Rev. Merrington and the ANZAC Memorial Peace Chapel at St Andrew’s

During the Great War, Rev. Dr E. N. Merrington served in Gallipoli and in France, his diaries describing mystical and sublime experiences. Returning to Australia between his posts, the Reverend helped establish Anzac Day in 1916. Many years later, St Andrew's Uniting Church established the Merrington ANZAC Memorial Peace Chapel.

By John Grimes

This is a 20 minute read, published in June 2024.

During the Great War of 1914–1918, Rev. Dr E. N. Merrington of St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church, Creek St., Brisbane offered himself as an army chaplain to the Australian Imperial Force. He served at Gallipoli (1915) and in France (1918). His war diary and letters home talk of numinous and sublime experiences, while his pre- and post-war writings speak of a ‘mystical urge’ and of ‘a loving heart’ as ‘the more excellent way’ of being guided in ethical and moral dilemmas.

More recently, in 1996, a Merrington ANZAC Memorial Peace Chapel (MAM Peace Chapel) was designated as a ‘memorial space’ within St. Andrew’s, which by then was a Uniting Church. It has a number of religious and historical features, including stained glass representations of Mary and John, a skull symbolising Golgotha, burning villages in France, and an ‘angel of peace’. The focal point is the communion set (a silver platter, cup, and tray) used by chaplain Merrington at Gallipoli in 1915 (BLHN, 2019)

These items were originally donated to the church by Merrington’s wife, Flora; later, it was suggested by others that they be used as part of a warriors’ chapel, a sacred place where war dead are mourned and remembered. There are also flags, honour boards, and lists of Great War servicemen associated with St Andrew’s Church, whose stories are also features of the Chapel.

Yet, how did a chapel dedicated to warriors become a peace chapel? And is it fitting that the memorial is named in association with the Rev. Dr Merrington?

Focus, feeling, and story

I propose to answer such questions through an analysis of the religious site, ritual, and story associated with the Merrington peace or warriors’ chapel, according to three guiding aspects: focus, feeling, and story. We shall consider each in turn.

Ninian Smart — renowned scholar of religion — suggests that the starting point for a phenomenology of religion (the study of religious feeling) is the need for a ‘rather heavy contextualization of religious utterances.’ That is, a consideration of all factors relevant to the object of analysis (Smart, 1973: 4–5) He also argues for attention to be paid to the focus of a rite, such as Christ in the Eucharist (Smart, 1973: 5–6)

Smart’s second point is that a theory and treatment of myth or religion (here the myth or story of Anzac) must assume the ‘numinosity’ or religious nature of the ‘divinities’ (i.e., the Anzacs), or at least of some of them in the stories (i.e., Merrington) who are themselves associated with any ritual or remembrance, past or present (Smart, 1973: 6)

So, what has this to do with our inquiry?

The first question then is this: what is the focus of the site (in the absence of a rite)? Second: what feeling, if any, does the chapel convey or evoke? And third: what is the story explicitly or implicitly on display? And what is its context?

With regard to the first, it would seem that the focus of the chapel is two-fold: on the one hand, Merrington’s wartime Communion (Eucharist) Set, and on the other the stories and memorialisation of the warriors, those connected to St. Andrews who took part in the Great War of 1914–1918.

Does one feel at peace or peaceful while in the peace chapel? Or does one perhaps feel another emotion: sadness or anger at the loss of life (perhaps of those on the honour boards surrounding the altar listing soldiers killed in action); or any number of other feelings or emotions, such as pride and thankfulness for the service and sacrifice given by others.

The explicit story and central focus of the Communion Set is that Christ died for us. The implicit message of the associated stories and memorialisation of the warrior servicemen is that they (also) died or suffered for us. That is, following Smart, there is a ‘rather heavy contextualization of religious utterances,’ or messages, on display for those who have eyes to see or ears to hear. As to the numinosity (sacredness, holiness, divine or heroic nature) of those who are the focus of the displays, once again, this is in the eye or the heart of the visitor or the believer.

A sacred place

According to Smart, ‘an important question for the philosophy of religion is the nature and ‘validity’ of the experience of the Holy,’ a view for which he was indebted to Rudolf Otto (Smart, 1973: 6) For Otto, das Heilige (the ‘holy’, ‘sacred’, ‘numinous’, ‘sublime’) is real and can be experienced. It exists along with the rational as an equal and a priori element of ‘the complex category of “holiness”’ and has its ‘own independent roots in the hidden depths of the spirit’ (Otto, 1959: 136). These were, and still are, fighting words in the contested and continuing debate as to the nature of transcendent or religious experience, since, according to Otto, religious and transcendent experience is unique (sui generis) and cannot be reduced to anything else.

To relate these insights to the MAM Peace Chapel, the nature of any experience a visitor to it might have can, depending on the individual experience expressed, be seen as transcendent, sublime, numinous, holy, or sacred. For St Andrew’s historian and archivist, Noel Adsett, the chapel is a ‘sacred place’ (BLHN). And as Rudolf Otto puts it, writing during the Great War itself, the holy is essentially an experience of the divine rather than a moral, religious idea or ideal.

So, is the chapel in question evocative of such a holy or sublime experience? And does it do justice to its namesake, Merrington?

Merrington’s spiritual journey

Ernest Northcroft Merrington was born in 1876 in Sydney NSW and received his secondary education at Sydney High School in the 1890s. As a child he regularly attended various church youth groups and writes in his memoirs that, ‘Although I did not make any public profession of my faith at the time, I have always felt that the spiritual change in my life occurred just then’ (Merrington, 1948: 11) The family, meanwhile, having become unhappy with the Congregational Church while at Glebe in the 1890s, had gone over to what Merrington’s memoirs describes as evangelical Presbyterianism.

He later gained a first-class BA Honours (Greek, Philosophy, English) with the University Medal and the Professorial Prize in Philosophy in 1900 and an MA Honours with Medal in 1903 from Sydney University. Prior to the Great War he was awarded a PhD from Harvard University, after first proceeding to the University of Edinburgh on a Woolley Travelling Scholarship.

Merrington admits to certain transcendent moments at key times in his life. One such occasion was his decision to enter a life of religious service, which came upon him one mid-October afternoon in 1896, not long after he had quit his job in the jewellery industry and moved with his family from their waterfront Sydney home. He wrote later about this moment, which can best be described as a sublime, religious experience similar to those reported by his Harvard University mentor, William James (Grimes, 2021). It was also the kind of experience that Caroline Franks Davis describes as nature mysticism, involving the ‘transfiguration of external things, as if they have suddenly been imbued with deep meaning or with a living force … guided by Love’ (Almond, 1982: 71–72; Franks Davis, 1989: 58) Merrington writes ( 1948: 17):

One evening … I was walking home across Ultimo, when the great decision of my lifework was made. The western sky was ablaze with golden light as the sun sank towards the hills. My heart was drawn out in more than adoration for the natural beauty, its depths were stirred with adoration for the great Creator. I suddenly felt the ‘call’ to serve God with my whole life.

Later, when he was living in Brisbane, Merrington described another ‘mystical urge’ during the Jubilee celebrations of St. Andrew’s congregation in August 1912. The celebrations were to include a Jubilee Communion Service, held with a ‘sacrificial’ thanksgiving offering; a vice-regal garden party; a Jubilee organ recital and a ‘special and beautiful’ souvenir booklet — the foreword emphasising the ‘spiritual background of the origin and growth of the Congregation’ (Merrington, 1948: 59).

While writing this foreword, Merrington was ‘moved to write a Hymn of Jubilee for the occasion, realising the great work of the pioneers of the Church, and the gratitude felt to God for His Providence’ (Merrington, 1948: 59). He writes that his heart was ‘filled with thankfulness’ for the founding of Emmanuel College at the University of Queensland and what it might mean ‘to the future of the lands of the South Pacific Ocean.’ ‘Conscious of a mystical urge,’ he found himself dwelling on the ‘eloquent words’ of the Rev. Thomas Mowbray M.A. regarding the building of the first church on Wickham Terrace in Brisbane. He then penned God of Eternity (Merrington, 1948: 59):

God of Eternity, Lord of the Ages,

Father and Spirit and Saviour of men.

Thine is the glory of times’ numbered pages;

Thine is the power to revive us again.

The hymn was written in Merrington’s study ‘off the verandah facing the sunny north.’ Such a setting arguably providing a creative atmosphere. Even so, his ‘mystical urge’ nonetheless sprang from ‘within’, his heart ‘filled with thankfulness’ inspired by an intense focus on his subject (Merrington, 1948: 59) According to Caroline Franks Davis, Merrington’s sense of religious revival (expressed in the fourth line of the verse) falls into a category of religious experience she terms ‘regenerative’ (Franks Davis, 1989: 44).

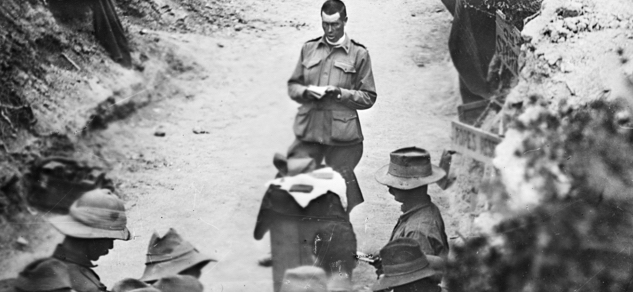

Merrington’s diary entry of 3 June 1915 when he was at Anzac Cove on the Gallipoli peninsula captures a similarly mystical tone. It reads: ‘The bullets were flying over the burial-ground like bees at swarming time while we walked about in view of the Turks a thousand yards away’ (Gladwin, 2013: 48–49). This, by any standard, he continued, was a strange situation for ‘a little prayer meeting’, a dugout on Pope’s Hill, Anzac Cove, that each night saw ‘some of the men gather there after tea, and as many as can get inside, while others squat around the entrance’ (Gladwin, 2013: 48).

For Merrington, the dugout itself was a kind of haven amidst a grim battle scene from which the strange and the beautiful could also be seen and felt. ‘I read a chapter of Scripture,’ he recorded, ‘and then prayer follows, concluding with the Lord’s Prayer, in which all join’ (Gladwin, 2013: 48). He added, ‘It is very strange and beautiful in these grim surroundings. We watch the lovely sunsets out at sea, over Imbros and Samothrace’ (Gladwin, 2013: 48).

Figure 4: Merrington conducting a communion service for 3rd Light Horse Brigade, Gallipoli, 1915 (Australian War Memorial).

Here, the aesthetic and the sublime, if not also the numinous, are experienced: ‘Sometimes we sing a well-known hymn, and the sound is wonderfully inspiring as it rolls down the valley’ (‘A Padre On Gallipoli’; Gladwin, 2013: 48). Momentary flashes of inspiration, insight, or revelation such as these are examples of Franks Davis’ fourth category of religious experience, ‘revelatory experiences’ (Franks Davis, 1989: 39). Not only were such experiences something to remember, they were also experiences that one needed to make sense of and to further describe (Merrington, 1916).

Lead on

Lead on, kindly, mystic light of God, it could be said, within these ‘grim surroundings’, a light of peace within the darkness of war. In such a setting, God was an experience ‘nearer’ to oneself, of oneself, ‘to thee’. As Merrington sang with others on the shores of Anzac Cove the hymns Lead Kindly Light and Nearer, my God to thee he had what could be understood to be a mystic experience of the divine. Merrington continues (Gladwin, 2013: 49):

The stars come out in the sky. The hillsides sink into darkness, somewhere the rifles flash on the crags, or a machine-gun starts into action, or a flare goes up over no-man’s land. Out at sea the forms of the ships become dark and indistinct. The hospital ship lights up her green band and brilliant red cross, which are reflected in the calm sea.

It was an experience of ‘light amidst darkness’, Merrington declared. ‘The red cross at sea is the symbol of the light of peace, love and hope in the darkness of this war’ (Gladwin, 2013: 48). While for Merrington the symbolism of the (red) cross no doubt chimed with his Christian worldview, the same symbolism — light amidst darkness and the triumph of light — can be found in many religious and mystical traditions.

Such symbolism and associated feelings of hope, peace, and love can also be understood, as Otto suggests, to spring ‘spontaneously’ from within, ‘even in cases where it is not … prepared for and sustained by a traditional cult and mysticism of “sacrifice”’ (Otto, 1959: 188).

Such an experience, explained by Merrington with reference to peace, love, and hope, can also be seen as a regenerative religious experience, which, if intense enough, can approach the mystical or the numinous, in Otto’s sense of those terms. This is perhaps especially true, as Franks Davis also suggests, if the experience is seen as being accompanied by ‘the sense of a divine presence‘ (Franks Davis, 1989: 45).

Anzac Day, 1916

By 1916, Merrington the chaplain had returned to Brisbane, and while back in Australia, amongst other patriotic, political, and religious interests and duties (including as President of the Returned Sailors’ and Soldiers’ Imperial League in 1917), he was an active member of the Queensland Anzac Day Commemoration Committee (ADCC), which grew out of the Brisbane Recruiting Committee. He also took an active part in and was the subject of sectarian, war-related, conscription and anti-Labour debates, as evidenced in various columns in local Brisbane and interstate mastheads, such as the Daily Standard (April 26, 1917), Worker (May 3, 1917) and The Catholic Press, Sydney (February 1, 1917).

He also spoke at the first civic Anzac Day event in Brisbane, held at the Exhibition Hall on the Tuesday April 25, 1916, which by all accounts was a solemn occasion. The evening began with organ solos by the City Organist, Mr George Sampson, playing March on the death of a hero by Beethoven, then Funeral March by Chopin. This was followed by the five verses of the hymn Nearer My God To Thee—the same hymn (along with Lead, Kindly Light) that Merrington had described in his June 3, 1915 Gallipoli diary entry as being ‘so impressive here that I am sure we shall never hear them in time to come without thinking of these scenes’ (Gladwin, 2013: 48–49) And sing them again, he did; and think about those scenes again, he did.

In speaking to the resolution of loyalty in the Exhibition Hall, The Telegraph recorded Merrington speaking of the Australian soldiers and sailors, ‘known now throughout the world as Anzacs’, who were ‘a most wonderful manifestation of human gallantry, grit and endurance’, and, quoting General Birdwood, ‘a spectacle of manly qualities’ which have ‘never been surpassed in the annals of arms’. Applause followed. Merrington added that if he could transport those assembled ‘in imagination’ below the ‘high ridges, shell pitted, and into those deep gullies, he would be enabling them to enter more fully into the meaning of the sacrifice of the gallant Anzacs’ (The Telegraph, April 26, 1916: 4).

At the morning service on the that very first Anzac Day, St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church was, according to The Telegraph, ‘thronged to the doors’, ‘many of the congregation being unable to obtain seating accommodation’. The front pews were reserved for returned soldiers and soldiers from Chermside and the nearby Exhibition camps, numbering ‘about 300 in all’. The Australian flag was ‘draped over the communion table’. According to The Telegraph reporter, ‘the service was affecting, and particularly returned soldiers visibly were labouring under emotion’. To the feelings of deep religious fervour and inspiring, soulful singing and prayers for divine love were added Merrington’s words of ‘fervent’ and ‘united’ tribute to ‘their comrades who fought so heroically and died so devotedly.’ Merrington also ‘drew a touching word picture of the burial of those dead,’ read the King’s message published that day, and said that ‘indeed the sacrifice of Gallipoli heroes was not, never was, and never would be, in vain.’ The message of the dead to the living therefore was ‘We died for you. We laid down our lives that the flag of freedom might fly high throughout the world’ (The Telegraph, April 25, 1916: 2).

Merrington concluded, ‘the congregation that day was placing a flower of memory on the rough graves at Gallipoli’. The organist played The Dead March; The Last Post sounded (The Telegraph, April 25, 1916: 2).

A tradition — if not a mythology — was born on that first Anzac Day.

Indeed, at the fourth meeting of the Anzac Commemoration General Committee (ACGC) held in the Premier’s office at 8 o’clock in the evening on 30 June 1916, the Reverend Dr Merrington, by now Moderator of the Presbyterian Assembly, moved ‘That steps be taken to make Anzac Day a national commemoration in such manner as may be decided hereafter’ (ACGC Minutes, June 30 1916). The seconder of the motion, Colonel A. J. Thynne, made the point that ‘the intention of the public meeting originating the observance was, that it should be a national observance, leaving the future method free as to mode year by year’ (ADCC Minutes, June 30, 1916).

From this moment of genesis, and continuing to the present, Anzac Day observances have evolved over time as a foundation myth and national legend that for some serves as an Australian or civil religion.

Peace Chapel or Warriors’ Chapel?

Warrior chapels are found elsewhere. In 1923, the Governor-General laid the foundation stone of one in the Anglican Christ Church Cathedral in Newcastle, NSW. It was to be a sacred space where loved ones lost during the Great War could be mourned, featuring specially created works such as a small bronze crucifix, a sanctuary lamp, candlesticks and vases for the altar, an alms dish, and a ‘Book Of Gold’, an illuminated register of the fallen from every parish in the diocese. These items contained gold and precious stones ‘made from jewellery donated by women of the Diocese — engagement and wedding rings of wives and girlfriends’ (Duncan, 2014). As such, it can be seen as a sacred, memorial space, closely linked to and deeply meaningful for the local parish.

By contrast, the Merrington Peace Chapel was created some time after the cessation of hostilities in 1918. It is centred on Merrington’s wartime communion set, religious symbols, and the stories of members of St Andrew’s congregation who fought during the Great War. But why was it created in 1996 and not in 1916 or immediately after the war? And should we consider it today as a Peace Chapel, or as a Warriors’ Chapel?

Figure 7: Merrington Memorial Peace Chapel, view from the nave (Matt Smith, Queensland War Memorial Register).

Part of the answer may lie in the fact that Merrington himself, who had always advocated on behalf of his charges, left St Andrew’s in 1923 to take up a position as Presbyterian minister in Dunedin, New Zealand, and did not return to Australia. It is interesting to note that at the February 1916 meeting of the St. Andrew’s Kirk Session (Elders’ meeting), Merrington, recently returned from Egypt and Gallipoli, had proposed that a service ‘of a memorial character’ be held in the church for those who had died ‘on the field’ and those who had died in Brisbane ‘during his absence’ (Kirk Session Minute Book, 1916). Discussion on the matter was deferred to the next meeting where it was decided that the service be held on ‘Anzac Day’, 1916.

Another part of the answer may well be that, as various historians of the Anzac tradition have noted, the Anzac myth and Anzac Day itself have gone through many iterations since the Great War — as Colonel A. J. Thynne and Merrington of the Queensland ADCC envisaged they should — and have been invested with different meanings over time: mateship, sacrifice, patriotism, and so on. Holbrook argues that by the time Prime Minister Bob Hawke visited Gallipoli in 1990, an Anzac revival was in ‘full swing’ (Holbrook, 2014). The St Andrew’s memorial to Merrington and the Anzacs was established in that context, and arguably then with an emphasis on peace, rather than war (and warriors) per se.

A third part of the answer involves the doctrinal differences with regards to prayers for the dead between Catholicism, Anglo-Catholicism (high church Anglicanism), and Presbyterian and Methodist (now Uniting Church) non-conformism, as John Moses points out in Anzac Day Origins (Moses and Davis, 2013: 167–69). Traditionally, Protestants, especially nonconformists, did not pray for the departed. Therefore, they are less likely to establish warrior chapels where prayers for the dead are said, even though, as Moses observes, ‘memorial services being held at the time [1915–16] in the Albert Street Methodist Church in Brisbane seemed to be doing precisely that’ (Moses and Davis, 2013: 168).

Yet, arguably, and in practice, it can be suggested that there is both a difference and a continuity between praying, mourning, remembering, and having feelings of peace that may take place or be experienced in a warriors’ chapel or a chapel of peace. Phenomenologically speaking, the experience can be the same or similar.

If, therefore, certain sublime or numinous moments are felt while in the MAM Peace Chapel, it could be suggested that they are not out of keeping with the setting and with that which it seeks to convey or evoke. Moreover, it can be further suggested that any such experience may well correspond to those timeless moments of peace and beauty Merrington himself experienced during the Great War.

Conclusion

Merrington experienced moments at Gallipoli that can best be described as sublime or numinous, involving feelings and the religious ideas of peace, love, hope, and light amidst the darkness of war. He had also been a key player in the Queensland Anzac Day Commemoration Committee, which established the civil and religious ceremonies of the first Anzac Day in 1916, leading to the creation of the ANZAC tradition.

More than a century later, the Merrington ANZAC Memorial Peace Chapel within St Andrew’s Uniting Church stands as a fitting memorial space honouring both Merrington’s memory and contributions and those of the original Anzacs.

Sources and further reading

Almond, P. C. 1982. Mystical Experience and Religious Doctrine: An Investigation of the Study of Mysticism in World Religions. Berlin: Mouton Publishers.

‘A Padre On Gallipoli.’ 2 AWM, PR 86/386, DPI 300.

BLHN. Brisbane’s Living Heritage Network, ‘Peace Chapel,’ podcast, 2019. (Interview with Noel Adsett.)

Duncan, C. 2014. ‘The Warrior’s Chapel — Christ Church Cathedral.’ ABC Local (online) April 23.

Franks Davis, C. 1989. The Evidential Force Of Religious Experience. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Gladwin, M. 2013. Captains of the Soul A History of Australian Army Chaplains. Newport, N.S.W.: Big Sky Publishing.

Grimes, J. 2021. ‘Anzac and the sacred: Australian religious experience and the Great War.’ Charles Sturt University, PhD Thesis.

Merrington, E. N. 1916. The Problem Of Personality A Critical And Constructive Study In The Light Of Recent Thought. London: Macmillan.

Minutes, Forth Meeting of the Anzac Commemoration General Committee, 30 June 1916 (signed and verified by Garland, 23 March, 1917), ADCC Correspondence, Box 20168 O/S, 45 JOL, Brisbane.

Minutes, 30 June 1916, ADCC Correspondence, Box 20168 O/S, JOL, Brisbane

Moses, J. A. and G. F. Davis. 2013. Anzac Day Origins Canon DJ Garland and Trans-Tasman Commemoration. Canberra: Barton Books.

Otto, R. 1959. The Idea of the Holy. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Smart, N. 1973. The Phenomenon Of Religion. London: Macmillan.

St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church Minute Book, Kirk Session, 22 February, 2 March, 1916, St. Andrew’s Church Archives, Creek St. Brisbane.

The Memoirs of Rev. Dr Ernest Northcroft Merrington, Foundation Chairman of Emmanuel College, Fryer MSS F3057, Manuscript, 1948.

Related articles