer militia based on ethnicity, the Queensland Irish Volunteers, reconstituted themselves as the QIA on 23 March 1898. Its first object was an optimistic commitment ‘to promote the union and brotherhood of Irishmen and their descendants irrespective of creed into one great party on the common platform of national freedom and community of interest.’ The majority Catholic membership demonstrated its commitment to denominational neutrality by electing John Kingsbury, a Dublin-born Methodist as inaugural President.

In promoting a free and united Ireland, the QIA was investing confidence that the future of its homeland had been mapped out in Home Rule legislation introduced into the British parliament in 1886. This envisaged the replacement of direct rule from London with self-governing dominion status, similar to that enjoyed in Queensland. It assumed Protestant-Catholic conflict would decline as the two communities identified as Irish, rather than as Irish Catholics or Irish Protestants. However, in time, religious differences were amplified by ethnic, economic, and historical factors. Rather than identify as Irish, the Protestant majority in the North of Ireland embraced Ulster British identities, widening the cleavage between them and their Catholic counterparts (Elliot, 2013). Managing the duelling identities of Irish Catholic and Ulster Protestant was an evolving challenge for the QIA for the next century and a quarter.

The QIA and 1920s sectarianism

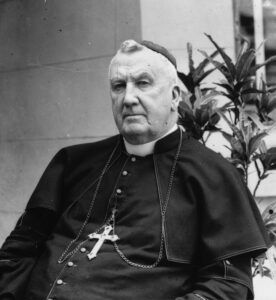

Irish Catholics entered the 1920s in defensive mode, reeling from sectarian attacks and discrimination which intensified following Dublin’s 1916 Easter Rising against continuing British rule. In 1921 Catholic laymen, following the New South Wales example, established a Queensland branch of the Knights of the Southern Cross. This was a secretive pro-Catholic organisation, modelled on the US Knights of Columbus founded in the early 1880s. Initially, it sought to counter discrimination against Catholics in employment and business. There was considerable cross-membership between the Knights and the QIA, with the latter contributing at least ten of the Knights’ fifty foundation members. It seems clear that the Knights of the Southern Cross, comfortable with the title ‘Bishop’s Men’, were under the influence, if not control, of Archbishop James Duhig who attended their meetings (Buch and Roberts, 2016: 32, 267–68).

In such a setting, the Queensland Irish Association struggled to observe its foundational principle: to conduct activities ‘on strictly non-sectarian and non-political lines’ (Queensland Irish Association, 1924: 4). However its Catholic majority, and Irishness, ensured that the organisation and prominent members would, on occasion, be entangled in conflicts with a sectarian dimension.

Brisbane’s Centenary Pageant of Nations in 1924, for example, sparked a dispute between the QIA and the Ulster and Loyal Irishmen’s Association (ULIA), a bastion of Protestant unionism, over which organisation could represent Ireland. Brisbane’s staunchly Irish Catholic Mayor, Maurice Barry, ruled that the QIA alone should represent the whole of Ireland, consigning a dismayed ULIA to the miscellaneous category (Sullivan, 2023: 50-51).

The 1926 feast of St Patrick illustrated the challenge faced by the QIA as it tried to be both Irish, in the Catholic nationalist mode, and non-sectarian. The Association’s display in the St Patrick’s Day Parade was conciliatory and inclusive, appealing for unity between the North and South of Ireland, and harmony between Catholics and Protestants. The float highlighted the words of a nineteenth century poet, Jean de Jean Frazer, a Presbyterian Irish nationalist, who, for the 1843 Battle of the Boyne commemoration, crafted a Catholic’s appeal to a Protestant for solidarity (cited in Sullivan, 2023: 79):

And let the Orange lily be

Thy badge, my patriot brother —

The everlasting Green for me;

And — we for one another.

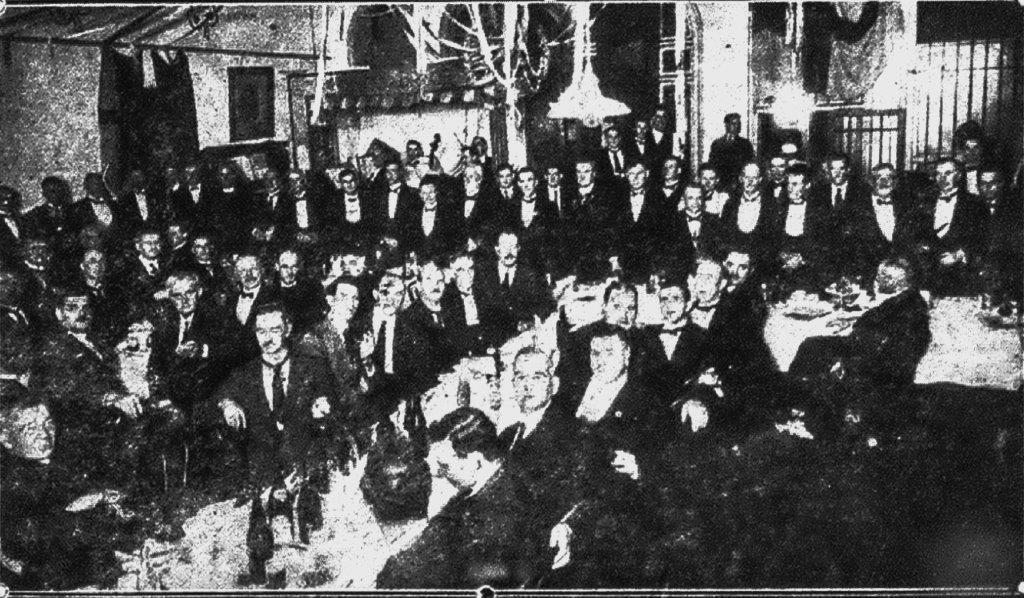

The St Patrick’s Eve Dinner, however, led to a public sectarian quarrel. In proposing the toast ‘The Day We Celebrate’, the QIA President, Catholic barrister Neil MacGroarty, lauded the executed rebels of the 1916 Rising and Sinn Féin’s success in carving out the Irish Free State from the union with Britain in 1921. He was applauded as he declared: “In 1921 Sinn Féin did what Germany failed to do. The greatest Empire of modern times bowed to Ireland and asked for terms. There was no parallel to that in ancient or modern history” (Catholic Advocate, 18 March 1926: 6).

The President of the Queensland Council of Churches, Rev. Norman Millar, soon counter-attacked in an Ann Street Presbyterian Church sermon. He condemned Macgroarty’s oration as Irish Catholic impertinence. Criticism of the British Empire, which he believed to be divinely ordained, was beyond the pale. Macgroarty, he charged, had either a defective conscience or a mind ‘poisoned by unappeasable race hatred’ (Daily Mail, 22 March 1926: 27).

Figure 4: 1926 St Patrick's Eve Dinner, Queensland Irish Association (Catholic Advocate, 25 March 1926, p. 9).

Sectarianism and politics in the 1930s

The 1930s spike in sectarianism had many similarities to that of the 1890s. It occurred during an economic depression amid fierce competition for employment, especially in the public service. It was also associated with Protestant cries that Catholics had acquired disproportionate political power and were receiving preference in public service recruitment and promotions.

Catholic grievances added fuel to the 1930s outbreak. The 1929–1932 austerities implemented in Queensland by Arthur Moore’s conservative government included severely trimming state funding to Catholic schools, abolishing St Patrick’s Day as a public holiday, and denying church schools access to subsidised relief labour. Archbishop James Duhig held Moore’s Attorney-General, Neil Macgroarty, President of the Queensland Irish Association and the only Catholic cabinet minister, accountable. In the 1932 state election he deployed Knights of the Southern Cross to help replace Macgroarty with Labor’s Vincent Gair, a fellow Catholic and a senior member of the Knights (Boland, 1986: 264–65; Costar, 1981: 133; 2003: 269; Buch and Roberts, 2016: 275).

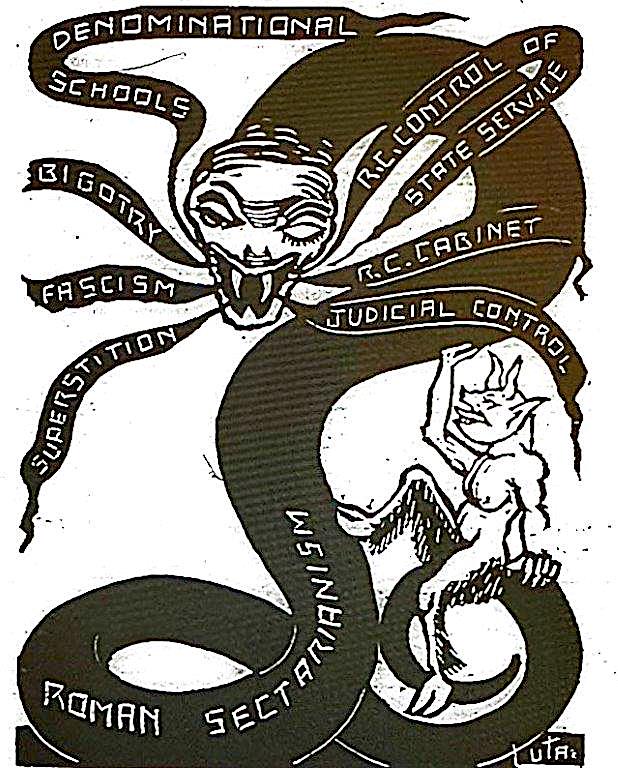

As sectarianism intensified at this time, the Knights of the Southern Cross were on the Catholic side of a matrix of interacting lay organisations that pursued denominational objectives and engaged in forms of sectarian conflict. It had some similarities to a Protestant adversary, the Queensland Loyal Orange Institution (LOIQ), established during the 1860s. Originating in 1790s Ireland, the Orange Institution exemplified militant anti-Catholicism, both in the Irish context and in Anglo-Irish settler colonies like Queensland.

Catholics were excluded from membership and intending members were required to affirm: ‘I am not, nor have I ever been a Roman Catholic. I am not, nor have I ever been married to a Roman Catholic’ (Queensland Loyal Orange Institution, 1907: 55). The qualifications for an Orangeman, read at every meeting, urged a militant anti-Catholicism:

He [the Orangeman] should love, uphold and defend the Protestant religion, and sincerely desire and endeavour to propagate its doctrines and precepts. He should strenuously oppose the encroachments of sacerdotalism, and the fatal errors and doctrines of the Romish and Greek Churches … and should scrupulously avoid countenancing (by his presence or otherwise) any act or ceremony of Popish or false worship. He should by all lawful means resist the ascendency (particularly) of the Church of Rome, its encroachments, and the extension of its power … (Queensland Loyal Orange Institution, 1907: 8).

The apparent political influence of Catholics energised the Orange Institution. It was bolstered by other sectarian organisations such as the United Protestant Association (UPA), founded in 1935 by Presbyterian Rev. James Gillespie, and the Protestant Labour Party (PLP), established by the UPA in 1937. The primary objective of the PLP echoed the Orange Institution’s conviction that Protestantism was a prerequisite for individual freedom and dignity: ‘Maintenance of Protestantism in Queensland’ was vital, the PLP declared, ‘because it is recognised that when Queensland ceases to be Protestant, it ceases to be free’ (Protestant Clarion, 27 January 1938: 2).

Figure 5: Queensland Irish Association float, 1937 St Patrick's Day Parade, Brisbane (State Library of Queensland).

Earlier in the decade, the vexed issue of State aid to church schools proved crucial in Queensland’s 1932 election (Campion, 1987: 259–65). Despite Catholic pressure during the campaign, Moore refused to reinstate funding to denominational schools. From opposition the Labor Party promised restoration, receiving Archbishop Duhig’s endorsement. Knights of the Southern Cross and Duhig, with Vincent Gair as go-between, joined in battle against the Moore government. Labor won the election decisively with a 30-seat majority, and Gair defeated Macgroarty in South Brisbane, providing Archbishop Duhig with ready access to the new Labor government, led by a Presbyterian Scot, William Forgan Smith.

The contrasting denominational compositions of the pre-and-post-1932 election ministries registered with Protestants: one Catholic out of ten in the Moore ministry, seven Catholics out of ten in the Forgan Smith cabinet. The numbers spoke of a marked shift in denominational political power. Moreover, Forgan Smith’s Presbyterianism provided little comfort for ultra-Protestants. In 1933 he declined an Orange Institution invitation to join dignitaries for the annual 12 July celebrations (Costar, 1981: 133).

Catholic advocacy and the Protestant Labour Party

In 1937 the Catholic Taxpayers’ Association, founded the previous year, launched an energetic campaign for increased state funding for Church schools. Archbishop Duhig was its public voice, with Knights of the Southern Cross discreetly directing operations (Catholic Advocate, 20 May 1937: 12; 17 June: 20).

The campaign stoked anti-Catholic feeling, as when Rev. Norman Millar, speaking on behalf of the Protestant-only Queensland Council of Churches, labelled Catholic Taxpayers’ Association lobbying of politicians ‘a most mischievous intrusion of sectarianism into politics’ (Telegraph, 7 July 1937: 1). The Courier-Mail (29 July 1937: 12) urged Catholics to abandon their campaign in the face of a Protestant backlash, further exemplified by a City Hall rally in late October organised by the Loyal Orange Institution that drew some two thousand people.

Speakers included Millar and Rev. Myles Phillips, Secretary of the United Protestant Association. Rev. James Gillespie, founder of the Protestant Defence Association, declared that while Catholics numbered only 20 per cent of Queensland’s population, they ‘held a preponderance of public service positions.’ Somewhat ominously, Millar warned Catholics ‘that the limits of our tolerance and generosity have been reached’ (Courier-Mail, 30 October 1937: 16).

The genesis of the Protestant Labour Party lay in fear that Catholics controlled the ALP and, therefore, the Queensland Government. The PLP’s foundational statement asserted: ‘In a State where Roman Catholics are 19.2 per cent of the population the Labour Party in the State Parliament consists of 27 Roman Catholics and 16 Protestants’ (Courier-Mail, 9 December 1937: 19). Anti-Catholic efforts by a relatively small but vociferous group of Protestant clergy and organisations promised a potent constituency.

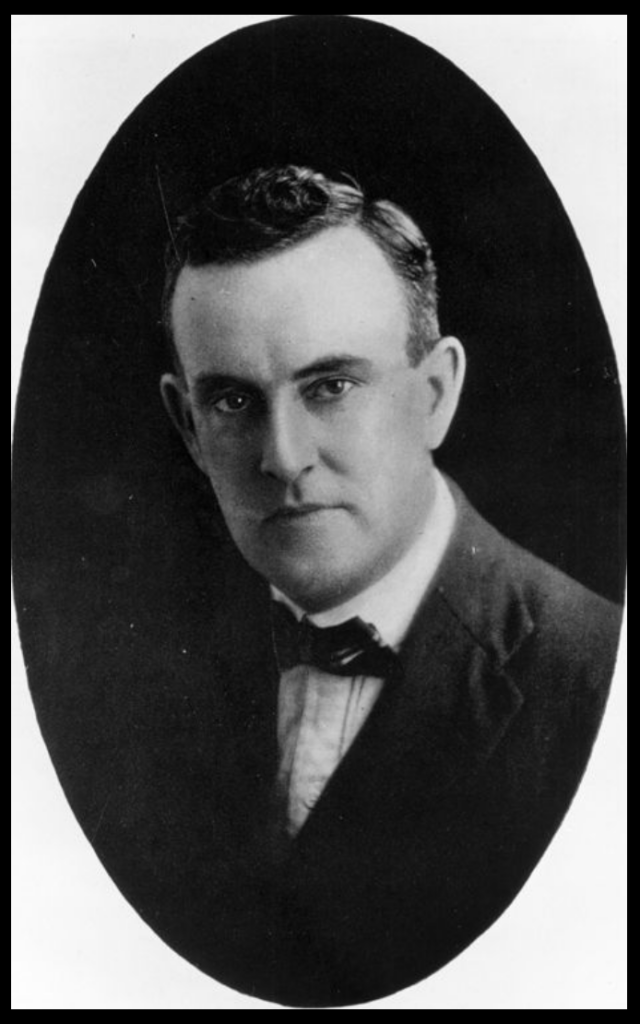

Rev. Norman Millar and Archbishop Duhig were the leading Protestant vs. Catholic public warriors in Queensland life during the 1930s. But away from the spotlight, their adherents were on the march. By 1937, internal sectarian warfare had broken out in the ALP. Methodist James McCann failed to replace Catholic barrister Patrick Copley, Vice-President of the Queensland Irish Association and sitting member for the seat of Kurilpa, as Labor’s endorsed candidate for the following year’s State election. McCann was a Protestant with deep roots in the labour movement. A former president of both the Painters’ and Decorators’ Union and the Trades and Labour Council, he had led Brisbane’s 1929 Labour Day procession together with Catholic Premier William McCormack. In 1936 he became foundation president of the Hill End branch of the United Protestant Association. Having failed to displace Copley within the ALP, McCann defected to the Protestant Labour Party (Telegraph, 6 May 1929: 9; 30 March 1938: 3; 31 March 1938: 9; Sunday Mail, 12 December 1937: 15).

Vincent Gair was McCann’s next target. There was no more active Catholic lay warrior in the 1930s than Gair, MLA for South Brisbane. He joined the Irish Association in 1936, the same year he became Junior Deputy Grand Knight of the Queensland Knights of the Southern Cross, a post he held for the next three years of sectarian hostilities (Buch and Roberts, 2016: 276). The PLP endorsed McCann in an attempt to remove Gair from his South Brisbane seat in the 1938 state election, one of the most visibly sectarian manoeuvres in Queensland politics since 1896 (Fox, 1980). What weight can ultimately be given to religious considerations in McCann’s decision to abandon the ALP, and the role played by thwarted ambition, remain largely matters of conjecture.

Gair and the ALP received an electoral shock in the election of 1938. In South Brisbane McCann ran a vigorous campaign, polling 20 per cent of the votes, most stolen from Gair, who narrowly retained the seat on preferences. The PLP candidate and Methodist George Morris defeated Labor’s Frank Waters in Kelvin Grove (Costar, 2003: 270). The sole PLP member to win a seat, Morris nevertheless brought a loud ultra-Protestant voice into the Queensland Legislative Assembly. According to Gair, he was a sectional candidate whose success ‘blotted the history of the Parliament of Queensland’ (QPD, 11 October 1938: 314). Illustrating the subjective dimension of sectarianism, Morris responded that Gair and the ALP were the real sectionalists, promoting minority Catholic interests at the expense of the Protestant majority (QPD, 11 October 1938: 796). Edmund Maher, Catholic leader of the Country Party, pointed to economic forces underlying denominational conflict, arguing that sectarianism was not so much about religion as competition for jobs (QPD, 11 October 1938: 828).

In his maiden speech Morris reiterated Protestant complaints that the Government was controlled by Catholics, favouring them and their institutions in funding decisions. He alleged that 75 per cent of the public service and police force were Roman Catholics, and that Archbishop Duhig was £10,555 in arrears with diocesan rates, with no action under way to recover the sum. He charged Catholic Minister for Health and Home Affairs Ned Hanlon and Police Commissioner Cecil Carroll with sustained anti-Protestant bias (QPD, 24 August 1938: 114–16).

Morris’s ultra-Protestantism nurtured his paranoia, or perhaps it was the other way round. Paranoia also inflated, and in some cases concocted, ultra-Protestant claims about the preponderance of Catholics in the public service. This was demonstrated by Labor Treasurer Frank Cooper, an Anglican, who refuted allegations of over-representation of Catholics. He took as an example the PLP’s electioneering claim that 700 of the 900 employees in the State Insurance Office were Catholics. The Office had been in his portfolio and he remarked that rather than a total of 900 it employed only 474 people. Similarly it was alleged that in the previous year 82 teachers had been appointed to the Department of Public Instruction, 56 of them Catholics. This too was wildly wrong, as some 237 teachers had been recruited. Cooper was urged to investigate public servants’ religious affiliations but refused on privacy grounds. (QPD, 31 August 1938: 218–20). The historian Denis Murphy also examined claims of 1930s over-representation of Catholics in the public service and likewise found them spurious (Murphy, 1980a: 38).

As Morris sought redress for various grievances against Catholic decision makers it seemed that he invariably encountered unsympathetic Catholics higher up the authority chain: the Under-Secretary for Justice Denis O’Hagan, the Police Commissioner Cecil Carroll, and Police Minister Ned Hanlon. O’Hagan and Hanlon were members of the Irish Association, and Carroll moved the vote of thanks at the 1937 St Patrick’s Eve Dinner.

Morris reserved his most personal fusillade for Catholic barrister, Patrick Copley, Vice-President of the QIA. In 1939 he sensationally alleged that Copley paid £15 to procure a criminal abortion and that police were complicit in his protection, based on allegations made by a young woman against Copley. He implied that the QIA Vice-President had deceived his fiancée by conducting an illicit affair with the complainant, and later paid for her illegal abortion.

When the wronged young woman began accosting Copley at Sunday mass, two police officers detained her, and drove her around in a police vehicle, enabling Copley to walk into the Church, hear mass, and depart with dignity. The allegations against Copley were eventually retracted (QPD, 23 August 1939: 149; 10 October 1939: 762–63).

Sectarian animosity continued in Brisbane while the international environment deteriorated in the late 1930s, as varieties of fascism took hold in Germany, Italy and Spain. The Protestant Labour Party sought to link the Catholic Church with far-right European dictatorships, especially Benito Mussolini’s regime in Italy. The Pope, declared George Morris, was Mussolini’s deputy. Launching an emotional tirade, he alleged not only that ‘Rome had entered into the politics of Queensland’ but also that ‘the Roman Church [was] a system of idolatrous worship … inflicted on the people … the hocus-pocus and mumbo-jumbo of that particular section of the community is being dictated by the medicine man in Rome’ (QPD, 23 August 1939: 148). In his view, Queensland was a Protestant state in which Roman Catholicism was alien, superstitious and unwanted. Some six months later, having undertaken research into Morris’s background, Patrick Copley returned fire when he revealed that Morris had been baptised a Catholic in St Benedict’s Church, Sydney, in July 1892 (QPD, 10 October 1939: 763).

Sectarian tensions also peaked in regional Queensland during the 1930s. The proportion of Catholics in Townsville, for example, was greater than in Brisbane – according to the 1933 Commonwealth Census (Part III: 280) 25 per cent compared to 21 per cent. In 1934 the Mayor, Anglican James Gill, rejected a request from Catholic Bishop Terence McGuire to provide a civic reception for Apostolic Delegate to Australasia, Archbishop Philip Monsignor Bernardini, on his first official visit to Queensland. The rejection, and the Mayor’s comment that such a reception might lower the dignity of the Council, mobilised the city’s Catholics in what became known as the ‘Gill affair.’ A protest meeting in City Hall, with the crowd spilling out into Flinders Street, publicised hitherto suppressed Catholic anger and frustration (Townsville Daily Bulletin, 4 July 1934: 9; Maguire, 1990: 113–15, 151).

Against this backdrop, the 1938 state election in Townsville was overtly sectarian. Protestant Labour Party candidate Albert Loveridge, an Anglican, alleged Catholic control of parliament, attacked state funding of church schools and advocated a freeze on Catholic appointments to the public service. He earned notoriety by falsely branding his opponent, Maurice Hynes, a ‘scab’, for working during the 1911 sugar strike in Mackay. Hynes, Catholic Labor Minister for Labour and Industry, a member of the Irish Association and former union organiser survived though the PLP harvested over a quarter of the Townsville vote. Loveridge was subsequently convicted and fined for defaming Hynes (Townsville Daily Bulletin, 27 January 1938: 9; 30 March 1938: 3; Worker, 23 August 1938: 7, 11; Maguire, 1990: 114).

The outbreak of World War Two in 1939, however, fatally undermined the Protestant Labour Party, and temporarily eased sectarian tensions in Queensland. Such animosities paled in the face of German aggression in Europe and an increasingly assertive Japan in the Pacific. The dominant themes at the 1939 QIA’s St Patrick’s Eve Dinner, therefore, were the necessity of national unity and repudiation of sectarianism. The ageing Archbishop Duhig, a former Irish Volunteer, fused Australian, Irish and Empire loyalty with a call for a war-ready Irish corps (Sullivan, 2023: 84).

Conclusion

The Queensland Irish Association, because of its continuing connection with Ireland and opposition to Ireland’s partition, will inevitably be entangled in sectarian questions for the near future. Even though Catholics in Northern Ireland now outnumber Protestants (Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency, 2021), religious discrimination, segregation and power structures persist (McVeigh and Rolston, 2021). The chances of further domestic sectarian entanglements — such as those of the 1890s, World War One, 1920s, 1930s, and 1950s — appear remote following the post-1950s erosion of religious faiths and denominational identities.

On a visit to Brisbane in 2022, the increasingly popular Opposition Leader in the Republic of Ireland, Sinn Féin’s Mary Lou McDonald, met QIA President Jeffrey Spender, and predicted a referendum on Irish reunification within a decade. Should that happen, and be successful, radical cultural, including religious, adjustments will have to occur to accommodate the Protestant unionist minority.

The Queensland Irish Association, if it is to survive, will also have to adjust to an environment which is less religious and more secular. Irish rebels, Protestant Wolfe Tone in 1798, Catholic QIA hero Kevin O’Doherty in 1848, and the Association’s own constitution in 1898 mapped the route: towards an Irishness transcending denominational affiliations.

Sources and further reading

Government and parliamentary publications

Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2021. 2021 Census. Australian Census, QuickStats. https://www.abs.gov.au/census/find-census-data/quickstats/2021/2201_AUS, accessed 28 December 2022.

Australian Government. 1914. Census of the Commonwealth of Australia, 1911, Vol 1, Statistician’s Report. Melbourne: McCarron, Bird & Co.

Australian Government. 1934. Census of the Commonwealth of Australia, 1933, Part III, Queensland-Population. Canberra: Commonwealth Government Printer.

Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. 2021. Northern Ireland Census 2021. Accessed 20 April 2023.

Queensland Parliamentary Debates (QPD), various dates.

Books and articles

Baker, D. W. A. 1967. ‘Lang, John Dunmore (1799–1878)’. Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/lang-john-dunmore-2326/text2953, accessed online 3 February 2023.

Boland, T. P. 1986. James Duhig. St Lucia: University of Queensland Press.

Broome, Richard. 1980. Treasure in Earthen Vessels: Protestant Christianity in New South Wales Society, 1900–1914. St Lucia: University of Queensland Press.

Buch, Neville and Beryl Roberts. 2016. A Quest for a Fair Go: A History of the Knights of the Southern Cross Queensland 1921–2015. Stafford: Knights of the Southern Cross Queensland.

Campion, Edmund. 1987. Australian Catholics: The Contribution of Catholics to the Development of Australian Society. Melbourne: Viking.

Carey, Hilary. 2011. God’s Empire: Religion and Colonialism in the British World, c.1801–1908. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Costar, Brian. 1981. ‘Labor, Politics, and Unemployment: Queensland During the Great Depression,’ PhD thesis, Department of History, University of Queensland.

Costar, Brian. 2003. ‘Vincent Clair Gair: Labor’s Loser.’ In Denis Murphy et al. (eds), The Premiers of Queensland. St Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 268–84.

Elliott, Laurence. 2013. ‘Religion and Sectarianism in Ulster: Interpreting the Northern Ireland Troubles.’ Religion Compass 7.3: 93–101.

Evans, Raymond. 2007. A History of Queensland. Melbourne: Cambridge University Press.

Fox, S. K. 1980. ‘The Protestant Labour Party.’ In D. J. Murphy et al. (eds), Labor in Power: The Labor Party and Governments in Queensland, 1915–1957. St Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 432–44.

Kildea, Jeff. 2002. Tearing the Fabric: Sectarianism in Australia, 1910–1925. Sydney: Citadel Books.

Lang, J. D. 1864. letter to the Brisbane Courier, 29 September, p.3.

Loyal Orange Institution of Queensland. 1907. Laws and Ordinances of the Loyal Orange Institution of Queensland. Brisbane: Loyal Orange Institution of Queensland.

Maguire, John. 1990. Prologue: A History of the Catholic Church as seen from Townsville, 1863–1983. Toowoomba: Church Archivists’ Society.

McVeigh, Robbie and Bill Rolston. 2021. Ireland, Colonialism and the Unfinished Revolution. Belfast: Beyond the Pale Books.

Murphy, D. J. 1980a. ‘Organization, Structure and Finance.’ In D. J. Murphy et al. (eds), Labor in Power: The Labor Party and Government in Queensland, 1957–1957. St Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 3–60.

Murphy, D. J. 1980b. ‘The 1957 Split: “A Drop in the Ocean in Political History”’ in D. J. Murphy et al (eds), Labor in Power: The Labor Party and Government in Queensland, 1915–1957. St Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 481–525.

Norman, E. R. 1968. Anti-Catholicism in Victorian England. London: George Allen and Unwin.

Queensland Irish Association. 1924. Rules and By-Laws. Brisbane: Moreton Printing Company.

Sullivan, Rodney and Robin Sullivan. 2013. ‘Archbishop Duhig and the Queensland Irish Association: exploring connections.’ Journal of the Australian Catholic Historical Society 34: 44–55.

Sullivan, Rodney and Robin Sullivan. 2023. A Hundred Thousand Welcomes: The History of the Queensland Irish Association. Brisbane: Boolarong Press.

Vaughan, Geraldine. 2022. Anti-Catholicism and British Identities in Britain, Canada and Australia, 1880s–1920s. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Zinn, Christopher. 1999. ‘Gerry Adams assailed by family of IRA victim’, Irish Times (Dublin), 24 February, https://www.irishtimes.com/news/adams-assailed-by-father-of-ira-victim-1.156151, accessed online 18 April 2023.

Related articles