Creationism with an Australian Accent: From Queensland to the World

Many assume modern creationism to be largely an American phenomenon. But it has a strong Queensland flavour, both in the career of former schoolteacher Ken Ham, and the political and education controversies of the 1970s and 1980s.

By Tom Aechtner

This is a 20 minute read, published June 2024.

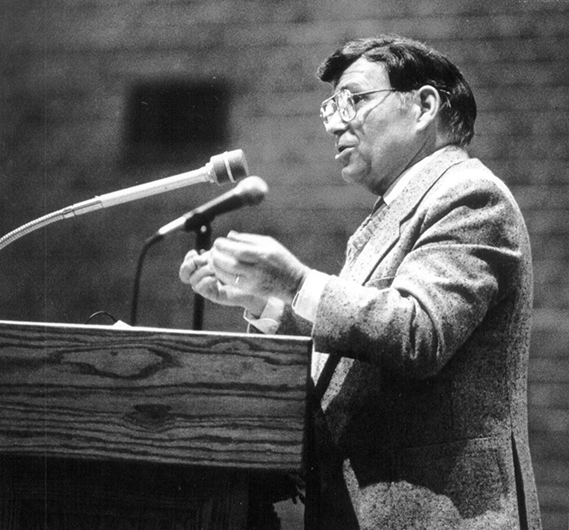

In 1977, a Queensland science teacher named Ken Ham teamed up with fellow educator John Mackay in Brisbane, to coordinate what has been described as the “first major creation seminar in Australia” (Ham, 2012a: n.p.). These two Queenslanders were part-time Christian speakers, who, when not in classrooms teaching, sold American creationist materials to local churches and schools (Harrison, 2004, p. 191). From these humble beginnings, Ham would go on to establish Answers in Genesis (AiG), the largest and most notorious young earth creationist organisation in the world.

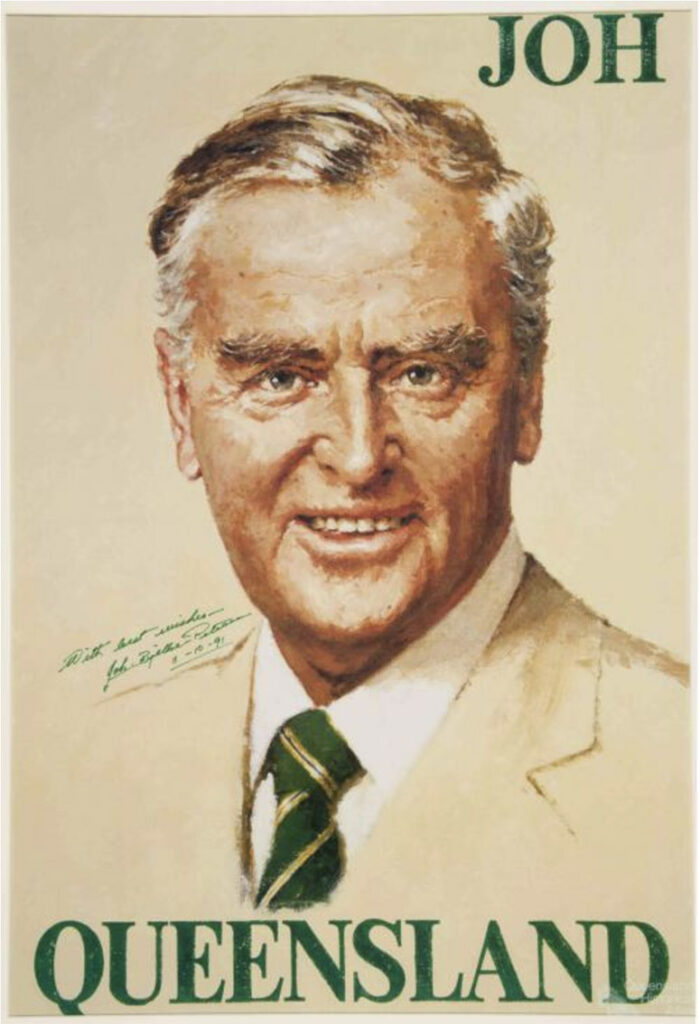

While AiG is now headquartered in Kentucky, USA, its origins can thus be traced back to Queensland. It was in Queensland that Australian creationism thrived during the 1970s and 80s under the longstanding premiership of Joh Bjelke-Petersen, whose Minister of Education Lin Powell expressed the view that Christian antievolutionism should be taught in Queensland’s high schools. Consequently, while creationism is commonly thought to be an American religious phenomenon, Queenslanders have played a substantial role in fostering Christian antievolutionism within Australia and abroad. This is the story of how creationism with an Australian accent spread from Queensland to the rest of the world.

Brisbane Creationism: Schisms and Exportation

Christian young earth creationism is a religious movement that accepts five central principles:

1. The age of the universe is between 6,000 to 10,000 years.

2. Noah’s flood, as detailed in the Bible, is responsible for producing most of the fossils found in the Earth’s geological layers.

3. Biological evolution from inorganic molecules to humans did not occur.

4. God created specific ‘kinds’ of animals that may have changed over time but did not evolve into entirely new species.

5. The theory of evolution is simply false, atheistic guesswork that stands in direct opposition to Christian theism (Roberts, 2008: 167).

These premises are based on literalist interpretations of the Bible, through which the Book of Genesis’ creation narrative is accepted as historical fact and taken to be a scientifically accurate account of the universe’s origins. However, while this specific variety of Christian creationism is what Queensland would later become known for, opposition to evolutionary theory in Australia was not originally opposed to the idea of an ancient earth. Instead, the first organised Australian community of antievolutionists, founded in 1947, was the local wing of Britain’s Evolution Protest Movement (EPM) (Numbers, 2002: 1–2). Though the EPM resisted evolutionary theory, it did not advocate for a specific interpretation of the Genesis narrative. It also did not initially support many of the central notions about Noah’s flood and the age of the universe championed by young earth creationists like Ham and Mackay.

Nevertheless, in the 1970s, Australian antievolutionism shifted towards the more literalist, recent creation model. This move coincided with an Australian tour by the American young earth creationist Henry M. Morris in 1973, and a visit by the likeminded Duane Gish in 1975. Young earth creationism would then come to characterise much of Australian creationism, with the antievolutionist movement being primarily centred in Queensland in the decades that followed.

While Ham and Mackay were spreading young earth creationism in Queensland, the South Australian physician Carl Wieland founded the Creation Science Association (CSA) in 1977. This institute, located in Adelaide, was Australia’s first official young earth creationist organisation, which began publishing its Ex Nihilo magazine the following year. After Ham resigned from teaching in 1979, he and Mackay joined forces with Wieland, merging their efforts in 1980 to form the Creation Science Foundation (CSF). Headquartered in Brisbane, the CSF would go on to serve as Australia’s foremost antievolutionist organisation. However, despite their initial cooperation, Ham, Mackay, and Wieland’s alliance would be disrupted by infighting and legal battles. The first of these disputes can be traced back to 1987, when Mackay rather bizarrely accused Ham’s personal secretary, Margaret Buchanan, of being a witch who engaged in necrophilia and attended “seances and satanic orgies” (Trollinger & Trollinger, 2016: 10). In due course, the CSF would push Mackay out of his role as a CSF co-director, with his place taken by Wieland, the man who would go on to marry the alleged ‘witch’ herself.

In the same year that Mackay made his peculiar accusations, Ken Ham published The Lie: Evolution, which would go on to become his most well-known book. 1987 also marked Ham’s relocation to the United States to work at the Institute for Creation Research, founded by Henry M. Morris, who had visited Australia the previous decade. Importantly, Ham travelled to the USA because the Christian Science Foundation in Brisbane felt that the American creationism formula expressed by Morris was lacking and in need of improvement (Aechtner, 2021: 128). Australian creationists believed that their American counterparts had focused too much on the apparent scientific proofs supporting creationism, rather than the scriptural foundations of the young earth stance.

In the US, Morris’s creationist approach was very much concerned with imitating science and its practices, while claiming that scientific data fully supported its conclusions. This involved attempts at demonstrating the validity of a young earth reading of Genesis from an allegedly scientific starting point. It was argued, therefore, that Christians could essentially begin with empirical data and scientific facts to demonstrate the truth of the Bible as read through literalistic perspectives. The Australians, on the other hand, tended toward a slightly different perspective. Though the CSF also sought validation for creationism from purported scientific evidence, they commenced more candidly from the standpoint that the literal Genesis account of creation was true because it was divine testimony (Aechtner, 2021: 129).

These slightly different creationist angles may not seem particularly significant. Yet in the 1980s, the Australians thought that the American position required some correction, and Ham was sent as a missionary to remedy the problem (Aechtner, 2021: 128). Then, in what would likely have been interpreted as a confirmation of the Creation Science Foundation’s slant, Ham drew impressive crowds in the USA at his lectures for the Institute for Creation Research. When Ham addressed American audiences, he focused less on scientific research and technicalities, and more on the message of the Bible and literalist interpretations of its creation narratives. Ham also placed more emphasis on the apparent evils that belief in evolutionary theory has caused, while Ham concentrated on the religious principles of fundamentalist, or ‘true’ Christianity.

In this context, evolution and Christianity were framed within a culture war between atheistic secular humanism on one front, and genuine Christian faith on the other (Aechtner, 2020: 24–5). Audience numbers grew as Ham’s narrative seemed to resonate with American audiences in ways that Morris’s more academically couched presentations did not. After experiencing success, Ham received Morris’s blessing in 1994 to leave the Institute for Creation Research and form an American arm of the CSF, branded ‘Answers in Genesis’ (AiG). Though the Institute for Creation Research has remained an antievolutionist titan, Answers in Genesis would go on to become the most prominent young earth creationist organisation.

By their own account, AiG is the “world’s largest Christian apologetics organisation” that perhaps hosts the internet’s most significant religious websites (Ham, 2012b: n.p.; Kaden, 2019: 31). Answers in Genesis would go on to found a US$27 million, 70,000 square-foot Creation Museum in 2007, followed by the 2016 opening of Ark Encounter, a Noah’s Ark-inspired theme park located in Grant County, Kentucky. The museum drew crowds from across America despite being disparaged by experts. Within a year of opening, AiG reported that 404,000 people had visited the Creation Museum and less than three years later the museum welcomed its one-millionth guest (Ham, 2015: n.p.; “Millionth Guest Visits Creation Museum,” 2010: n.p.). The Ark Encounter theme park boasts a purported full-size replica of Noah’s Ark, built precisely according to biblical dimensions (AiG, 2023: n.p.).

In the years before Answers in Genesis became infamous for building Kentucky’s creationist attractions, however, Ham was pitted in a legal clash with his Australian partners in Brisbane. The dispute arose as a fight over the organisation’s leadership and its access to American audiences.

In 1997, Brisbane’s Creation Science Foundation had changed its name to Answers in Genesis-Australia, to clearly tie the Australian institute to Ham’s successful American brand. Ken Ham’s branch officially united with Answers in Genesis-Australia to form Answers in Genesis International (AiG-I), with ownership evenly divided between Ham in America and Wieland in Australia. Along with the Australian and American branches, AiG-I was also composed of several smaller Answers in Genesis groups located in the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth countries, including Canada, New Zealand and South Africa.

But in 2005, a leadership struggle erupted between Ham and the Australians back in Brisbane, when Wieland proposed a restructure of AiG-I’s board management. The suggested change called for each individual AiG division to have one vote at board meetings. This would have resulted in a decentralization of power, since much smaller international arms of the ministry, such as the New Zealand and South Africa contingents, would each gain the same voting share as Ham’s much larger American group (Bertelsman, 2009: 3). Ham interpreted Wieland’s suggestion as an attempt to seize control of his US operations because it was expected that the minor parties would follow Wieland’s voting preferences. This would give Wieland, by proxy, a majority stake on AiG-I’s board, even while the American body was eclipsing the Australian office in membership while maintaining 50 per cent ownership rights. Ham opposed Wieland’s proposal, and the relationship between the two creationists quickly fell apart. The disagreements intensifying to legal action over website content and copyright ownership. In the end, following months of disputations and a failed mediation attempt, both groups were split into two separate entities with litigation finally concluding in 2009.

During these proceedings, the Australian, Canadian, New Zealand, and South African branches were subsumed under the new designation of Creation Ministries International (CMI), which continues to be headquartered in Brisbane. The American and UK branches, on the other hand, remained under the auspices of Ham and AiG (“A New Name in the Creation Family,” 2006: n.p.; “Trouble in Paradise,” 2006: n.p.). Together with Mackay’s acrimonious departure from CSF, this would mark the second major schism to rend the Australian movement.

At the heart of the Ham-Wieland altercation was a struggle for control over Australian creationism’s American market share. Ham’s branch had grown rapidly to become the United States’ most influential creationist organisation, which maintained direct access to a substantial population of the world’s evangelical and fundamentalist Christians. While this was crucial for achieving AiG-I’s missiological goal of reaching the world with its creationist message, there were also vital commercial factors at play. Sales of antievolutionist products to American audiences, which included US subscriptions to the AiG-Australia owned magazine Creation, funnelled through the distribution axes of Ham’s Kentucky-based organization. Control of AiG in America, therefore, meant having command of the most significant component of AiG-International for outreach purposes, while also being able to sell creationist products to America’s antievolutionist consumers.

Court records reveal how such economic considerations, including magazine sales, steered CMI-AiG mediation efforts and sparked legal action (Bertelsman, 2009: 3-4, 14-16; “Trouble in Paradise,” 2006: n.p.) as internal fights over market access to the US tore Answers in Genesis-International’s union apart. As much as anything else, this lawsuit was demonstrative of Australia’s new status as a global exporter of creationism. Though Australian antievolutionists had imported American creationist materials in the twentieth century, they had now become leading suppliers of young earth resources to the United States, with control over this growing trade being a notable facet in courtroom hostilities. At the same time, the legal break did not hold back the operations of either AiG or CMI, as Australian creationists continued to expand their international enterprises.

All this prompts the question: why Queensland did became a creationist heartland in the first place, from which Australian antievolutionism, and leading antievolutionists, have been exported to the rest of the world? In offering an answer, we can consider the socio-political contexts of Queensland’s education policies under the premiership of Joh Bjelke-Petersen in the 1970s and 80s, along with the quirks of Australia’s non-governmental private school system. Together, these ingredients provided fertile ground for creationism to flourish in the Sunshine State.

Why Queensland?: Joh, Curricula, and Private Schools

A notable feature of Australian creationism is the role that Queensland educators played in advancing the movement. This is represented by the number of teachers who originally formed the Creation Science Foundation’s core membership. Along with Ham and Mackay, another high school science teacher, David Denner, was an initial member of the group. Additionally, John Rendle-Short, the University of Queensland’s Professor of Child Health, joined the CSF in its early days. The foundation also maintained an advisory board that was largely composed of educators, and by 1984, twelve of this board’s nineteen members were active school teachers (Harrison, 2004:191).

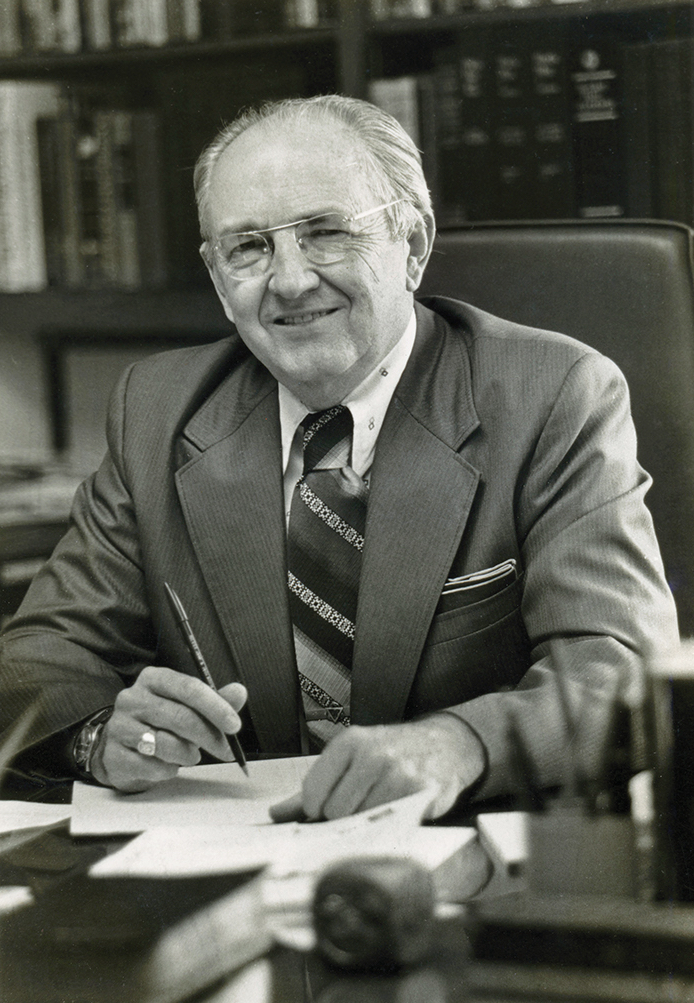

It is telling that throughout these years Joh Bjelke-Petersen led Queensland’s government. Bjelke-Petersen was a devout Lutheran and socially conservative. At his side was Lin Powell, the Queensland Minister of Education in 1982-87, who was in favour of giving creationist views equal time alongside evolutionary theory in high school science classrooms (Stevenson, 2012: n.p.). Consequently, the CSF’s early ranks were made up of numerous Christian antievolutionist teachers. These educators were under an education ministry that supported the teaching of creationism in Queensland schools, led by a premier who appealed to conservative religious voters in a relatively socially conservative part of the country. Collectively, these factors produced an environment in which teachers had the liberty to introduce young earth views to students in ways not necessarily sanctioned in other regions of the world.

Two further dynamics also had a bearing on creationism’s diffusion within Queensland’s educational system. The first included controversies over curricula adopted in Australia during the Bjelke-Petersen era, while the second involved the rapid growth of religious private schools. With regards to the first consideration, in the 1970s two new social studies curriculum packages became available to Australian schools. The first of these was the Man: A Course of Study (MACOS) lesson series, an American curriculum package developed in large part by the psychologist and educationalist Jerome Bruner. Bruner designed MACOS for primary schools to broaden students’ ideas about the very nature of humanity and societies using cross-cultural anthropological perspectives. The course incorporated films and discussions of social organisation, and subsequently won several awards in the United States. These included the American Educational Publishers Institute award, as well as an American Film Festival award, two CINE Golden Eagle awards, and an Emmy for its sophisticated use of film (“Man: A Course of Study: Welcome,” 2018).

Despite this praise, however, conservatives in the US opposed the curriculum. It was labelled as “an insidious attempt to take over the education and upbringing of our children,” which would lead young learners to question America’s cultural values, norms of morality, and its government (Conlan 1975, 389). In particular, critics maintained that MACOS was an anti-Christian, secular-humanist course that “propagated cultural relativism and evolutionary science as the only way to understand man, supposedly leading to amoral behaviour among the nation’s youth” (Fitchett & Russell, 2012: 475). This American controversy over MACOS began in 1971 and continued until the program was terminated in 1976. Like their American counterparts, Queensland’s religious conservatives reacted negatively to the curriculum package after MACOS was adopted in Australia. Many citizens voiced similar concerns to those raised across the US until the Bjelke-Petersen government finally banned its use in state schools in January 1978.

One month after MACOS was prohibited, the Queensland Cabinet also forbade the use of the ‘Social Education Materials Project’ (SEMP) curriculum. The SEMP was an Australian-produced social sciences teaching platform, developed in 1975 and similar to MACOS in its intent, which had been designed for secondary school students. Queensland’s vocal social conservative lobbyists, particularly morals and anti-pornography activist Rona Joyner, objected to these teaching resources because, as with MACOS, they were perceived to be secular humanist and pro-evolutionist in nature, while it also seemed to teach too liberally about family values, divorce, and blended households (Campbell, 2018: n.p.). Together, the banning of these curricula in Queensland reflected more than simply the religiously conservative, antievolutionist sentiments of many Queenslanders and their government representatives. Queensland’s MACOS/SEMP controversy also signalled an important shift away from state school-based education that was, to some extent, triggered by the public’s unhappiness with these two curriculum packages (Maddox, 2014: 93).

This would be the second dynamic that supplied a unique context by which creationism could prosper in Queensland. Beginning in the 1970s, Australia experienced an accelerated growth of small, independent Christian private schools throughout the country. Such schools would come to have an enduring effect upon the nation’s educational landscape, as parents found an alternative to secular state teaching programs such as MACOS and SEMP in Christian private school enclaves. In comparison to other OECD countries, Australia has some of the highest concentrations of non-governmental private schools, as well as significant rates of private school enrolment (Montt, 2011: 4). Additionally, more than 90 per cent of these private schools are affiliated with religious traditions, which far surpasses the proportion of private schools maintaining religious associations observed in most other nations (Buckingham, 2010: 27).

The story behind these educational idiosyncrasies can be traced to the release of Commonwealth funding to private schools in 1963. This took place under Liberal Prime Minister Robert Menzies, when Catholic colleges represented the most common variety of private school (Maddox, 2011: 301). Australia’s post-war baby boom had put a significant strain on both the Catholic and state systems, with the former nearing collapse as it struggled to meet monetary shortfalls while often teaching into poorer neighbourhoods. The federal government, therefore, elected to direct education subsidies to private schools in the hope of preventing the breakdown of Catholic education, which would have inundated the already overburdened public system with more students (Hanrahan, 2018: n.p.).

Over time, this model provided the means for new religiously-affiliated private schools to be established across the country, as non-Catholic private schools were now able to launch using this same source of educational funding. These schools provided instruction that satisfied the compulsory state and federal education requirements but could do so within a particular religious framework. From the 1970s onward, this framework was increasingly Protestant in nature, with the majority of new private schools bearing evangelical and/or fundamentalist Christian affinities (Maddox, 2011: 301–302). Many parents in Queensland and other Australian states turned to these types of Christian school as they sought to protect their children during and after the MACOS and SEMP controversies. Such schools marketed the teaching of ‘Christian values’, and often instructed students about creationism alongside evolutionary theory, as had previously been espoused by Lin Powell.

The teaching of religiously motivated creationism in both public and state schools continues to make headlines into the 21st century (“Creationism in Schools,” 2013: n.p.) News agencies, for instance, highlighted a 2011 invited lecture given by John Mackay at Gympie State High School, as well as reports of creationism being taught in optional religious instruction classes and science courses (Mitchell, 2013: n.p.; Sarah, 2011, n.p.).

From Queensland to the World

In this way, the legacy of the Creation Science Foundation can be traced back to an original stakeholder base made up of numerous Queensland educators. These educators worked under the Bjelke-Petersen government, which was itself opposed to the ‘secular’ and evolutionist curricula of MACOS and SEMP, while being supportive of teaching creationism in schools. Such contexts provided optimal socio-political conditions for creationism to mobilise in the state, further aided by the growth of state-funded, religiously affiliated private schools. This expansion was fuelled by Commonwealth subsidies, resulting in Australia’s relatively high concentration of religious non-governmental colleges. Many of these private schools have been Christian and have been open to teaching creationism.

Ultimately, the CSF was able to thrive in these circumstances, and export an Australian style of young earth creationism abroad. One result was that Answers in Genesis, the world’s largest and most profitable antievolutionist organisation, was founded as an Australian creationist mission originating in Brisbane. From there, creationism with an Australian accent spread from Queensland across the globe.

Sources and further reading

Aechtner, T. 2020. Media and the Science-Religion Conflict: Mass Persuasion in the Evolution Wars. Abingdon: Routledge.

Aechtner, T. 2021. ‘Creationism with an Australian Accent: Politics, Schools, and Global Exportation.’ Almagest 12: 124–48.

‘About The Ark.’ .AiG, accessed 2023. https://arkencounter.com/about/

Bertelsman, W. O. 2009. ‘Answers in Genesis of Kentucky v. Creation Ministries Int’l, Ltd.’ United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit. Lexington, Kentucky.

Buckingham, J. 2010. The Rise of Religious Schools in Australia. Sydney: Centre of Independent Studies.

Campbell, C. 2018. ‘MACOS and SEMP: Queensland (and Australia), 1970s-1990s,’ Dictionary of Educational History in Australia and New Zealand, accessed 2018. http://dehanz.net.au/entries/macos-and-semp/

Conlan, J. B. 1975. ‘M.A.C.O.S.: The Push for a Uniform National Curriculum.’ Social Education 39, 6: 389–96.

‘Creationism in Schools.’ 2013. ABC Q&A, accessed 2013. https://www.abc.net.au/qanda/creationism-in-schools/10659880

Fitchett, P. and W. B. Russell. 2012. ‘Reflecting on MACOS: why it failed and what we can learn from its demise.’ Paedagogica Historica 48, 3: 469–84.

Ham, K. ‘Creation Down Under.’ Answers in Genesis, accessed 2012a. https://answersingenesis.org/blogs/ken-ham/2012/09/07/creation-down-under/

Ham, K. ‘The History of AiG through July 2012.’ Answers in Genesis, accessed 2012b. http://www.answersingenesis.org/about/history

Ham, K. ‘Propaganda War Against the Ark!’ Answers in Genesis, accessed 2015. https://answersingenesis.org/ministry-news/ark-encounter/propaganda-war-against-the-ark/

Hanrahan, C. 2017. ‘Here’s how Australia’s schools are funded — and we promise not to mention Gonski.’ ABC News, accessed 2018. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-05-30/school-funding-explained-without-mentioning-gonski/8555276

Harrison, J. 2004. Joh Bjelke-Petersen: Pietism and the Political Culture of Queensland. Brisbane: University of Queensland Press.

Kaden, T. 2019. Creationism and Anti-Creationism in the United States: A Sociology of Conflict. Cham: Springer.

Maddox, M. 2011. ‘The Church, the State and the Classroom: Questions Posed by an Overlooked Sector in Australia’s Education Market.’ The University of New South Wales Law Journal 34,1: 300–15.

Maddox, M. 2014. Taking God to School: The End of Australia’s Egalitarian Education? Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin.

‘Man: A Course Of Study (MACOS): Welcome.’ University College London, accessed 2018. https://libguides.ioe.ac.uk/macos

‘Millionth Guest Visits Creation Museum.’ Answers in Genesis, accessed 2010. https://answersingenesis.org/ministry-news/creation-museum/millionth-guest-visits-creation-museum/

Mitchell, N. ‘Creationism in Queensland schools.’ ABC News, accessed 2013. https://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/lifematters/creationism-in-queensland-schools/4496260

Montt, G. 2011. Private schools: Who benefits? (Vol. 7). Paris: OECD Publishing.

‘A New Name in the Creation Family.’ Answers in Genesis. https://answersingenesis.org/ministry-news/ministry/a-new-name-in-the-creation-family/

Numbers, R. L. 2002. ‘Creationists and their critics in Australia: an autonomous culture or “the USA with Kangaroos”?’ Historical Records of Australian Science 14, 1:1–12.

Roberts, M. 2008. Evangelicals and Science. Westport: Greenwood.

Sarah, E. ‘Row over creationist’s class lecture, p. 2.’ The Australian, accessed 2011. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=anh&AN=20110815N002264924&site=ehost-live

Stevenson, C. ‘Faith in schools: The dismantling of Australia’s secular public education system.’ ABC News, accessed 2012. https://www.abc.net.au/religion/faith-in-schools-the-dismantling-of-australias-secular-public-ed/10100234

Trollinger, S. L. and W. V. Trollinger, Jr. 2016. Righting America at the Creation Museum. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

‘Trouble in Paradise: Answers in Genesis Splinters.’ National Center for Science Education, accessed 2006. https://ncse.com/library-resource/trouble-paradise

Related articles