A Modern Medievalism: the Abbey Church, Caboolture

An unusual fusion of Christian mysticism, spiritual curiosity, and medieval heritage marked the career of Englishman J.S.M. Ward. Three generations later, the abbey he founded in England in 1930 continues to facilitate multi-faith and community-building efforts in and beyond the Moreton Bay region.

By Geoff Ginn

This is a 20 minute read, published December 2024.

On a busy weekend every year in July, a logjam of traffic fills the road from Caboolture to Bribie Island almost to a standstill. The Abbey Medieval Festival promises an immersion into the world of the Middle Ages, with jousts, feasting, falconry, swordplay, jugglers, minstrels, and more. Whimsical ladies of Shalott embrace clanking knights in armour as Australia’s largest medieval re-enactment event swings into action. Run annually since 1988, the Abbey Medieval Festival is a historical role-playing extravaganza attracting up to 30,000 visitors into the Moreton Bay region with significant boosts to the local economy.

The Festival raises funds for a small but dynamic museum of world civilisations, the Abbey Museum of Art and Archaeology, itself one of the marvels of the Moreton Bay region. Its galleries contain Old Master artworks, illuminated manuscripts, precious artefacts, weaponry, pottery, glassware, coins, statuettes, ceramics: a remarkable artistic ‘pageant of the ages’ that feels to the visitor like a corner of the British Museum. The Abbey Church nearby holds Australia’s finest collection of medieval stained glass, with dazzling colour and masterful heraldic detailing (Strong, 2020). Alongside the church, behind a hedge with shaded verandas, stands the peaceful residence of the Abbey community.

How did this remarkable assemblage end up on a dairy farm between Brisbane and the Sunshine Coast? Peering behind the pageantry, we find a story of visionary mysticism and dogged perseverance that spans three generations and the dominions of the British Commonwealth. From London to Cyprus in the 1940s and finally to Australia, the remarkable story of John Ward’s Confraternity of the Kingdom of Christ and its Abbey adds an intriguing dimension to religious life in contemporary Queensland.

Introducing the Abbey

The Abbey community is a modern expression of a very old idea in religious practice. Its members live in contemplative withdrawal, renouncing things that others take for granted. Like the monks and nuns of medieval Europe, they willingly adopt a mode of living that is thoughtful and austere, with daily routines that ensure time for prayer and meditation. ‘Community members strive to live a balanced life’, the Abbey’s website explains, revolving around ‘attending Church Services, devotion and personal prayer and the practicalities of everyday life.’ Confraternity members have responsibilities in their church, farm, primary school and museum: ‘Holding public services, visiting the sick, undertaking works of charity and giving public lectures form part of the ongoing work of the Confraternity members’, the website explains.

It is a Christian community, but with some important differences. Father George Cuffe, the bishop of the Abbey Church today, explains the essential idea that motivated the founders of the community in England in the 1930s:

The idea was that not only were all people equally beloved by God, but there were different pathways to the divine, different religions, which all were worthwhile pathways to God … it wasn’t just Christianity, but the other great religions of the world were equally as important, and could lead people to an understanding of things of God, and to lead people on the right pathways (Cuffe, 2021).

This idea was a central message promoted by the Reverend Father John Ward (1885-1949), a talented and eccentric Englishman with a lifelong curiosity about antiquities, human culture, and the traditions of spiritual wisdom found around the world. These ideas were key themes in public lectures Ward delivered in London in 1929 to a small but eager and interested audience, that led directly to the founding of the Confraternity and its Abbey.

Who was John Ward?

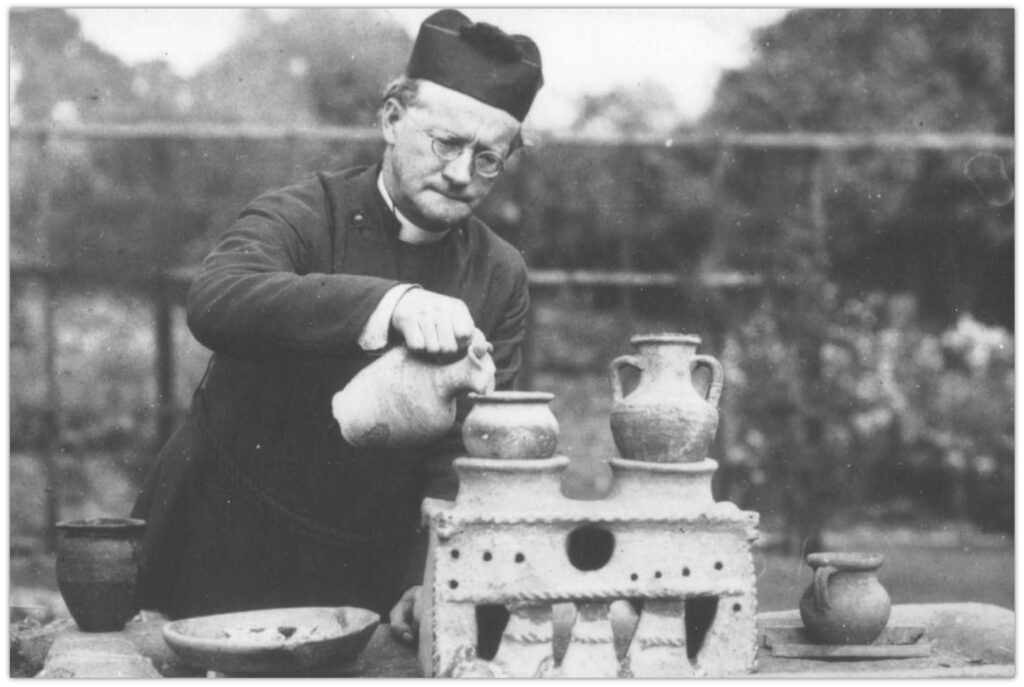

A Cambridge history graduate with a lifelong delight in collecting antiquities, John Ward came to prominence in the 1920s as a prolific author on Freemasonry. Many of his books on Masonic themes, practices, and symbols remain in print today.

He was also a committed Spiritualist, dedicating his adult life to esoteric study in mysticism and comparative religion while working as a schoolteacher and later an economic analyst.

Entitled ‘Life’s Problems’, a set of lectures Ward delivered at a London restaurant in 1929 aimed to inform listeners about the great mysteries of life, death and the afterlife by drawing on a range of religious beliefs. His teachings were essentially syncretistic, infusing Buddhist and Hindu conceptions of karma and reincarnation into western Christian traditions (Ginn, 2012: 122–36).

Others of his day — from Theosophy’s Madame Blavatsky to American ‘New Thought’ figures like R.W. Trine — offered similar fusions of religious belief for Western readers and adherents. But John Ward’s view of a spiritually-infused cosmic reality that constituted and yet transcended ordinary human history and perception was more vivid and lively than most. He had a powerful historical imagination, trained through his studies at Cambridge University, which became increasingly centred on esoteric traditions such as Freemasonry and mysticism. An insatiable collector of historical artefacts and curiosities, his first museum had been started in the attic of his family home when he was only ten years old. As a practicing Spiritualist and a published author on spiritualist themes, he also felt he had experienced genuine personal revelations through clairvoyance of the realities of the ‘spirit plane’, precipitated by the death of his brother in the Great War.

By the late 1920s Ward and his wife Jessie felt they had a divinely-inspired mission to prepare for the Second Advent — the return of Jesus Christ. Through shared visions and mystical experiences, they were convinced they had been given messages that Christ would return as an earthly king, to deliver a new spiritual dispensation amid the catastrophic collapse of the existing world order. Like many, they felt these ‘signs of the times’ were increasingly evident as Britain and Europe staggered through the economic and political turmoil of the interwar years.

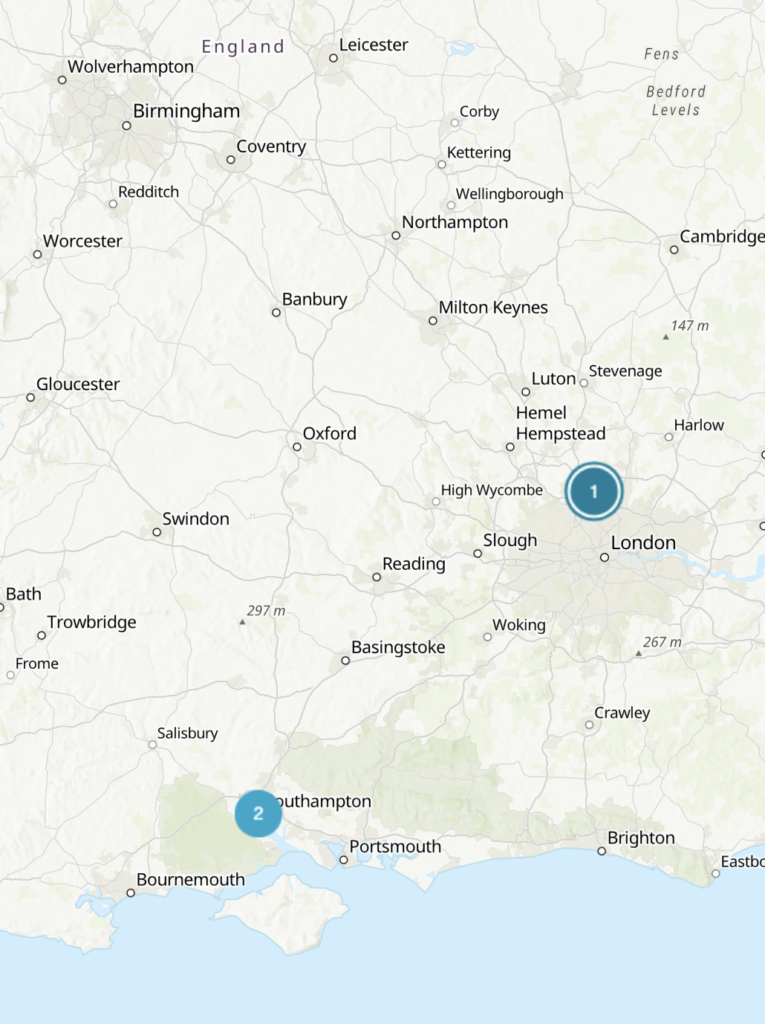

Delivering this millenarian message was the purpose of Ward’s 1929 public lectures. Among those who came to listen there were around a dozen men and women who then decided to join the Wards in preparing for this sacred advent. With John Ward’s antiquarian enthusiasm and a deliberate sense of their defined historical mission, they together formed the Confraternity of the Kingdom of Christ, an intentional community with a character perhaps best described as High Church Anglicanism leavened by both a pan-religious philosophy of spiritual evolution and a millenarian zeal (Ginn, 2012: 136–46). Ward was himself the son of an Anglican clergyman, and as a patriotic Englishman valued the historical significance of the Church of England very highly. Together the dozen or so members of Ward’s new Confraternity purchased a large house, Hadley Hall, in New Barnet, north London, as their communal dwelling.

Taking solemn vows and agreeing to share their worldly possessions, they committed to live in simplicity in a common life on the model of a medieval monastery re-configured for modern times. Some were married couples when they joined, while others met and married their spouses within the community. Along with the Wards, the early Confraternity members came from a number of families such as the Cuffes, the Strongs, the Balls, and the Chamberlains. In time, their children were brought up within the community and many, like George Cuffe today, remained members throughout their adult lives.

In the mid–1930s, following a rift with the Anglican bishop of nearby St Albans, Ward sought to cut ties with Anglicanism. In a sign of the importance that religious and ecclesiastical tradition had for him, he settled on the autonomous Orthodox Catholic Church in England, a small group within the independent sacramental movement, led by Archbishop John Churchill Sibley. Claiming a succession of holy ordination and consecration through a line of bishops, one after the other back in time to the original apostles, these episcopi vagantes had been a feature of Christian life for centuries. They experienced a remarkable revival in the nineteenth century around the world. Often dismissed as mischievous cranks by the religious mainstream, such bishops often revelled in elaborate titles and vestments, favouring archaic rituals and ecclesiastical privileges.

Figure 4: Interior of the Abbey Church (Confraternity of the Kingdom of Christ), New Barnet, c. 1930s (Abbey Museum).

When John Ward joined their ranks, ordained by Sibley and then consecrated as a bishop in 1935, he brought with him his distinctive blend of historical imagination, profound Spiritualist convictions, and a pan-religious interest in the great mystical traditions of the world and their common heritage (as he saw it) of spiritual teaching (Ginn, 2010a). For Ward, this was not a shallow exercise in showy titles. Rather, his adoption of Sibley’s ‘Orthodox Catholicism’ — seen by adherents as a literal reconciliation of eastern and western modes of Christian practice, sundered since 1054 — was a considered and deeply-felt commitment, one that corresponded to both his historical intelligence and his perennialist philosophy of esoteric knowledge.

Around this time, too, Ward and his community established a remarkable small museum in their grounds at New Barnet. Known as the Abbey Folk Park, this became well-known as a vivid and realistic recreation of the social history of different historical periods, from prehistoric cultures to the great world civilisations.

Here visitors learnt the true meaning of human history, as Father Ward saw it: with spiritual evolution, all societies and cultures rose and fell, in a vast panorama of human effort and achievement that left its mark in the everyday items and artefacts Ward gathered together in his museum.

Leaving England, into exile

The eruption of war in 1939 changed everything for Ward and his community. As Europe plunged into conflict and the British nation bunkered down, the Abbey Folk Park was closed to visitors. The Abbey itself continued, with a new sense of purpose in grim times. In 1941, the Ministry of Labour recognised Ward’s tiny confraternity as a religious institution (something major church bodies had not done), and treated its members as being in a ‘reserved occupation’ and thus exempt from conscription.

Then, abruptly, the life of Father Ward and his Abbey was swept into a disastrous family dispute involving Dorothy Lough, a local teenager at odds with her parents. A strong-willed and religious girl, Dorothy had attended services and classes at the Abbey and was often placed in the Ward’s care during holidays and times of family difficulty. But as her family relations deteriorated and matters escalated into legal action, the Wards were accused of maliciously enticing Dorothy away from home as a recruit into their order. The quarrel climaxed in a sensational case in the High Court of Justice over two weeks in May 1945. In the common law at this time, ‘enticement’ generally referred to seduction; the use of the term helped to miscast the proceedings as a ‘morals’ case in the British national press.

The courtroom spectacle was arresting: an eccentric, other-worldly Father and Mother Superior, on trial (it seemed) for irregular behaviour behind the closed doors of modern abbey admitting disaffected children and married couples alike. Readers of the daily newspapers were enthralled over ten days of legal drama in the ‘Sister Terese Enticement Case’: accusations and denials, claim and counter-claim (Ginn, 2012: 228–52). The presiding judge later remembered it as one of the most unusual of his long career, but his decision in May 1945 — that Sister Terese, then aged 18 but still legally a minor, should leave the Ward’s premises and return, against her will, to her family — was devastatingly clear-cut.

Meanwhile, the tabloid sensationalism that enveloped the proceedings savaged Father Ward’s reputation beyond repair, damaged his health and led directly to the community’s decision to leave England in 1946. Ward’s conviction that British national life (and European civilisation more broadly) was in terminal decline aligned with an acute public humiliation: it was time to leave England forever.

The Confraternity travelled initially to Cyprus, moving into a large house with an orange orchard they purchased at Germasogeia near Limassol. Here they attempted to survive as a self-sufficient religious community, acutely aware that they had taken themselves ‘into exile’.

Father Ward died of a stroke there in 1949, to the anguish of his wife and followers. With further privations and Cyprus’s slide into terrorism and civil war in the mid-1950s, his community (now led by Ward’s widow, Jessie and with a second generation of young children) travelled to Australia via Sri Lanka and India.

Arriving in Sydney, they settled at Blackheath in the Blue Mountains. Despite the London court’s injunctions of 1945, ‘Sister Terese’ remained with them, identified as Mrs Lillian Knight on her passport but now known as Sister Nina. In the mid-1960s, following an earlier visit to Queensland and facing her own health problems, Jessie Ward decided to move the community north. Tragically, Sister Nina died suddenly in January 1963 after an internal haemorrhage linked to chronic ulcers and refusing a blood transfusion (Ginn, 2012: 257–65). Jessie Ward herself passed away in February 1965, leaving Sister Mary (Joan Mary Strong) as her successor.

To Caboolture: building a community of faith

The Confraternity of the Kingdom of Christ, now numbering around twenty members from the original group of families, purchased a 127 hectare property near Caboolture in July 1965 which they named ‘St Michael’s’. The commitment to a self-sufficient communal life continued, and to begin with it was simple hard work establishing the new farm and its enterprises: “a harsh drought season, every known local crop-attacking bug, heat the likes of which none of the predominantly English had ever known. But they persisted, and between ploughing, water carrying and bug fighting, they got on with the other duties of a Christian community.” (Mackay, 1977: 27) A dairy herd was established, butter and cheesemaking commenced, along with pigs, cattle, beekeeping, and small crop farming particularly tomatoes and pumpkins.

Community members today recall the early pioneering years in Caboolture as a time of purposeful activity, with a rewarding routine of work and quiet contemplation interspersed with camaraderie and good humour. George Cuffe, born in Cyprus in 1951 and later a fully professed member of the community from 1976, describes an ordinary day:

It was run fairly strictly in the sense that we rose in the morning to the sound of a bell at 5.30, we had a morning service and then we went and did work in different areas … I chopped firewood for half an hour before breakfast, we had breakfast at 6 o’clock and then we had our main morning Office [a religious service] at 7 o’clock, and then we had a work meeting as to what work needed to be done that day … mainly on the farm at that stage because we needed to be self-supporting and self-sufficient, like the ancient Benedictine monasteries we were growing our own food mainly, and working on the farm to produce what we needed and also to sell any excess produce (Cuffe, 2021).

The rest of the day followed a similar pattern, with morning tea, lunch and a midday service, work into the evening until 6 pm, evening Office at 7 pm, and a traditional Vespers service in the Abbey Church at 9 pm.

An abbey needs buildings to function: the everyday requirements of kitchens and sleeping quarters as well suitable spaces for religious services and worship. The prosaic tasks of building and construction thus took priority, the first being a church.

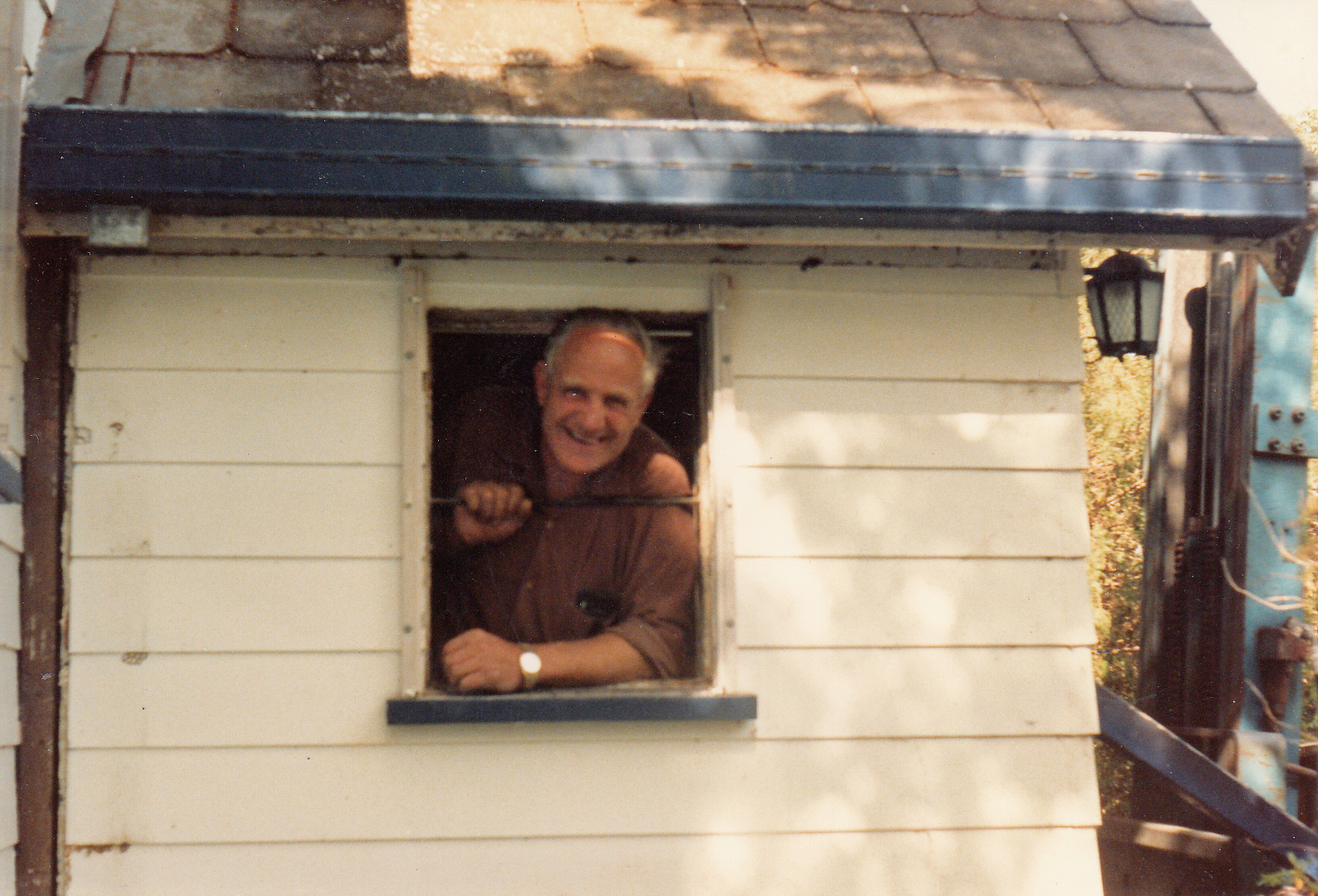

In 1967, a derelict fish and chip shop in nearby Morayfield was salvaged for scrap materials, and combined with recycled timber from a demolition yard in Virginia to build the first Abbey Church. The effort was led in person by Father Francis, assisted by the community’s brothers.

An approachable and friendly Englishman, big-hearted with an energetic presence, Father Francis later became Archbishop of the Abbey Church and one of the leaders of the community. He is remembered as an impressive figure, willing to share in the farm work feeding pigs and milking cows, conducting baptisms and celebrating weddings, attending the sick and dying, often all on a single day. “He was always at hospitals,” Sr Veronica remembers, “People knew that if they needed a priest at a time, they could ring Father, he would go, we often heard the van racing out in the middle of the night because someone needed help” (Cuffe and Ruygrok, 2023).

For over thirty years until his death in 2000, Father Francis was a well-known local figure, able to reach out and extend help in a very personal and practical way. His love for football saw the English game introduced to Caboolture through the St Michael’s Soccer Club, the beginnings of a local soccer competition which now has over a hundred junior and senior teams (Cuffe, 2021).

Reverend Mother (as Mary Strong was universally known) was a different type of English expatriate, a more reserved figure concerned with maintaining the community’s traditions. If her default position was likely to be “this is the rule, this is how we did it in England” (Cuffe and Ruijgrok, 2023), she was also a person of quiet authority and spiritual depth. She worked hard in the interests of the tight-knit community, taking her share of physical duties on the farm, and her devotion to its way of life continued until her passing in 2012.

By the mid-1970s the hard work of founding their abbey was complete, and the membership of Confraternity of the Kingdom of Christ peaked at around 25 as a second generation of members reached adulthood. A small, hardworking and somewhat separate community — despite Father Francis’ personal outreach and social presence around Caboolture — they worked together in the fields, gathering daily for prayers and Holy Communion. In the evening Office services they sang Ward’s poetic hymns by candlelight in their small, transcendent chapel, hung with centuries-old paintings of Christian themes as the windows glittered with mediaeval stained glass. The spiritual essence of a medieval abbey, charged with a modern mysticism that saw truth in other faith traditions, had been successfully transplanted to a Caboolture dairy farm.

Opening up

The hard work of establishing the Abbey’s basic facilities was followed by a substantial expansion of the scope of the community’s work in the 1980s. At that time, independent schools were rare in Queensland, and the National Party’s conservative Education Minister Lin Powell was keen to encourage small independent faith-based schools. Nevertheless, it was a daunting prospect, despite the community’s experience in this area going back to the small school known as St Michael’s College they had run in England and the fact that many of Ward’s original members (including Ward and his wife Jessie) were teachers.

As Sr Veronica remembers it today, the initial impetus was provided by Peter Jackman, a Catholic educator who aimed to start a Christian high school in the Caboolture area in 1983, with around twenty Grade Eight students in the first intake. However when funds proved a problem and the school closed, the Abbey community – starting with four students in the original farmhouse at the property – began St Michael’s College. The enrolment grew to twenty within the first three years.

As a curriculum was developed and government funds secured, leading to full registration in 1987, the Abbey community drove the effort forward by providing the land for a new campus. Within ten years, three classroom buildings and an administration office, library, and a pre-school facility were constructed. “A lot of the [Abbey] community resources were poured into the school”, she remembers, “people worked in the school … mowing, making resources, it was a real community project” (Cuffe and Ruygrok, 2023).

Forty years after its humble beginnings, St Michael’s College today is a highly-regarded local primary school, with Early Learning and OSHC centres, a performing arts complex and IT lab with an enrolment over 360 students. Students attend weekly chapel services throughout the year.

Figure 11: Aerial photograph, Abbey Church, Abbey Museum, and farm, 1991. The college and Abbey Medieval Festival site (not pictured) are situated to the upper right of this image (Abbey Church).

At the same time the school was being developed, the early planning to re-open John Ward’s museum was underway. Among the community’s younger generation, Michael Strong took the lead in conceiving of how Ward’s collection of artworks and antiquities — stored in boxes and tea chests, largely neglected, since their arrival in Australia in the 1950s — might be resurrected as a viable museum. A talented young art historian and archaeologist, Strong galvanised the other members of the community with its focus on the daily work of the farm to consider the future of their precious artefacts.

By the mid–1980s, cataloguing and storage improvements had commenced and a grant secured through the Utah Foundation to construct a purpose-built venue close to the Abbey Church. It opened with fanfare in June 1986 as the Abbey Museum of Art and Archaeology, followed two years later by the first Medieval Tournament held as a fundraiser for the new museum. Attracting families and enthusiasts to the educational experience of medieval role-playing, the success of the Abbey Medieval Festival ever since has promoted awareness of the Abbey, its church and community throughout Queensland and further afield.

The Abbey community today

Although the permanent residents have dwindled to only a small handful, the Abbey retains its spiritual and communal commitments as a local centre of faith and compassion. Today, inter-faith work in Caboolture has its home at the Abbey Church, which was formally constituted as a Multifaith and Cultural Dialogue Centre in August 2018. Their chapel continues to welcome all to weekly Sunday services, celebrating weddings and baptisms, as well as funerals and memorials services to console the bereaved. The thought-provoking lyrics and rousing melodies of Ward’s hymns are sung as the bright Queensland sunshine streams through the medieval stained glass of the Abbey Church.

… bringing that sense of acceptance and non-judgement and being more Christ-like in the way we live and treat others … we’re looking at what real community is all about

From esoteric Adventists to pillars of the local community, the journey of the Abbey community has negotiated a path from outsiders to insiders. The mysterious beliefs and quaint neo-medieval practices of the early days were a source of local bemusement, but this has given way to an avid enthusiasm for what the modern Abbey community at St Michael’s community represents. For Sr Veronica, there is an underlying continuity despite the changes, that links the Abbey’s present with its past. “It was definitely the passion,” she says,

that we were all working for the King, you know, and [that] was the return of Christ. And I think that nobody knows what the future will hold … [but] if we all work for peace, and see Jesus in every person, it’s almost like we are bringing Jesus to the earth, whether that’s in a metaphorical way or its going to be in a second coming, I don’t know … As we’re changing into a broader community, with intersecting circles in the wider community, and even global community, bringing that sense of acceptance and non-judgement and being more Christ-like in the way we live and treat others … we’re looking at what real community is all about (Cuffe and Ruijgrok, 2023).

With thanks to Father George Cuffe, Sister Veronica Ruygrok, Michael Strong, Edie Cuffe, Miriam Cuffe and other members of the Abbey community. Disclosure: the author was a member of the Board of the Abbey Museum of Art and Archaeology, 2013–22, and its chair in 2017.

Sources and further reading

Cuffe, George. 2021. Interview, Parts 1 and 2, Abbey Church, 13 April 2021.

Cuffe, George and Ruygrok, Veronica. 2023. Interview, Abbey Church, 3 October 2023.

Ginn, Geoffrey. 2010a. ‘J.S.M. Ward, ‘Bishop at Large’: ‘Orthodox Catholicism’ and Church History in Interwar Britain.’ Crossroads 5, 1: 45–57.

Ginn, Geoffrey. 2010b. ‘An Ark for England: esoteric heritage at J.S.M. Ward’s Abbey Folk Park, 1934-1940.’ Journal of the History of Collections 22, 1: 129–40.

Ginn, Geoffrey. 2012. Archangels & Archaeology: JSM Ward’s Kingdom of the Wise. Brighton: Sussex Academic Press.

Mackay, Diana. 1977. ‘Splendid Treasures in the Bush’, Australian Women’s Weekly 11 May. pp. 26–7.

Ruygrok, Sr Veronica. n.d. ‘History’ [St Michael’s College] https://smccab.qld.edu.au/.Viewed 11 April 2024.

Strong, Michael. 2020. Glorious Glass: Stained Glass in the Abbey Museum Collection. Caboolture: Abbey Museum of Art and Archaeology.

Ward, J. S. M. 1944. The Orthodox Catholic Church in England, Showing its History and the Validity of its Orders. New Barnet: The Abbey of Christ the King.

“History of the Confraternity | Abbey Church | St Michael’s Community.” Abbeychurch.com.au, 2021. https://abbeychurch.com.au/history-of-the-confraternity/. Viewed 25 February 2021.

Related articles