Lay Preachers in Methodism and the Uniting Church: Alan and Dorothy Demack

Decades of service as lay preachers in the Methodist and then Uniting Church traditions has endowed this Rockhampton couple with a deeply enriching experience of community life. Many religious traditions have a special role for ‘laypersons’, but these roles are often changing.

By Annabel Demack

This is a 15 minute read and 25 minute video, published June 2024.

The Uniting Church of Australia formed in 1977 through the union of three separate denominations: Congregationalists, Presbyterians and Methodists. Lay (or ‘local’) preaching by un-ordained members of a congregation had long been a characteristic feature of Methodism, but Congregationalists had historically rejected the centralised administration that would allow it. Meanwhile, Presbyterians prioritised the formal education of their ministers extremely highly (Barnes, 1997: 12; Prentis, 2008: 230).

At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, Alan and Dorothy Demack (by then retired and living in Rockhampton) had over six decades of experience as lay preachers. In Dorothy’s case this was supplanted by formal ordination as a pastor in the Uniting Church in 1987. Their story illustrates how lay preaching featured in the Methodist and later Uniting Church traditions in Australia and how, for a range of reasons, its future appears uncertain.

Local preachers in the Methodist tradition

As Methodism developed in England in the late eighteenth century, its founder John Wesley had quickly seen the value in lay preachers, not only for the wisdom they brought as common people, but also within his itinerant vision that ministers should travel from place to place on rotation. Lay preachers could remain in their communities and lead sermons in the absence of the travelling Methodist minister (Brown, 2019: 82–85).

This allowed Methodist communities to sustain themselves. This tradition easily transplanted itself to Australia, and particularly to the goldfields with large working-class populations. One lay preacher, usually of the same background as the miners, would begin preaching and a community formed around him, growing until they built their own church and finally requested a minister from England. Only lay preachers could have succeeded here, as they were part of the community fabric, not trying to impose an erudite institutional worldview (Brown, 2019: 93–4).

However, as frontiers expanded, Methodism found a home in the new Australian cities and their outskirts, often sharing community halls with several other denominations. This coincided with an increased formalisation as the Methodist Church grew in confidence and began establishing educational institutes of their own. By the 1950s many young university men were complementing their studies with lay preacher training in order to better serve their communities (Alan and Dorothy Demack, 2021).

When the three denominations worked towards unity in the 1960s and 1970s, the distinctive ministry of lay preachers was preserved despite some hesitation. According to the ‘Basis of Union’ (Uniting Church in Australia, 1992: 13):

[The church] will seek to recognise those endowed with the gift of the Spirit for this task, will provide for their training, and will gladly wait upon that fuller understanding of the obedience of Christians which should flow from their ministry. Such members will be called Lay Preachers.

One commentary explains why this was preserved despite being uniquely Methodist: “the response of faith, love and hope must sometimes be articulated by those who live the common life, whose trade or profession takes them into parts of the world closed to the experience of the minister” (McCaughey, 1980: 81).

Indeed, one of the first orders of business at the first Queensland Synod in 1977 was to formalise lay preacher training, establishing Alcorn College as a training facility, as well as a correspondence course. This occurred despite concerns over a lack of motivation for encouraging lay training from the clergy, and logistics of one educational centre, “education for lay ministries, it was hoped, would recognise, encourage, facilitate and use the gifts of all members in service.” (Richardson, 1997: 185) This became Trinity College in 1989, and has since remained the main provider of training in Queensland.

Introducing the Demacks

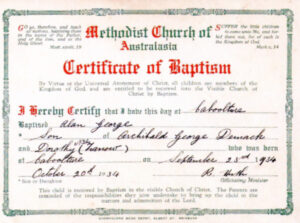

Alan, a former Justice of Queensland’s Supreme Court, was born in 1934 in Caboolture. He was raised in a German Methodist family, who sent him to Brisbane Boys’ College, a school operated by the Presbyterian and Methodist Schools Association, and later to the University of Queensland to study law.

Rev. Alan Walker’s ‘Mission to the Nation’ in 1954, meanwhile, inspired Alan to become a lay preacher, and encouraged by his local minister he completed his study by 1957. He felt no particular call, and was instead motivated by the opportunity to serve. In his own words, as a young man he decided to

… look at my capacities and to work out how I should commit myself to church and community, because they belong together in the work of J.H. Oldham, who wrote Life is Commitment and I decided that I would commit myself to the service of the church with preaching and the service to the community through the practice of law.

Born in 1936 in Melbourne, Dorothy was raised as a Methodist, attending the Methodist Ladies’ College, and becoming part of the Student Christian Movement (SCM) while studying to become a French and English teacher. At a SCM conference, she met Alan and the two married in 1959.

Figure 2: Dorothy Alexander and Alan Demack, Student Christian Movement conference, c. 1955 (Demack family).

Life and work in Jindalee and Rockhampton

They started their family at Bardon, where Alan regularly took services at the Kennedy Terrace and Bardon Methodist churches. In 1972 the family moved to Jindalee, in the fast-growing Centenary suburbs of western Brisbane, and joined the Jindalee Co-Operative Church. This is also where Dorothy led her first sermon. Though she would not become a lay preacher for some years, she rose to the occasion by filling in when Alan was unable to deliver a sermon on his scheduled week.

The Jindalee Co-Operative Church began as one of the earliest churches in Brisbane, erected by the pioneer Sinammon family. The Methodist church joined forces with the Congregationalist and Presbyterian when it moved to a bigger location in 1969, in this foreshadowing the later creation of the Uniting Church of Australia. In 1992, the church upsized again to a site on Burrendah Road.

The church has long been a central part of the Centenary Suburbs community. Since the area was established as a property development, residents were eager to establish their own community identity, and did so based on the Jindaleader, a community newsletter. Early editions featured the names and addresses of new arrivals, while later papers focussed on community groups, tidy streets, and local interest highlights such as a pet photography competition. The church was regularly advertised in these pages.

Local worshipper and historian, Geoff Hunt, offered these reflections. Another community member, Jane Dale, remembers Alan and Dorothy as “wonderful servants of the church.” They both served on the Sunday School board for a number of years, with Dorothy both teacher and superintendent of primary, and Alan briefly superintendent. Alan also served on the Property Board.

In 1977 the Demack family moved to Rockhampton, where Alan had been appointed as Supreme Court Justice, and this is where Dorothy’s service would start. As she remembers:

There’d be a Sunday when all the ministers, all six of them, had gone off to presbytery and we had at least four places where there needed to be somewhere leading worship … You know the ministers really struggled to find people to lead worship and that’s the point at which I thought ‘I could perhaps offer myself, I think that’s something that I would be able to do if I was properly trained,’ so I offered myself to be trained as a lay preacher.

Lay preaching and local ministry

Dorothy completed her training in the early 80s and served in Rockhampton for a time, until she decided to make a change. In 1987 she was commissioned as a lay pastor due to changes in their local area.

We needed, I think one or two of our ministers had moved on to somewhere else and we were in need of ministerial placements. And really we thought, with the number of minsters we’ve actually got and the need throughout the Uniting Church of ministers in placement, we’re a bit unlikely to be given an ordained minister, and that’s when Alan got his good idea. He said to me ‘well you’re a lay preacher, you could be a lay pastor and you could be the pastor for the part of our parish which is on the south side of the river.

She quickly discovered the differences when she was asked to attend to the bedside of a dying man. As she later reflected:

That was learning how to be a pastor as distinct from a preacher, ’cause when you’re a pastor you’ve got to look after your people in all their various problems and crises, as well as leading worship.

![Dorothy_Praise you o god Figure 4: Dorothy Demack, ordained Uniting Church minister [location and date needed] (Demack family).](https://qareligion.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Dorothy_Praise-you-o-god-1024x724.jpg)

Figure 4: Dorothy Demack, ordained Uniting Church minister [location and date needed] (Demack family).

From the 1990s, and especially after Alan retired from the bench, the couple have served various congregations around the Rockhampton region, notably at Bushley and Mount Morgan:

… we were happy to get up early on Sunday morning and be out at Bushley, which is a half hour drive, and be there by 8 am, lead worship there, then drive another half hour up to Mount Morgan, lead worship at 10 o’clock, we were perfectly happy to do that, but it’s no longer required [due to Covid-19 restrictions]. So now, South Rockhampton and Mount Morgan now both worship at 9am, which does mean that every Sunday our parish has to find an extra person, not just the minister. The minister goes to Mount Morgan once a month to lead the communion service, in which case someone else has to lead South Rockhampton, but it does mean that every Sunday really, two people are needed …

The COVID-19 pandemic ended this career of busy service, and Alan and Dorothy have now moved on to a quieter retirement in Rockhampton.

The future of lay preaching

The outlook for lay preaching in the Uniting Church is uncertain. The Rev. Heather Den Houting, formerly Queensland General Secretary of the Uniting Church, notes that “the church adapts its ministry needs as community and social expectations change. Television, online resources and live streaming have all mitigated the need for a lay preacher who only brings a sermon. Instead the demand for Lay Pastors, those who minister to communities, and Chaplains, those who minister in communities has skyrocketed” (pers. comm. 2021).

She ascribes part of this change to a shift in community needs. A few decades ago, lay preachers filled gaps between ministers, to make sure the congregation didn’t miss their Christian education for the week. Now, as Sunday sermons are no longer regarded as authoritative and essential, the need for such a system has faded. Instead, congregations want a church leader who will focus on their community needs, not simply provide a sermon. The irony here is that the earliest lay preachers did precisely this, as do current rural preachers who remain a deeply ingrained part of the community.

The Rev. Nigel Rogers, Dean of Formation at Trinity College, has a different perspective, however. He is concerned that the move away from lay preachers is an indicator of intergenerational differences, and sees it in overall terms as a detriment to the life of the church. This is because of their community importance: if a community can’t afford an ordained minister, lay preachers may be the only way to keep the church going, something of particular importance in rural areas where church is a centre of daily life. He sees the path forward as a return to missional focus (Rogers, 2021).

In Alan and Dorothy’s life story and experiences, we see the recent history of this enduring institution as it has played out in the Queensland context.

Oral history interview: Alan and Dorothy Demack

Sources and further reading

Barnes, G. 1977. ‘“Forbearance and Mutual Indulgence Unto Saints of all Persuasions”: Congregationalism’s Contribution.’ In W. W. Emilsen and S. Emilsen (eds), Twenty Years: The Uniting Church in Australia 1977–1997. Parramatta: United Theological College Publications, 35–46.

Brown, B. T. 2019. ‘The Ministry of Lay Preacher.’ In Second Uniting Church National History Conference. Melbourne.

Demack, A. and D. 2021 and 2022. Interviewed by Annabel Demack, Brisbane (22 August 2021), and Geoff Ginn, Rockhampton (1 November 2022).

Den Houting, H. October 2021. Interview conducted by Annabel Demack, Brisbane.

Harrison, D. and J. Harrison. 2003. ‘Queensland.’ In Emilsen, W.W. and S. Emilsen (eds), Uniting Church in Australia: The First 25 Years. Melbourne: Melbourne Publishing Group, 98–129.

McCaughey, J. D. 1980. Commentary on the Basis of Union. Melbourne: Uniting Church Press.

O’Farrell, P. 1989. ‘Spurious Divorce? Religion and Australian Culture.’ The Journal of Religious History 15, 4: 519–24.

Prentis, M. D. 2008. ‘The Presbyterian Church of Australia 1901-1977: An Overview.’ Church Heritage 15, 4: 227–43.

Prentis, M.D. 2010. ‘Religion in Australian History.’ Church Heritage 16, 3: 186–204.

Richardson, I. 1997. ‘The Changing Face of Lay Education 1977–1997.’ In Emilsen, W.W. and S. Emilsen (eds), Twenty Years: The Uniting Church Australia 1977–1997. Parramatta: United Theological College Publications, 182–91.

Rogers, N. August and November 2021. Interviewed by Annabel Demack, Brisbane.

Sims, N. 1995. ‘Ministerial Leadership from a Parish Perspective Within the Uniting Church in Australia’ unpublished PhD thesis, School of Theology, Fuller Theological Seminary.

Uniting Church in Australia. 1992. The Basis of Union 1992 Edition. Unley: Uniting Church in Australia.

Uniting Church in Australia. n.d. Minutes of the Queensland Synod 1977–1987. Trinity College, Queensland.

Uniting Church in Australia National Assembly. 2012. The Ministry of Lay Preacher: Report of Review Findings. Adelaide: Ministerial Education Commission.

Uniting Church in Australia. 2018. Basis of Union, Constitution and Regulations. Uniting Church in Australia.

Related articles

![Alan Demack_judge Figure 3: Justice Demack, Supreme Court of Queensland [date needed, and confirm correct wording of title] (Demack family).](https://qareligion.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Alan-Demack_judge-e1689214068556-814x1024.jpg)