Singing the Lord’s Song at St John’s Cathedral, Brisbane

Music is central to the identity and expression of Anglicanism in Queensland. At St John's, a musical culture has evolved from early colonial efforts to exactly replicate English models of choral worship to recent negotiations of English heritage and contemporary Australian idioms, with trailblazing musicians including the first female master of cathedral music in the British Empire.

By Marcus K. Harmes

This is a 15 minute read, published June 2024.

To ‘sing the lord’s song in a strange land’ is a lament from the 137th Psalm, when exiles from Jerusalem rhetorically wondered how they would worship God in Babylon. The sentiment may apply also to musicians who were trying to recreate in Brisbane the musical traditions of the great English cathedrals. On the other side of the world, church musicians did indeed have to sing the lord’s song in a strange land.

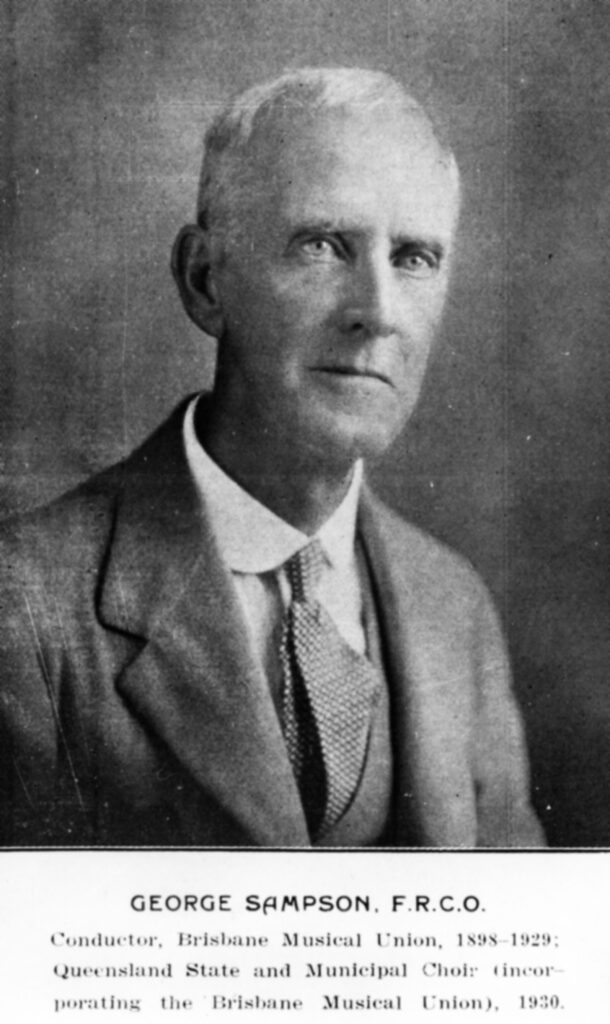

The music makers at St John’s Cathedral in Brisbane reveal fascinating tensions between different ways of being Anglican, being in the British Empire, and being gendered. The exceptionally long tenure of George Sampson, who arrived to play the organ and conduct the choir of Brisbane’s pro‑cathedral in 1898 and only retired a year before his death in 1948, shows an Englishman determined to create a colonial imitation of English cathedral music. His successor Miss Louise Grimes offers a more complex impression of Anglican music in the colonies. Her career making music was simultaneously counter cultural and firmly entrenched in the imperial and Anglican establishment of the 1950s. In her time Grimes was the only female cathedral music director in the British Empire, a novelty discussed in the press and sufficiently unusual to be remarked on by visiting dignitaries. But her counter-cultural presence as a lone female among cathedral music masters around the globe is only one part of her story. As organist until 1960, she conducted and performed when St John’s was the gathering point for the proud subjects of the British Empire. Her music was of and for the establishment, and even Queen Elizabeth II was once in her congregation.

Anglican music in colonial settings

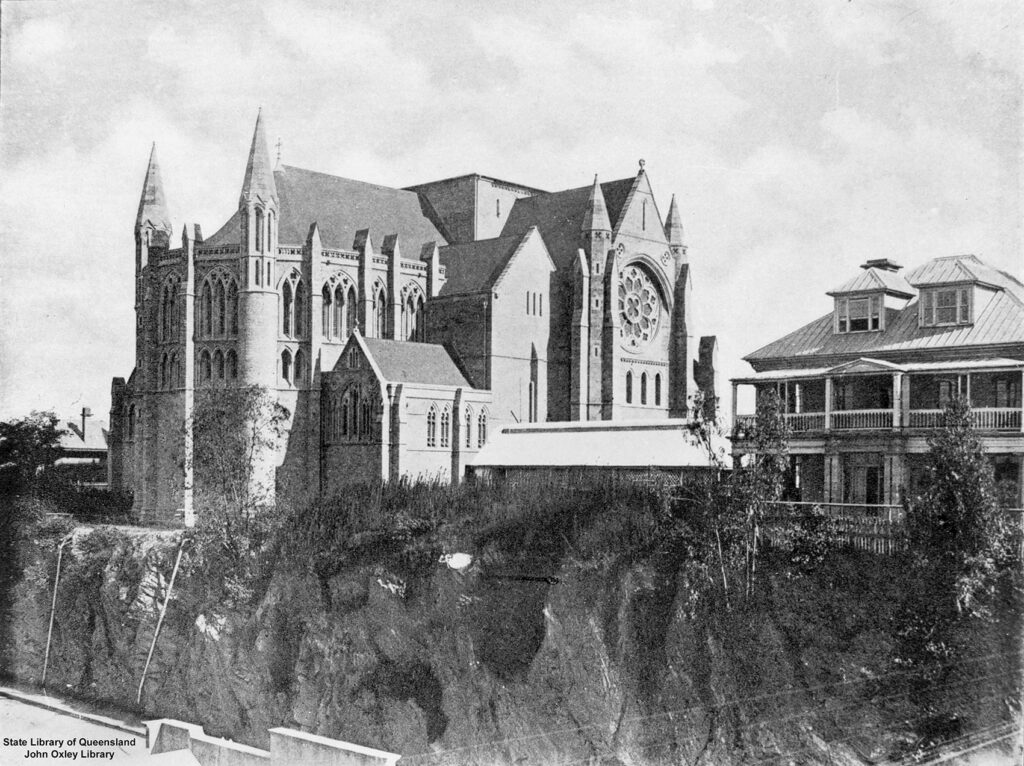

The centre of Queensland’s Anglican religious activity is St John’s Cathedral in Brisbane. The intentions of the cathedral’s builders — not only those who physically constructed it but members of the Church and society who inspired and funded it — was to create in colonial Brisbane a replica of an English cathedral. The architect John Pearson was English as was the bishop, William Webber, who commissioned its design.

The creation in Brisbane of the physical fabric of a gothic cathedral and the less tangible liturgical and musical fabric of choral music in worship has many colonial analogues. By the turn of the 20th century, many cities in Australia had a stone-built cathedral with organist, choir, and a round of daily worship emulating English cathedrals. Since the Middle Ages and throughout even the religious changes of the 16th and 17th centuries called the Reformation, English cathedrals maintained musical establishments offering organ and choral music for worship (Smith, 1967–68: 38–41). More broadly still cathedrals in the British Empire and in post-revolutionary North America consciously followed the style and repertoire of English cathedrals, not only singing English music but often bringing organists and choir directors from England to transplant the standards and style of English religious music to new settings (Ogasapian, 2007: 155).

These intentions matched the ambitions of choir masters throughout the Empire. While the walls of new cathedrals rose in colonial cities, with designs mimicking medieval structures in England, the services within these buildings looked and sounded English. Near universal use of the 1662 Book of Common Prayer (or its 1789 post-revolutionary iteration in the US) ensured conformity in the structures, words, and expression of public worship. The creative intention to establish English-style choirs singing English music, often accompanied and conducted by English musicians, also ensured consistency in how worship was enacted in the Empire, the Commonwealth, and anywhere there was English cultural influence. For example, St George’s Cathedral in Cape Town, South Africa, maintained a choir of men and boys directed by the Englishman Thomas Dowling and sang a conservative repertoire of English music (Bethke, 2016: 5). J.G. Ballard’s novel Empire of the Sun includes sequences set in the choir school of Holy Trinity Anglican Cathedral in Shanghai, based on Ballard’s early life when he had sung in the cathedral choir before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor (Ballard, 2005: 3, 6).

Figure 2: Interior of St John's Anglican Pro Cathedral, Brisbane, 1889 (State Library of Queensland).

The emphasis here on cathedrals should not obscure that English religious music was not and is not a homogenous entity. Rather, it has had different characters contingent on context and scale. English parish churches maintained musical traditions of their own. These traditions included metrical psalmody using mixed voice choirs accompanied by a band, both situated in a west gallery, rather than an organ accompanying a choir of boys and men located in the choir stalls of the chancel, or the eastern section of a church (Rainbow, 2001: 269). Alongside the cathedral in Brisbane, Anglican church music has been and continues to be heard in many hundreds of parish churches. As shown in histories of church organs (Organ Historical Trust of Australia), many churches acquired a pipe organ, the first in Queensland being at St Paul’s Ipswich (Boughen, 1974: 12; Pender, 2007: 80). Music in their worship could vary, from attempts to imitate the scale and quality of cathedral music to the simpler music characteristic of parochial worship.

For cathedral worship, a revival of standards in English religious choral music in the 19th century also influenced colonial endeavours. A generally low standard prevailed cathedral music during the 18th and early 19th centuries. The broader patterns of worship and doctrinal and ritualistic changes broadly associated with the Oxford Movement encouraged both statelier services and a higher standard of singing not just in England but around the global Anglican Church (Nicholls, 2017: 24). These different characters of music, cathedral and parochial, and these shifting and rising expectations, were precedents which manifested in colonial Anglican music making. The demarcation in repertoire and approach between a cathedral and a parish church generally prevailed in Australian , not least as cathedrals generally had larger resources to maintain a more elaborate musical establishment.

Colonial Australian cathedrals also generally maintained the pattern of services that English cathedrals had adopted by the middle of the 19th century, which were matins and evensong most days, and a celebration of Holy Communion together with matins and evensong on Sundays (Cameron, 2014: 53).

Cultural and social Englishness

Into the complex cultural framework of late colonial Brisbane stepped George Sampson, an English-born and trained composer and organist who arrived in 1898 to direct the music in the as yet unbuilt Anglican cathedral (Brisbane Courier, 2 April 1898: 6). It was a complex cultural framework for several reasons. Cathedrals throughout the Empire were typically led by English clergy and musicians who were determined to establish and maintain both an English pattern and an English standard of choral worship. Yet these ambitions were often confounded by colonial conditions. A musician such as Sampson, therefore, faced the reality of making English music in ways that followed but often failed to meet a clearly articulated benchmark. There had of course been music in Anglican churches since at least 1848, well before Sampson’s arrival (Boughen, 1974: 2; Gome, 1996: 157). Bishop Tufnell encouraged his congregations to use a hymn book, and organists R.T. Jefferies, J. Vigden, Madam Mallalieu and Miss Henrietta Gilder led music at the pro-cathedral (Boughen, 1974: 22, 43, 49). However, historian Keith Rayner notes these early efforts were still often crude and limited (1962: 63).

Before arriving in Brisbane, Sampson had not in fact been a cathedral choir master. While he was a fellow of the Royal College of Organists, he exercised his profession only in parish churches and as a school master (Crouchley, 1988). It is tempting to speculate that Brisbane appealed because of the offer of a cathedral position unobtainable in England, though the cathedral was only in the planning stage. The first section of St John’s rose between 1901 and 1910, but the cathedral was not completed until 2009, long after Sampson’s death in 1949. Incompleteness had musical implications. Sampson neither performed nor heard music in the completed building. The pipe organ he had requested arrived smaller than Sampson had specified. The instrument provided by the English firm Norman and Beard contained only 23 stops of the 50 Sampson had envisaged, but which cost too much for the cathedral authorities. The cathedral organ would grow stop by stop as benefactors gave money (Church of England, 1927: 147).

As the first stage of the new cathedral took shape, Sampson’s instructions to the organ makers in England was for a full-scale organ that would one day be worthy of a large and completed cathedral: ‘The whole scheme of the organ to be full cathedral scale and designed for a large and lofty building’ (Cox, 1989: 11).

Before the construction of the first section of St John’s Cathedral (which started in 1906), Sampson directed music in the pro-cathedrals of St John’s (demolished in 1904 and on the site of Queen’s Gardens in William Street) and St Luke’s from 1904 to 1910. Sampson was dismayed by his working realities. St John’s pro-cathedral itself was far removed from English cathedrals in scale and Sampson thought the building was a ‘freak’. Its pipe organ was limited and restricted the type of music he could perform, and even gave him ‘broken finger nails and strained muscles’ when playing it. The singers were not of the type Sampson wanted or expected; namely, they included women (Sampson, n.d., n.p.).

Figure 4: An incomplete St John’s Cathedral rising up behind the advertising hoardings in Queen Street, c. 1908 (State Library of Queensland).

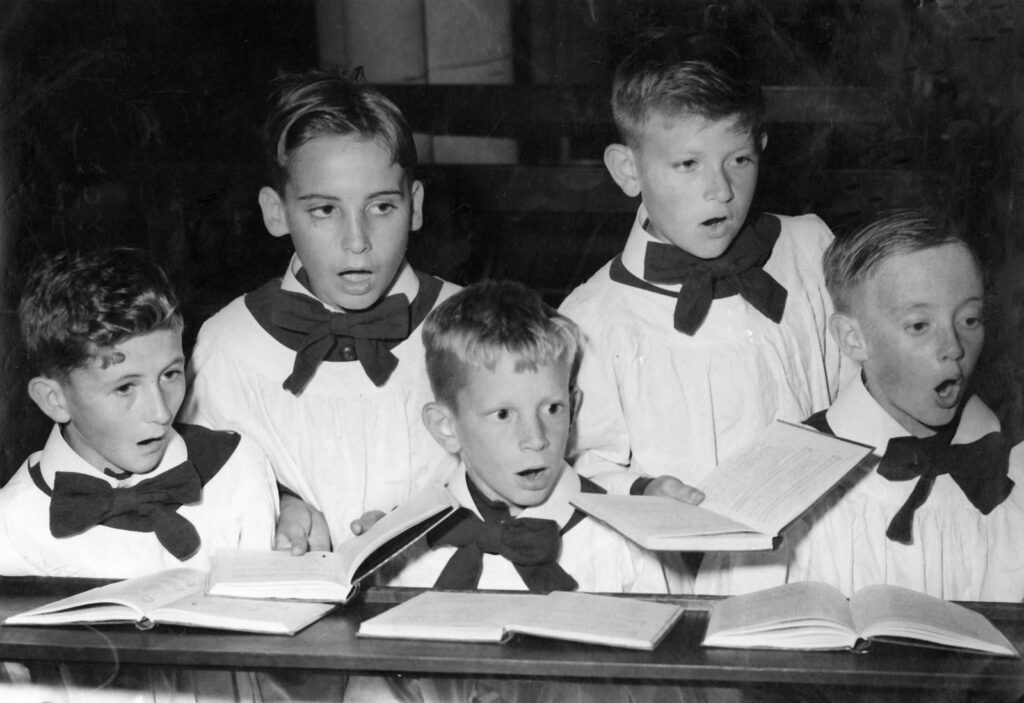

English cathedrals only began to recruit female choristers in the 1990s. The centuries-old tradition of English cathedral choirs involved the education of a boys in a song school or choir school attached to the cathedral; the boys consequently sang in the cathedral choir. Sampson thus inherited and was acculturated to a highly specific set of cultural expectations about not only what was performed in divine service but also by whom it was performed.

Figure 5: Choir boys practising at St John's Cathedral, Brisbane, 1958 (State Library of Queensland).

Records of pro-cathedral services show Sampson performing a repertoire largely taken from his Victorian contemporaries but with the soprano line of his choir comprising some boys but also women. Notes compiled by Sampson’s wife and held in the Anglican Diocesan Archives document his intention to ‘have at St. John’s a replica of an English Cathedral Service’. Bit by bit Sampson built his replica of English worship. The final service at the pro-cathedral took place in August 1904, and the music and those performing it capture Sampson’s ambitions at a point of transition from his early compromises to his fuller vision for English-style worship in a cathedral. The music included settings of the evensong canticles the Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis set by the British composter Garrett and choir boys singing in the standard cathedral disposition of being divided between cantoris and decani. However, there were also a large proportion of women singing as well (Addison, n.d.: 29). This practical reality conflicted with his ambitions.

Determined that ‘women must go’, Sampson reformed the choir to be all-male. He also expanded the music library to give the choir a repertoire and established infrastructure to support his choir and its performances. That included founding a choir school to train and educate the choristers. As ever, his benchmark was England and the notes made by his wife characterised his ambition for ‘a Choir School in true Cathedral tradition’ (Sampson, n.d., n.p.). Stable infrastructure therefore provided a stable platform for cathedral worship that would replicate an English model, in particular daily singing at evensong in the cathedral.

If the valedictory service at the pro-cathedral in 1904 presents a historical snapshot of Sampson at a point of transition, a surer sense of replicated English worship is conveyed by accounts of the consecration of the new cathedral in 1910. According to the Telegraph, a three-hour service featured ‘rich music which floated down from the organ loft’. The same report was sensitive to the impact of music, noting the profound effect of ‘intense silence, which was broken by the organ bursting forth and the choir’s singing “Veni Creator Spiritus,” to Attwood’s setting’ (29 Oct 1910; 2). Yet still there was compromise, the report noting that solo passages in the music were sung by women sopranos.

Female leadership and novelty

Sampson retired in 1947. During his tenure he moved from a pro-cathedral to a real cathedral, acquired a large organ from England, and created a choir and a choir school. For Sampson, having women sing in his choir was unacceptable and he devoted considerable efforts to building up a choir of men and boys. However, having a woman preside from the organ loft and direct the choir was another matter and after Sampson came the irony and oddity of his cherished all-male choir now being led by a woman. Towards the end of his tenure he received musical assistance from Miss Louise Grimes, an organist and musical educator who was also a broadcaster on the Australian Broadcasting Commission and a member of the music committee for the state’s Department of Public Instruction. In 1947, Grimes made history in terms of Anglican cathedral music. Following a competitive process, she defeated 18 male candidates to become organist and master of the choristers at St John’s (Courier Mail, 8 May 1947: 5; Truth, 3 July 1949: 34; Australian Women’s Weekly, 15 Oct 1949, 29).

Grimes served the cathedral for 12 years from 1947 to 1960 yet has been somewhat forgotten between two longer-serving male organists, Sampson, and then Robert Boughen, the cathedral’s musical director from 1960 to 2005. By 1947 Grimes was already a trail blazer as the first woman from Queensland to graduate from Adelaide University with a Bachelor of Music (Telegraph, 24 Nov 1937: 22). She was also unique in the global Anglican Church. The Archbishops of York and Canterbury (the two most senior leaders of the Anglican Church) both informed her that no other Anglican cathedral in the Empire had a woman directing the music (Courier Mail, 31 March 1954: 8).

The Queensland press often emphasised the novelty of having a woman choir master. The Courier Mail reported, ‘Miss Grimes sits in flat heeled shoes to play the £30,000 organ. High heels catch in foot pedals, [and] make for inaccurate chords’ (31 March 1954: 8). Fashion rather than music was also the emphasis in the Sunday Mail, which described her as a ‘slight wavy-haired woman in a light summer frock’ (28 Nov 1954, 13). Accounts in fact constructed a multifaceted impression of her. Alongside reports noting her domestic skills in making ice cream for her choir boys, were pictures of her in academic gown, hood, and trencher, reinforcing her qualifications from the Universities of Adelaide and Queensland. These incidental details of dress and cookery arguably would have no place in accounts of male choir masters. Throughout her tenure Grimes remained something of a novelty in combining the musical, academic, domestic, and womanly in ways that could sometimes be trivialised, but which also continued to suggest the significance of Brisbane having the only female master of choristers in the Anglican Church worldwide.

Grimes’ successor Robert Boughen unkindly described her as having ‘no particular reputation as a virtuoso organist’ and repeated an unsubstantiated description of her choral conducting being akin to a ‘that of a somewhat limited primary-school teacher’ (Boughen, 2007). These negative perceptions are not borne out by contemporary accounts of her music making, especially since she presided at a time when local newspapers reported in depth on church services and subjected them to detailed and critical review as though they were concerts. Indeed, Grimes merits attention for her progressive accomplishments for the musical life of the cathedral. She was praised for ‘an exacting and finely balanced programme’ (Courier Mail, 4 June 1949: 4) and the ‘ethereal quality’ of the choir boys’ voices (Courier Mail, 6 Dec 1947: 5). Grimes’ performance of Bach was notable for its ‘clean phrasing and unerring pedalling’ (Courier Mail, 10 June 1950: 6). Her Christmas services became major social events in Brisbane (Courier Mail 26 Nov 1947; Courier Mail 1; 22 Nov 1950; 3).

Almost nothing survives in audio recordings to let modern listeners judge the quality of her music for themselves. A short film made by Alan J. Campbell in the early 1950s is a brief and rare opportunity to hear Grimes’ choir. The choir boys are singing with a hooty-ness once characteristic of Anglican choirs but also with a full-throated vigour, and Miss Grimes is playing the organ at a steady pace as they sing the hymn ‘O God Our Help in Ages Past’ (Alan J. Campbell Motion Pictures, n.d.).

Boughen did credit an important aspect of Grimes’s tenure. In maturing and developing the choir repertoire and concerts, she ‘“dragged the Cathedral music screaming from the Victorian days into a more contemporary stream”’ (quoted in Hehir, 1989: 15). On her appointment Grimes gave an interview to the Courier Mail giving mixed views on music, expressing a love for Bach and that she appreciated a ‘number of modern compositions’ but found that ‘ultra-modern music is distressing’. By 1947, ‘ultra-modern’ music may have meant the serialism of Arnold Schoenberg or the modernism of Igor Stravinsky, but Anglican composers largely eschewed these (Courier Mail, 8 May 1947: 5). Among other composers, Grimes used Bach, Purcell, Attwood, Walford Davies, and Mendelssohn, conventional choices for an Anglican cathedral. Yet Grimes looked both backwards in time and to her modern contemporaries to find repertoire for her choir. Where Sampson mostly used Victorian music, Grimes gave her choristers medieval and Tudor music to sing (funding the purchase of the scores with cake stalls) but also premiered in Brisbane much more recent compositions, including by Benjamin Britten and Ralph Vaughan Williams, as well as music from far beyond her own Anglican musical traditions, such as Tchaikovsky (Friends of the Cathedral Newsletter October 1990, 4). Still, however, there was no Australian repertoire.

Emergent shifts in identity

Two English archbishops confirmed to Louise Grimes that she was the only female organist and master of choristers in an Anglican Cathedral anywhere in the British Empire. This frame of reference, the Empire, provides an important insight to understanding the action of Anglican music making in Brisbane from the colonial era onwards. Although there were and are multiple religious identities in Queensland, until well into the 20th century Anglicanism retained a special status as the faith of the monarchy, of the majority of the population, and as the expression of religious identity tightly bound up with imperial identity. Many senior clergy including Sir Reginald Halse, Archbishop of Brisbane from 1943 to 1962, came from England, as did the state governors. St John’s was where boys and girls came for Empire Youth Sunday and where the governor, the military, the judiciary and the municipality came for special services. The influence of Anglicanism in public life was not absolute. Vince Gair, premier until the Labor Party split of 1957 and his expulsion, was a Roman Catholic as were many members of his cabinet and the Chief Justice Neal Macrossan (Lack, 1960: 629). However, Gair’s successor as Labor leader, Leslie Wood, was Anglican, as was the Governor Sir John Lavarack, and the Anglican Church was the state’s largest denomination (Rayner, 1962: 280; Harmes, Harmes and Harmes, 2012: 626).

These links of Empire, monarchy, Anglicanism, and the local Brisbane community were especially asserted when Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip worshipped at St John’s on March 10th in 1954, one of the many civic events they attended in Queensland that month (Visit to Queensland, 1954: 36). filled the cathedral (still only half built) with more outside. Miss Grimes, the cathedral choir, and the cathedral organ singing a setting of the ‘Te Deum’ (Brisbane Telegraph, 10 March 1954: 4).

On the cusp of the Queen’s visit, the Kinetone production by John J. Campbell wove together the themes of the Church, the Empire, the Monarchy, and Brisbane. Pride that Brisbane was growing up as the First City of the Commonwealth was tempered by the shame that the city’s Anglican Cathedral was still half built. Yet even half built, the cathedral was where according to Campbell, could come together. The same production acknowledged that soon the Queen would visit this incomplete structure and urged that completing it would be a ‘fine gesture’ showing Queenslanders’ loyalty to the young monarch. The production explicitly likened the choral music in St John’s to the musical traditions of Westminster Abbey, which an enormous global population had just seen in the televised Coronation of Elizabeth (Harmes, Harmes and Harmes, 2020: 19).

Figure 9: Crowds gather to see Queen Elizabeth II near St John's Cathedral, Brisbane, 1954 (State Library of Queensland).

St John’s remained incomplete until 2009. In the decades following the Queen’s visit in 1954 the choir of boys and men continued to provide music at the services. A new dean arrived from England, as often was the case with the Church of England in Queensland, and he replaced Miss Grimes with Robert Boughen (Mackenzie-Smith, 2007: 334). Some changes were profound. In 1978 An Australian Prayer Book supplemented and often replaced the Book of Common Prayer in Anglican worship. Service patterns changed with a celebration of the Eucharist becoming normative and sung matins less common, changing the baseline of the repertoire from the canticles of the Te Deum and Jubilate familiar to generations of both churchgoers and church musicians to a setting of the Ordinary of the Mass created by an international ecumenical commission. Yet the repertoire also remained largely intact. In 1980 the cathedral choir released an LP of choral music including Purcell, Gibbons, Howells, and Bach, works used by Grimes from decades earlier. A choir library catalogue from 1996 in the cathedral archives is full of many standards any cathedral choir would sing (Choir Library Catalogue, 1996).

There is also considerable irony that women are back, ironic in the sense that Sampson strove so energetically and forthrightly to banish women from the cathedral choir and build a choir of boys and men. While there is still the treble line of boys that Sampson so cherished, music at St John’s is now characterised by diversity. A girls’ choir, a mixed voice chamber choir, and the foregrounding of contemporary Australian music are aspects of the musical culture in the cathedral (‘Music’, n.d.). These are not necessarily points of departure from the sound world and cultural expectations of Sampson and Grimes, as both presided over change as well as continuity, but they suggest how enacting musical identities continues to modulate in new directions.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Michael Rogers, Diocesan Archivist, Records and Archives Centre, for invaluable assistance with cathedral records.

Sources and further reading

Addison, K. n.d. Historical and Archival Notes. Brisbane: St John’s Cathedral.

Alan J Campbell Motion Pictures. n.d. Queen’s Visit Appeal. State Library of Queensland. accessed online 19 June 2022. www.youtube.com/watch?v=S0s5LhvbOeA.

Ballard, J.G. 2005. Empire of the Sun. Simon and Schuster.

Bethke, A.J. 2016. ‘Music in the South African Anglican Diocese of Cape Town from 1900 to the Present: Toward a History of Anglican Music in the Anglican Church of Southern Africa.’ Yale Journal of Music and Religion 2, 1: 1–24.

Boughen, R.K. 1974. ‘An Account of the Music at St. John’s Cathedral Brisbane from 1843-1887.’ Masters thesis, University of Queensland.

Boughen, R.K. 2007. ‘Grimes, Louise Catherine (1907–1990).’ Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, accessed online 19 June 2022. https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/grimes-louise-catherine-12568/text22629, published first in hardcopy 2007.

Cameron, N.M. 2014. ‘Music of the Anglican Cathedral and selected Anglican parish churches of the diocese of Sydney 1869–1940.’ PhD Diss., Macquarie University.

Church of England. 1927. Year Book of the Diocese of Brisbane. Brisbane: R.S. Hews and Co.

Cox, G. 1989 (October). ‘The Organ of St John’s Anglican Cathedral, Brisbane.’ Organ Society of Queensland, 6–13.

Crouchley, B.1988. ‘Sampson, George (1861–1949).’ Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, accessed online 19 June 2022. https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/sampson-george-8332/text14619, published first in hardcopy 1988.

Gome, D. 1996. ‘Hymnody in the Australian Colonies, 1788–1901: a preliminary investigation of sources and functions of hymns.’ Australasian Music Research 1: 141–66.

Harmes, M. A., M.K. Harmes and B. Harmes. 2012. ‘Power at the Periphery: Sectarianism and the 1957 Labor Party Split in regional Queensland.’ Queensland History Journal 21, 9: 626–40.

Harmes, M., M. Harmes and B. Harmes. 2020. The Church on British Television: from the Coronation to Coronation Street. London: Palgrave.

Hehir, M.J. 1989 (October). ‘Cathedral Organist Profile: Robert Keith Boughen, O.B.E.’ Organ Society of Queensland, 14–17.

Lack, C. 1960. Three Decades of Queensland Political History. Brisbane: Government Printer.

‘Louise Grimes A Tribute to her Memory: Cathedral Organist 1946–1959.’ Friends of the Cathedral Newsletter October 1990, 4.

Mackenzie-Smith, J. 2008. ‘Dean WP Baddeley in Brisbane, 1958–1967.’ Journal of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland 20, 7: 321–36.

Ogasapian, J. 2007. Church Music in America, 1620-2000. Macon: Mercer University Press.

Rainbow, B. The Choral Revival in the Anglican Church (1839-1872). Boydell and Brewer.

Rayner, K. 1962. ‘History of the Church of England in Queensland.’ PhD thesis, University of Queensland.

Saint John’s Cathedral. 1996. Cathedral Choir Library Catalogue.

Saint John’s Cathedral Website. n.d. ‘Music’. Accessed online 18 July 2022. www.stjohnscathedral.com.au/music/

Sampson, A. n.d. [1943?]. ‘Forty Five Years of Cathedral Music.’ Unpublished.

19 June 2022. https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/webber-william-thomas-thornhill-9027/text15897, published first in hardcopy 1990.

Smith, A. 1967–68. ‘The Cultivation of Music in English Cathedrals in the Reign of Elizabeth I.’ Proceedings of the Royal Musical Association 94th session: 37–49.

Visit to Queensland of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II and His Royal Highness the Duke of Edinburgh, Tuesday, 9th to Thursday, 18th March, 1954: Official Programme. 1954. Issued by F.A. Manning, State Director 1954 Royal Visit.

Related articles