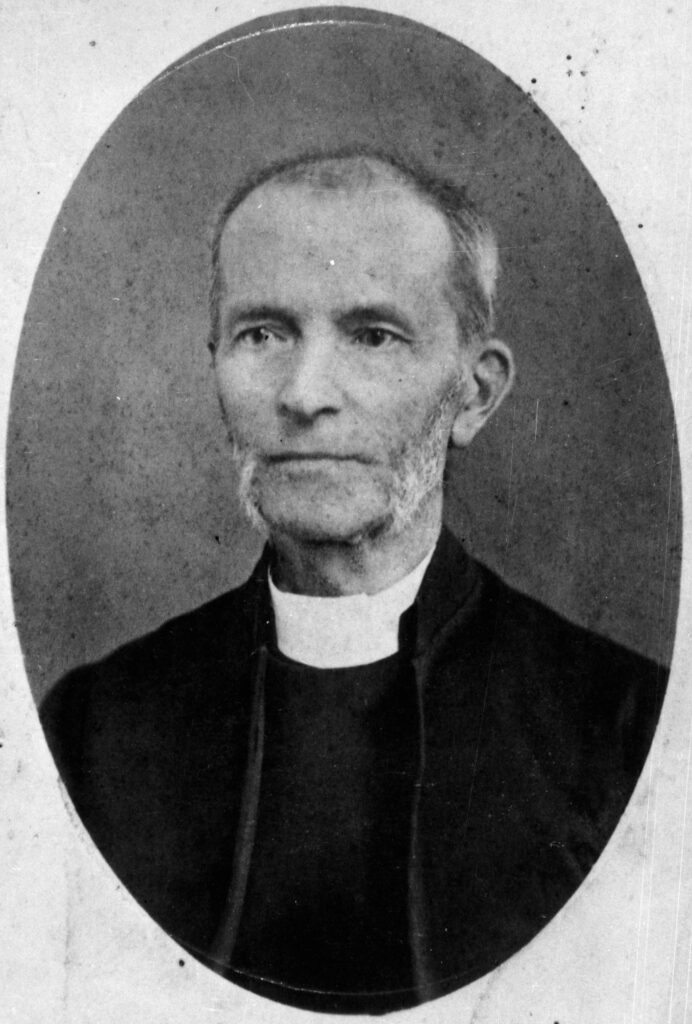

Benjamin Glennie, Apostle of the Downs

The diary of Anglican priest Benjamin Glennie details the challenges and privations of religious ministry on Queensland's colonial frontier.

By Robert Hogg

This is a 15 minute read, published June 2024.

A transcribed diary held at the State Library of Queensland is a precious memento of religious life on the Darling Downs in the first decades of colonial occupation. It records the work and travails of Benjamin Glennie, an Anglican clergyman later remembered as ‘The Apostle of the Downs.’ In December 1854, after noting church attendances at Drayton for the month, Glennie recorded 26 attendees at his Christmas Day service, but only four of these received Holy Communion, “namely Mesdames Moffatt, Lord and Glissan and Miss North”. Other challenges had presented that month:

(10) [i.e. December 10] Afternoon violent hail storm which did much damage and beat through the shingles, preceded by high wind which drove dust into all parts of the house. Cold evening had to my dress [sic]. (11) Quiet cold night. Double blankets. (16) Very appressive [sic] night could not sleep without opening windows, mosquitoes very bad. (17) Suffocating morning and a frightful day. Hot night. High wind quite knocked up. Headache, Cooler at night. (23) Wind east. Rain all day. Quite cold had a fire. (25) Most melancholy Xmas Day. Four women at Holy Communion while there was great feasting in all directions.

This entry characterises much of Glennie’s ministry on the Darling Downs in the 1850s. He experienced indifference to religious observance on the part of most parishioners, poor school attendance, an unpredictable and often fierce physical environment, and poor personal health. He also undertook an extraordinary amount of travel on horseback, in this instance recording 2,344 miles for the year 1854. It also demonstrates an eye for posterity, as Glennie returned to his diary to make significant amendments after the original entries.

While not the first Anglican minister in what later became Queensland, Glennie can nevertheless be regarded as a pioneer clergyman, particularly for his work establishing Anglicanism on the Darling Downs. His diary illustrates the particular difficulties churchmen faced on the colonial frontier. In Glennie’s case, these included arduous travel over vast distances, extremes of heat and cold, attacks from fleas, mosquitoes, and flies, as well as recurring and debilitating illness.

Glennie’s view of the frontier was inevitably coloured by ideas and assumptions based on his personal history and experiences. No one could entirely release the cultural beliefs they took to the frontier, and these beliefs must have influenced how his experiences were perceived and recorded. In Glennie’s case these were formed by education at his father’s private school in Dulwich, King’s College London, and later Christ’s College Cambridge, where he received his BA in 1847. Prior to emigrating to Australia he worked as a private tutor on the Continent and was apparently fluent in French, German, Spanish, and Italian.

No doubt Glennie possessed many of the attitudes prevalent among the English clergy of the Established Church in the nineteenth century. By virtue of his university education he would have been regarded as a gentleman, and probably had a gentleman’s tastes and manners. He likely believed that one of the duties of a clergyman was to guard and sustain the existing social hierarchy as the one most likely to guarantee social harmony and unity. Following three of his brothers (Henry, a landowner, James, a doctor and Alfred, a farmer), Glennie arrived in Australia in January 1848 aged thirty-six with the first Bishop of Newcastle, Dr William Tyrrell. He was made a deacon by Tyrrell in March 1848 and sent to Moreton Bay, then a remote settlement in the northerly part of New South Wales. When Glennie arrived in Moreton Bay in 1849, he was entering a region that had been almost totally bereft of any formal religious institutions and the dominion of the church was insignificant. He was preceded by the Rev. John Vincent in 1829 and Rev. John Gregor in 1843, but neither had made much impression.

Religion on the Queensland frontier

The first census of the Moreton Bay district had been undertaken in 1846. It showed the non-Indigenous population of what is now the area of modern Brisbane to be some 2,525 people. Of these, 50.2 per cent described themselves as Church of England, 27.9 per cent as Roman Catholic, 16.2 per cent as Presbyterian, and 1.1 per cent as Wesleyan, with 4.6 per cent described as being of some other religious denomination. Yet the defining feature of religious observance at this time was its absence. While Anglicans were numerically dominant, this did not necessarily equate to church attendance, a fact to which Glennie’s diary frequently alludes. Congregations on the Downs were usually small, numbering no more than a handful of people. In Brisbane, with approximately 1,250 Anglicans, the average congregation was only 100, with as few as eight communicants. For most settlers, with the exception of the Irish, religion was an object of gross indifference. When Glennie’s predecessor John Gregor toured outside of Brisbane little interest was shown in his services. On one occasion at Archer’s station, he preached to the lone Irish Protestant.

This apparent lack of interest in religion is at least partly explained by the class structure of English society, transplanted as it was to the Australian colonies. In England, the connection of the Church of England to the aristocracy and landed gentry was strong. The middle classes also displayed a firm adherence to religious practice, particularly the evangelical variety. However, among the emergent working classes the church was held in disdain. The majority of immigrants to Queensland came from the labouring class and brought their disdain for the Church with them. The identification of the Church with the ruling class meant indifference, at best, was the dominant feeling towards it. Sometimes this grew into positive resentment.

In Brisbane Glennie rapidly set about restoring church life. He had initial success increasing the congregation at the temporary St John’s church. Within weeks of arriving in Brisbane he had re-started the Sunday School which had lapsed. He prepared candidates for confirmation and, by the time Bishop Tyrrell visited in June 1848, was able to present eight candidates for the confirmation service. He restored evening prayer at St John’s, which had been discontinued under Gregor’s tenure. Tyrrell’s visit in June also gave impetus to the building of a new church, school and parsonage, and Glennie was actively involved. Under Tyrrell’s direction, Glennie laid the foundations for the division of southern Queensland into the smaller parishes of Brisbane, Ipswich, and the Darling Downs. Glennie also became chaplain of Brisbane jail, and was interested in the establishment of a public hospital. He visited the nearby township of Ipswich each month, and made a lengthy tour of the Darling Downs during August 1848.

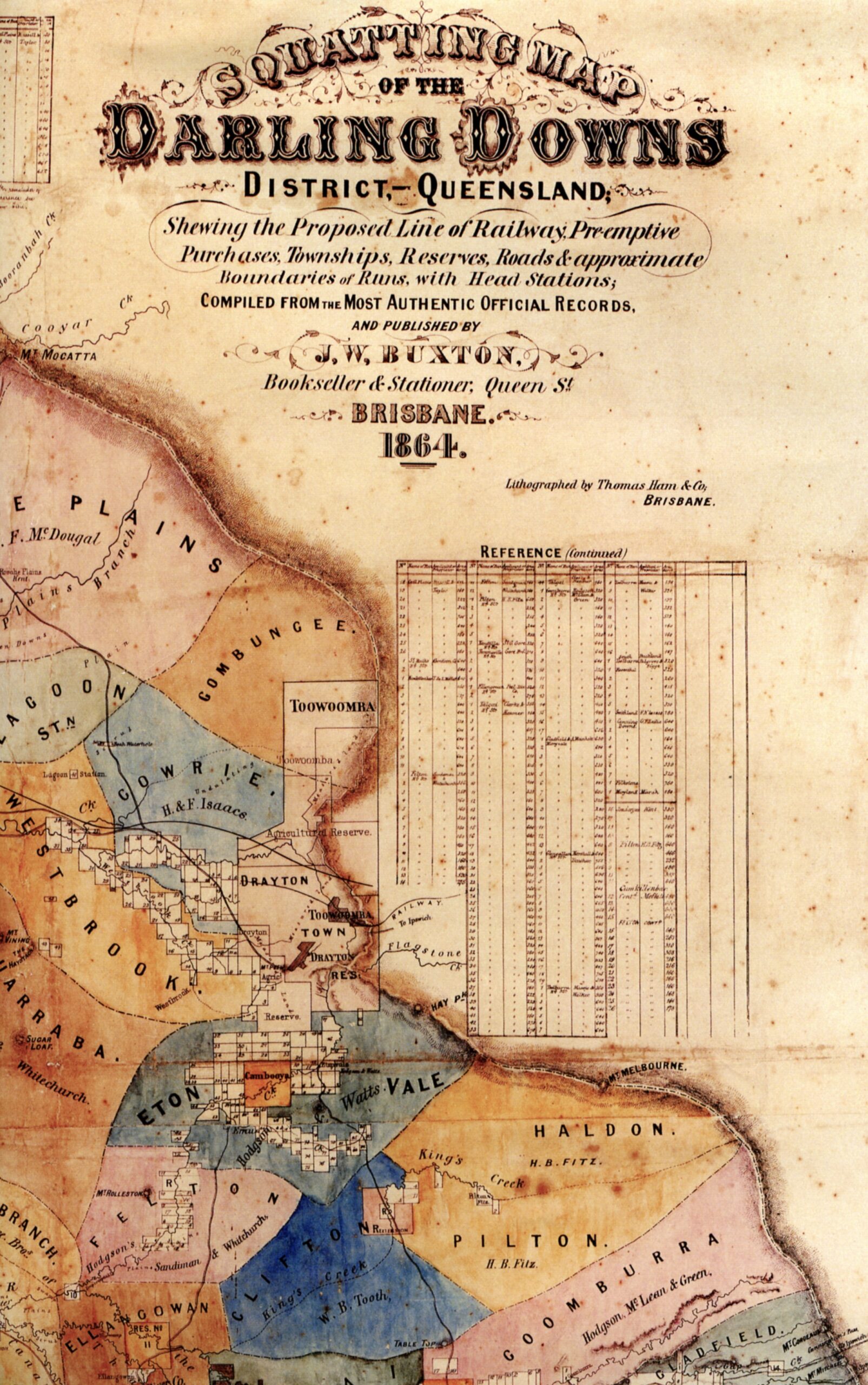

The Darling Downs frontier had opened some twenty years earlier, when the Scottish botanist and explorer Allan Cunningham trespassed on the lands of the Kambuwal, Keiyan, and Kilabal people to camp on the banks of the Condamine River in early June 1827. Subsequent pastoral occupation and settlement was spearheaded by Patrick Leslie and his brothers George and Walter. In 1840 they claimed an enormous area of land comprising all the headwaters of the Condamine, which they named Canning Downs. However, it became apparent that this run was too large and they moved their head station to what remained the Canning Downs portion of the run with the remainder becoming the Toolburra run.

The Leslie brothers’ incursion into indigenous lands opened the flood gates for others to follow. Arthur Hodgson and Gilbert Eliot claimed a run they named Eton Vale, north of where the Leslies settled and south of the present-day Toowoomba. In 1841 the Gammie brothers (like the Leslies from Aberdeen, Scotland), walked to the Downs with their sheep from the Liverpool Plains and claimed what became known as Talgai. Throughout 1841 Tummaville and Yandilla were established, followed by Gladfield and Clifton. On the northern Downs squatters claimed Jimbour, Myall Creek, and Jondaryan. The largest claim was Jimbour, which extended from the Bunya Mountains in the east to the Condamine in the southwest, from Jandowae in the north to Dalby in the south — 300,000 acres in all. By late 1841 the invasion of the Downs was complete.

Ordained a priest in 1849, Glennie was appointed to Drayton, at that time the principal town of this new pastoral region, with responsibilities across the Darling Downs. Taking up a permanent ministry at Drayton in 1851, Glennie led his parishioners in prayer and worship, preached the gospel, celebrated the sacraments, consoled the sick, visited homes, advising and admonishing individuals as he saw the necessity. It was the beginning of an arduous appointment, as he served the district for over twenty-five years including in Warwick from 1860 to 1872 and again in Drayton from 1872 to 1876. Between January 1848 and September 1860 Glennie kept a diary of his efforts. He recorded the places he visited and the people he saw, the numbers attending his services, and the baptisms, funerals, and weddings he performed.

The predominant feature of Glennie’s efforts to sustain and expand Anglicanism on the Darling Downs was the constant and arduous travel. His diary records the distance he travelled every month. In January 1852, in the heat of summer, he rode 238 miles on horseback. In February the same year he rode 256 miles, and in March another 425 miles. With an area of 90,000 square kilometres, vast and imposing, the distances and heat of the Darling Downs challenged the pleasant image of small English country parishes conjured up by novelists like Anthony Trollope, and replicated in the Australian landscapes of Conrad Martens.

Ailments and endurance

Glennie certainly found it difficult to cope with the physical challenges itinerancy entailed. Even during the early stages of a trip to the Downs he found the going difficult. His diary records: “Rode to Woogaroo, much fatigued. Thermometer 98. Lying on the sofa I imagined the sun was burning through the shingles. In the afternoon to Ipswich. Heat, mosquitoes and noise … rendered sleeping very difficult.” What makes Glennie’s endurance all the more remarkable is that he did not enjoy robust health, even at the best of times. Early in his diary in 1848 there are a number of entries in which he notes he had “headache.” On Sunday 7 October 1849 in Brisbane, he recorded “Hysterics at Kangaroo Point.” On Sunday 26 May 1850 he “broke down” twice: once during a service in Warwick and then again during the evening service at Goomburra. Scattered throughout the rest of the diary are references to influenza, being “unwell and weak,” and being “very nervous and shaky.” In 1859 he wrote to the bishop “giving unsatisfactory account of the state of my health. Wished to remain until the Bishop of Brisbane arrives and then go home.”

So what exactly did ail Glennie? Anyone can catch the ’flu, and Glennie was probably no exception. But references to “hysterics,” “breaking down,” feeling “shaky and nervous,” and the “old complaint,” over the twelve years covered by the diary, suggest something chronic, and perhaps not physical in origin but nevertheless physically draining. Only once does Glennie record consulting a doctor — Brisbane’s Dr David Ballow — who recommended he rest for a month. Glennie did so at Canning Downs station. He obviously confided in his bishop, but it seems Bishop Tyrrell did not consider Glennie’s illnesses debilitating to the extent that he should have been relieved of his duties.

Diagnosis at a distance of 170 years is a fraught business, but to the modern reader of Glennie’s diary it may appear that he was suffering from depression, or “melancholia” as it would have been called at the time. There are differences and similarities between today’s depression and the melancholic states of past eras. Nevertheless, Glennie seems to have displayed symptoms analogous to those presently thought to be indicative of depression: anxiety, apprehension, a despairing state of mind, and lack of energy. It also appears that Glennie’s ailment had no apparent cause, a feature of both illnesses.

How did his illness affect his work? While Glennie’s illness predates his time on the Downs, the exigencies of a frontier incumbency could not have helped. Ordinary clerics in nineteenth-century England faced a number of pressures and stress in their lives. Added to these, the physical isolation and stresses of the frontier would have been difficult, perhaps exacerbated by the social distance from many adherents that Glennie may have felt, and relieved only by the periodic company of his social equals. It seems that Glennie’s illness was episodic and prevented him from fulfilling his duties from time to time. It seems his periods of disability continued for weeks at a time. Obviously, in the instance of the “hysterics” at Kangaroo Point and the “breakdowns” of May 1850, he could not fulfil his clerical duties. But Glennie battled on, not allowing his disability to derail his efforts. That fact that he did so is testament to his devotion, courage and perseverance.

Attendance and observance on the Downs

Glennie’s congregations were always small, often in single figures, and he was often dismayed by the low numbers of Anglicans taking Holy Communion. On his first visit to the Downs in 1848 he visited Cecil Plains station but, sadly, “no congregation could be got.” There were several reasons for small congregations. The population of the Downs was dispersed over a very wide area, and in some locations numbers were naturally small. In one instance an outbreak of typhus in Warwick kept the people of Canning Downs station away. The distances, heat and occasional floods that hindered Glennie would also have deterred many. Numbers were also not helped by a predilection for drinking and entertainment on the part of parishioners. On Christmas Day 1852, for example, Glennie complained that there was no one in church but Henry Wiseman, a Drayton landowner. A large and festive dinner party at Eton Vale station was the preferred method of celebration for most.

Glennie’s diary provides insights into the patterns of Anglican attendance and observance on the Downs at this time. An entry for December 1857, for example, indicates that, apart from the large local Aboriginal population, there were 612 people living at Toowoomba and a further 250 at Drayton. But on 6 December 1857 only thirty-one attended the service at Drayton and eighteen at Toowoomba. Christmas Day 1857 saw only twenty-eight Toowoomba Anglicans in church. However, the evident importance attached by settlers to church weddings, baptisms, and funerals demonstrates a greater religiosity than church attendance indicates.

In addition, preaching to those who did attend services did not necessarily occur in a formal church setting. On his first visit to the Downs in 1848, Glennie conducted a service at Horton’s Bull’s Head Inn at Drayton. Morning prayers were often conducted in the courthouse at Drayton, and he seems to have once conducted a service in the unpromising environment of Ayerst’s boiling down works, where the carcasses of sheep were boiled down for their fat. On several occasions Glennie remarked anxiously in his diary on the unsatisfactory nature of these places: “Kirby’s Public House in too drunken a state to hold a service. Adjourned to Young’s.”

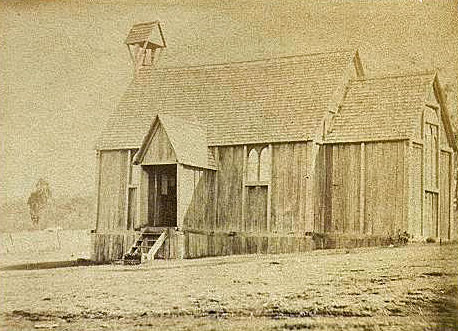

Given these challenges, the establishment of formal church buildings was an early priority. As soon as practicable Glennie took steps to create more suitable spaces for religious observance. At his Drayton parsonage in November 1852 he converted two rooms by removing some slab partitions and putting a communion table at the east end and placing a prayer desk at the north end. Glennie saw the establishment of churches and schools in his new territory as an important part of his role, and as one of the essential tasks of a frontier ministry. The parsonage was built in stages between September 1850 and August 1852 on land Glennie had acquired at Drayton. It would probably have been completed sooner if the builder Glegg and his men been able to maintain sobriety.

However, the erection of churches would take longer. In February 1853 Glennie sought permission from the bishop to collect funds for building churches at Drayton, Dalby, Warwick, and Toowoomba. He begged for the funds on his circuit around the parish. However, parishioners could be reluctant. In 1856 more land was acquired in Drayton, but the first service was not held in the new slab-timbered, shingle-roofed St Matthew’s until 23 January 1859.

The Darling Downs Gazette described the building in functional terms as having a nave, turret, chancel, and porch, but noted the lack of stained-glass windows. The Moreton Bay Courier, in contrast, was sharp in its criticism and thought the building was a “disgrace” due to the miserliness of Downs Anglicans who enjoyed comfortable homes but were content to have a common slab building for a church.

Glennie’s constant travel and preaching, his engagement with the Darling Downs elite, his performance of the sacraments, his fundraising, property acquisition, and building, were all part of a concerted and intensive effort to overcome the tendency he perceived as Anglican apathy on the frontier. On the face of it, the low rate of church attendance suggests that the Downs populace was not particularly religious, and Glennie needed considerable perseverance and strength in order to construct a religious presence.

After his arduous work establishing the foundations of Anglicanism on the Darling Downs, Glennie served the parish of Toowong in Brisbane before retiring to Wynnum. In 1868 he married Mary Brougham. They had no children. Glennie retired from active work in 1888 and died in 1900.

Sources and further reading

Benjamin Glennie Diary 1848-1860 [transcription], State Library of Queensland, OM67-25 and Fryer Library, University of Queensland, F1564 (copy).

French, M., Conflict on the Condamine: Aborigines and the European Invasion (Toowoomba: Darling Downs Institute Press, 1989).

French, M., Pubs, Ploughs and Peculiar People: Towns, Farms and Social Life (Toowoomba: USQ Press, 1992).

Heeney, B., A Different Kind of Gentleman: Parish Clergy as Professional Men in Early and Mid Victorian England (Hamden CT: Archon Books, 1976).

Le Couteur, H., “Brisbane Anglicans 1842–1875” (PhD diss., Macquarie University, 2007).

Rayner, K., “A History of the Church of England in Queensland” (PhD diss., University of Queensland, 1962).

Rayner, K., ‘Glennie, Benjamin (1812-1900)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography Vol. 4 (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1972). Online (2006): https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/glennie-benjamin-3621

Related articles