Smells and Bells: Anglo-Catholicism at All Saints', Wickham Terrace

Located in the heart of the Anglican diocese of Brisbane, All Saints' was consecrated in 1869. Since that time it has been an important focal point for the Anglo-Catholic tradition in Queensland.

By Philip Almond

This is a 15 minute read, published June 2024.

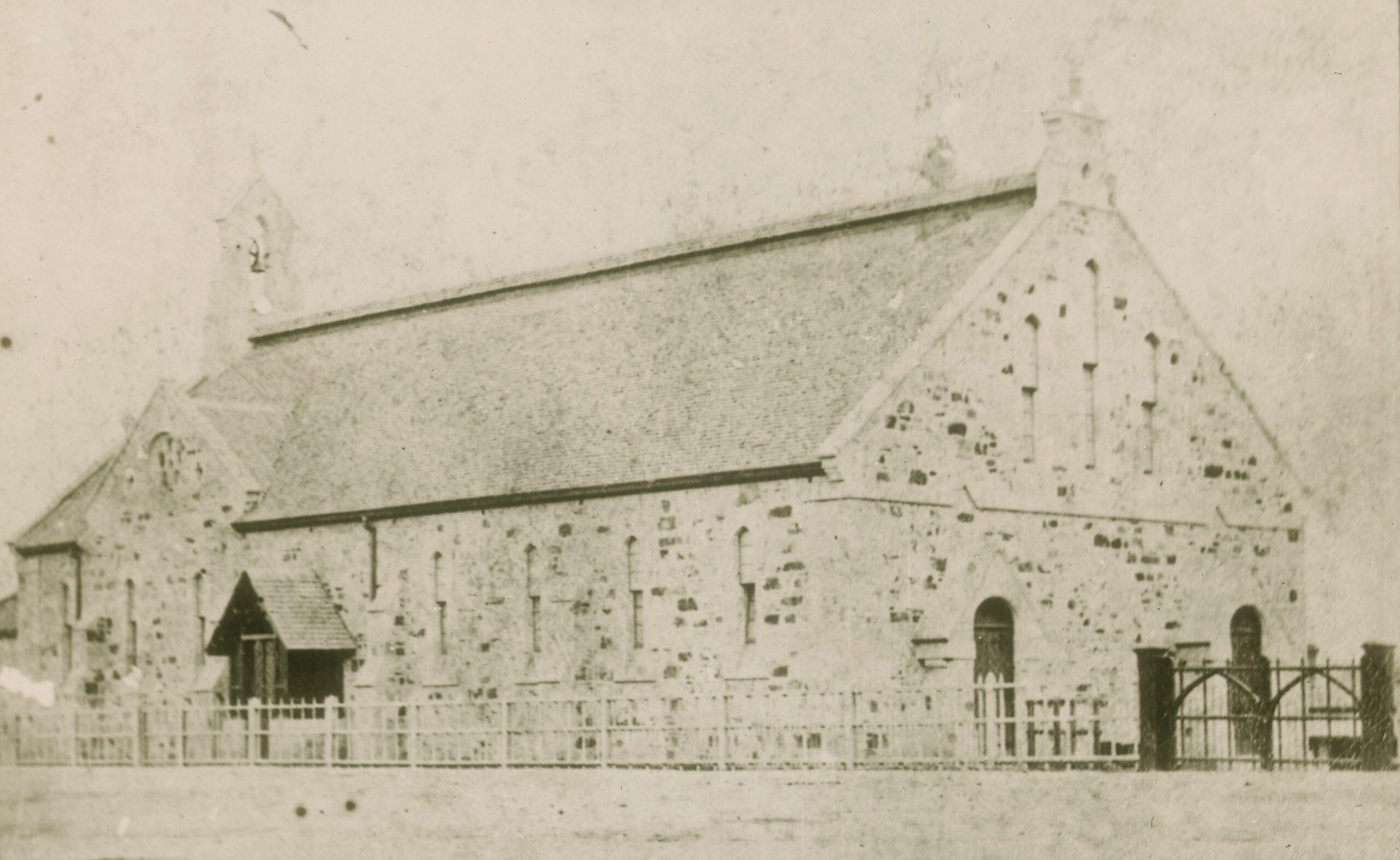

All Saints’ Anglican Church is the oldest Anglican church in Brisbane. The first service was held in the newly constructed church on September 8, 1869, the feast day of the Nativity of the Virgin Mary, replacing the Wickham Terrace Church of 1862. The first Bishop of Brisbane, Edward Tufnell, named it ‘All Saints’ (The Courier, March 31, 1869). The name indicated that it was intended as a colonial outpost of the movement in the Church of England known as ‘Anglo-Catholicism’.

This was an outgrowth of the nineteenth-century Oxford Movement that sought to re-establish ‘Roman Catholic’ thought and especially practices in the Church of England — the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, devotion to the Virgin Mary, the wearing of ecclesiastical vestments in liturgy, the use of incense, private confessions, the revival of monastic orders, the succession of the priesthood from the apostles of Christ, prayers for the dead, the preference for a celibate clergy, and the intercession of the saints to God on behalf of those who sought their help. As David Hilliard notes, the spread of the Oxford Movement in Australia, as elsewhere in the Anglican world, in the second half of the nineteenth century ‘amounted to a liturgical revolution’ (Hilliard, 1994: 5).

The Anglican church began in 1534 when Henry VIII ambiguously embraced Protestantism so that he might bigamously embrace Anne Boleyn. Breaking away from the Catholic Church, Henry became Head of the Church of England, a position still held by King Charles III. Thus began the struggle for the identity of the Anglican church as it lived out the tension between its Calvinist Protestant beginnings and its Catholic roots.

The Anglo-Catholic movement re-established the importance of the saints in the prayers and liturgy of the church. So, the title ‘All Saints’ gave a clear signal of the new church’s commitment to the Anglo-Catholic or ‘high church’ (as opposed to the Protestant ‘low church’ Anglican tradition). All Saints’ remains still the key location for the practice of Anglo-Catholicism within the archdiocese of Brisbane.

They go Low but we go High

Bishop Edward Tufnell sailed up the Brisbane River to arrive in Brisbane on September 2, 1860. He came to a colony where the non-conformist churches disliked bishops on principle and the low church Anglicans were suspicious of his high church principles and his commitment to the importance of the sacraments, the virtues of decorated churches, beautiful vestments, high ceremonial, and church music. The non-conformist Brisbane newspaper, The Courier, made its feelings clear: ‘we do not know that there was any necessity for such an appointment. What there is at present to be Bishop of we do not know. In England the Bishops live on the fat of the land, dwell in palaces replete with earthly splendour, and endeavour in the House of Peers, to constitute a spiritual tyrranny [sic] against which the millions rebel … Surely England might leave her children, settled so far away, to do as they please’ (Rayner, 1963: 84).

Regardless, Tufnell appointed clergy with high church leanings and All Saints’ came quickly to exemplify the high church leanings of the bishop. A sermon preached on the day of its first service by the Reverend John Sutton indicated the direction it was heading: ‘You know the feeling that has been growing up lately for splendour and decoration in the service of God. It may be running wild here and there, but it is not to be despised or condemned. Thoughtful men knew that it must be so years ago, apart from its being right or wrong, for there would be a reaction upon the abominably cold, slovenly, barn like appearances of places of worship’ (Kissick, 1937: 137).

But the battlelines between high and low at All Saints’ were soon to be drawn. Thomas Jones had been appointed priest of the Wickham Terrace Church on January 1, 1865. An avowed Anglo-Catholic, he had accompanied Bishop Tufnell to Brisbane and became, in 1861, the first Anglican priest to be ordained in Brisbane. He was part of an Australian trend. As David Hilliard notes, ‘Young clergy with definite Anglo-Catholic views were often attracted by the romantic prospect of planting the full Catholic faith in the colonies, without the restrictions they encountered at home’ (Hilliard: 1993, 9).

On May 21, 1865, Thomas Jones preached a sermon in which he declared that ‘suffering is ever a part of the dispensation of the good Providence of God’ (Kittrick, 1937: 129). Suffering soon came his way. He was attacked in the press for his Anglo-Catholic ways — facing East during the celebration of the Eucharist, using the Salisbury hymnbook (especially hymns with reference to the Virgin Mary), placing candles on the altar, having crosses marked on articles in the church (see Kittrick, 1937: 37).

Thomas Jones was always likely to create controversy among more Puritan-minded Anglicans. He was happy to umpire cricket games on the Sabbath with his friend John Sutton, and preferred to go to the theatre than attend meetings of the Bible Society. The discontented at All Saints’ began to mobilise. And in 1868, the low church opponents of Jones left the church to join the ‘Free Church of England’, ‘a refuge to members of the Church of England from the ritualistic and rationalistic tendencies of the established church at the present day’ (Rayner, 1962: 136; Daw, 1975: 3).

Thomas Jones was Anglo-Catholic to the core. The right path for the Church of England, he declared in a sermon, was to avoid ‘the extremes of Puritanism on the one hand and the errors of the Papacy on the other’ (Kissick, 1937: 132). He remained parish priest at All Saints’ until 1878. Rarely, for All Saints’ clergy, Thomas Jones was married. Until Peter Bennie became parish priest in 1953, all the priests in charge of All Saints’ after Jones were celibate.

The Anglo-Catholics seemed to be in the ascendancy by the end of the nineteenth century. ‘If a man was Protestant’ in Brisbane, claimed a member of the Anglican Church in the diocese of Sydney, then as now the most low church of Australian dioceses, ‘he had no place’ (Hilliard, 2010: 111).

An Anglo-Catholic Modernist

For All Saints’, it was a crisis. In 1911, Archbishop of Brisbane St Clair Donaldson asked its parish priest Douglas Price to resign. Despite vehement protests from his parishioners, Price complied. Donaldson had no doubt wanted to be rid of this turbulent priest for some time. In 1909, Donaldson proposed to a special meeting of the congregation that the land and church be sold, and the congregation join that of the nearby cathedral. Donaldson intended the funds to be used for building the cathedral. Price and his congregation were having none of it. The motion that the church continue without change won by 200 votes to nine. So, Donaldson found another way. He requested copies of Price’s sermons, found evidence of unorthodox teaching (not unreasonably), and moved him on. Price moved but, as we know, the church stayed.

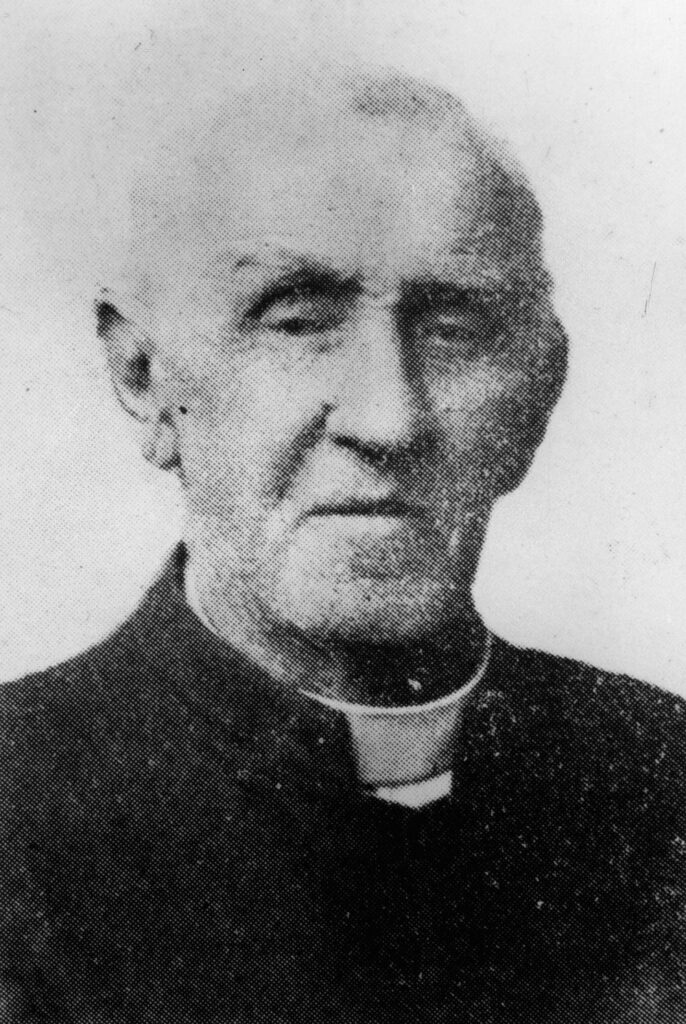

The Reverend Douglas Price had arrived in Brisbane in 1903 to take up a position as lecturer in the Anglican theological college. He became Rector or priest in charge of All Saints’ on February 5, 1905. Price was part of the nineteenth-century Modernist movement in the Church of England, a movement attuned to adapting Christianity to the modern world. Price defined it as ‘the new spirit in religion which welcomes all the truths of science and criticism and seeks to restate the old faith in accordance therewith’ (Ralston, 1920: 9).

Conservative in the theology around sacraments and ecclesiology, Anglo-Catholicism could be liberal in matters theological more generally. And Price was nothing if not liberal. Gradually, he tells us, during his time at All Saints’, the doctrines of the Trinity, the Atonement, the Virgin Birth, the Resurrection, and the Deity of Jesus slipped away from him. In keeping with his Quaker heritage, religion had become more a matter of aesthetic and ethical inwardness than doctrinal orthodoxy. ‘If love, justice, goodness, beauty, and truth be not God, that word has no meaning for me. God is our highest ideal; the devil is our own stupidity and vileness’ (Ralston 1920: 10). The Bible? It was for Price the literature of the whole world. He was to drift towards the Unitarians and the Theosophists, and generally to what we would now label ‘new age’ ideas.

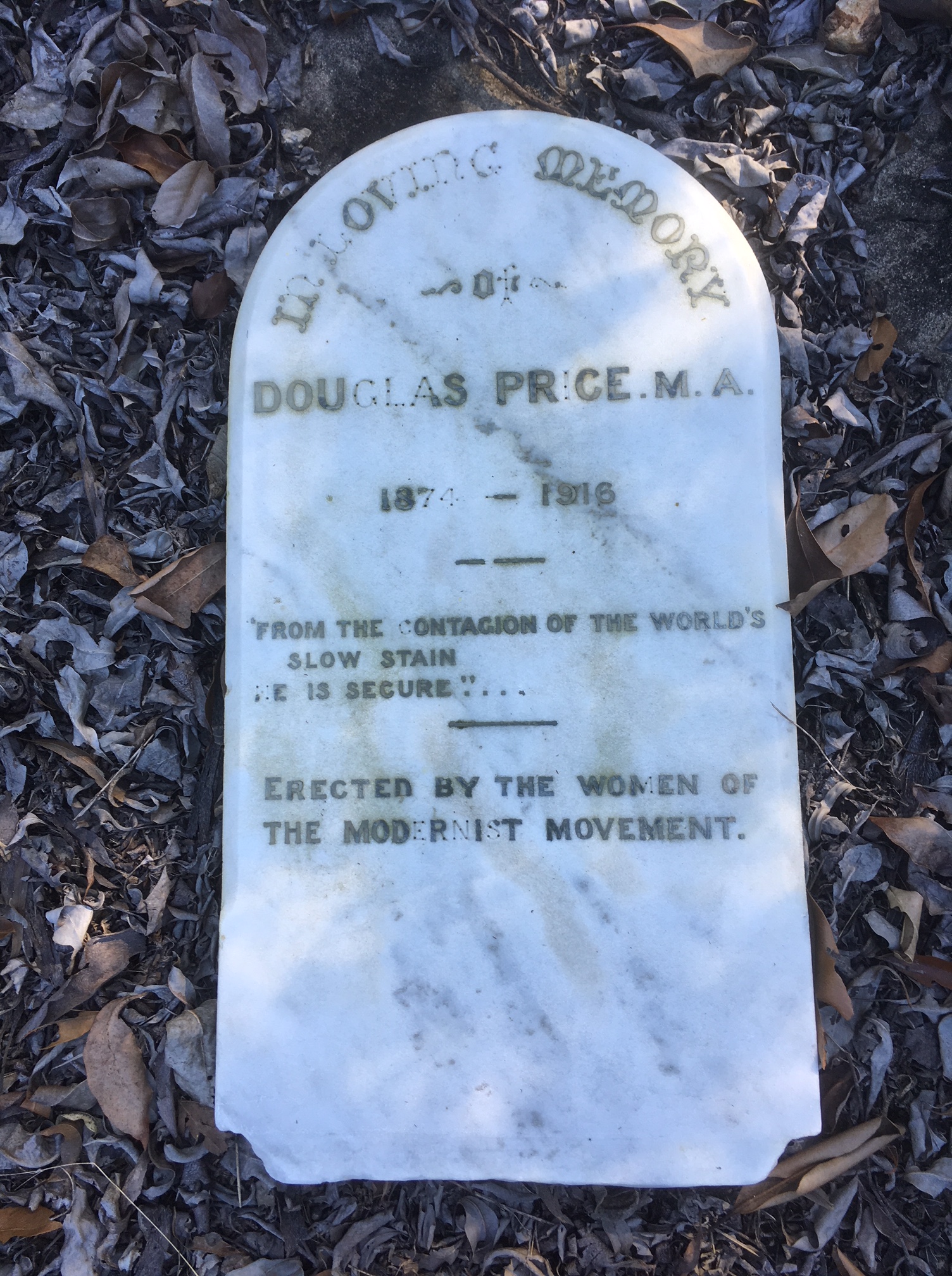

After leaving All Saints’, Price went on to create the Brisbane movement known as ‘Progressive Christianity’ and the ‘Modernist Movement’, the first meeting of which took place on December 4, 1911. He took many of the All Saints’ parishioners with him. Its first President, Dr A. Jefferis Turner, wrote in the journal of the Society that the membership comprised ‘Christians and Theosophists, Spiritualists and Rationalists, Sceptics, Agnostics and queer sorts of Dogmatists, and cranks of all sorts’ (Granville, 2018). He died in 1916, probably from a self-inflicted injury. The epitaph on his gravestone, ‘erected by the women of the Modernist Movement’ in South Brisbane Cemetery, quotes the elegy of Percy Bysshe Shelley on the death of John Keats: ‘From the contagion of the world’s slow stain, He is secure.’

A very English Catholicism

The Anglo-Catholicising of All Saints’ continued in the early 1920s under the direction of the Reverend Farnham E. Maynard who became parish priest on 1 August 1922. For the next four years, he was an activist, liturgically and educationally, both inside and outside of All Saints’. When he was asked by Archbishop Gerald Sharp to accept the position of priest there, he indicated that he would want to make several changes. On being asked what they were, he replied, ‘Well, first of all I will want to introduce the use of incense and then I shall want to reserve the Blessed Sacrament.’ ‘Anything else?’ the Archbishop asked. ‘I think that will do for a beginning,’ Maynard replied (Kissick, 1937: 104).

It was only the beginning. For, over the next four years, communion services were made to conform with ‘Ritual Notes’, the ‘English Hymnal’ was introduced, a crucifix was introduced to the church, a tabernacle was built in the Lady Chapel to house the ‘reserved sacrament’, High Mass was said and sung every Sunday, and the ringing of the Angelus bell was begun.

Only socialism, Maynard believed, could provide the economic foundation for the Kingdom of God.

To go with his Anglican faith, Maynard brought from England a commitment to Christian socialism and a ministry to the poor. Like many Anglo-Catholics, his was a social gospel. Christians were to create a heaven on earth through social action. In 1924, he introduced Christian Evidence lectures to the people of Brisbane: ‘Does Religion Conflict with Science?’; ‘What is the Bible?’; Did Jesus Rise From the Dead’? ‘The Christian Idea of God’; and ‘Miracles’. Only socialism, he believed, could provide the economic foundation for the Kingdom of God (Pear, 2016: 18). As he was later to write, ‘There is a… vital relationship between the Economics of the World and the Kingdom of God. The author’s [Maynard’s] main purpose is to arouse both the understanding in and the conscience of Christian laymen to a recognition of this fact’ (Pear, 2016: 21).

There was much rumbling about Maynard from conservative low church Anglicans. In 1924, a body called ‘The Church of England Defence Association’ unsuccessfully moved that the Synod ‘deeply regrets the spread of extreme Anglo-Catholic Teaching and Practice in this Diocese.’ Archbishop Sharp hosed down (although not with ‘holy water’) the dissidents — at least, for a while (Hilliard, 2010: 110).

Ever fearful that Anglo-Catholics were only ever a short step away from collapsing into the arms of the Pope, three Anglican conservative lawyers in Brisbane began another battle against the worship and practices of Anglo-Catholics in 1953. Peter Bennie, the then priest of All Saints’, had to put up with the three sitting in All Saints’ taking notes in preparation for presenting their case to the diocesan Synod. Bennie labelled them the ‘three blind mice’: ‘They see nothing, hear nothing and know nothing.’ The attack collapsed.

Despite the fears of the conservatives, the Anglo-Catholic movement was staunchly English and not inclined to conversion to Rome. Farnham Maynard was deeply offended by Roman Catholicism’s denial of the validity of the Anglican priesthood and thus of the validity of the sacraments administered by Anglican priests. Maynard regarded Papalism as uncatholic. It was ‘a fruitful cause of evil in the Church.’ The Roman church was an intrusive ‘Italian mission’ to the ancient Catholic tradition of the Church of England, he believed, (Hilliard, 1994: 19). So too did Peter Bennie, who had no doubts about the true Catholic nature of the Anglican tradition. The Anglican tradition,’ he wrote, ‘is a living witness that Catholicism is a wider, deeper, more truly universal thing than it has hitherto been presented to the world.’ The Catholic church, he went on to write, ‘does not appear in her most impressive guise in the bearded and balkanised peasantry of Eastern Europe, nor for that matter in the grave cloths of the Roman Empire’ (Moses, 2011: 10).

The Monstrous Regiment of Women Priests?

On 24 May 2005, the Archbishop of Brisbane, Phillip Aspinall, removed David Chislett from his position as the parish priest of All Saints’ where he had been priesting for ten years (Gau and Arlo, 2007: 139–41). The underlying cause of his sacking was his vehement opposition to the ordination of women within the Anglican Church of Australia.

In the Australian Anglican church, as elsewhere, the opposition to the ordination of women to the priesthood came from the conservative High and the conservative Low ends of the church. At the Low church Protestant end, the argument was biblical. Jesus had only chosen men to be his apostles. At the Anglo-Catholic end, the ordination of women was held to be against two thousand years of the tradition of the male priesthood, not least because the priest acted in the person of the male Jesus Christ.

The general synod of the Anglican Church of Australia allowed for the ordination of women to the priesthood in 1992, but it was left to individual dioceses to decide whether to allow women to be priests. The Archdiocese of Brisbane ordained six women to the priesthood in December of that year.

By 1992, opposition to the ordination of women at All Saints’, both lay and clerical, was already well under way. Albert Haley, the then parish priest, had formed an organisation in 1985 called the ‘Campaign for the Historic Anglican Male Priesthood’. His opposition was so vehement that he broke away from the Anglican church, left All Saints’, and formed a new Anglo-Catholic church on August 20, 1987, called ‘The Anglican Catholic Church in Australia’. He was consecrated as its first bishop in the following year. His successor at Wickham Terrace, Walter Ogle, also left the Anglican Church to join the Roman Catholic church as a layperson.

In an address to his congregation on February 25, 1996, David Chislett recommended that the parish become a member of the organisation Forward in Faith International, a ‘worldwide association of Anglicans unable in conscience to accept the ordination of women as priests.’ The parish voted overwhelmingly for this affiliation (Cotes, 1997: 308). All Saints’ has maintained its relationship with this organisation.

David Chislett was to follow Albert Haley into the Anglican Catholic Church in Australia, while remaining the priest of Saint Andrews. In February 2005, it was reported to Archbishop Aspinall that, not only had he joined that church, but he had been consecrated as a bishop within it. After a commission of inquiry, the archbishop advised the clergy of his diocese that Chislett had been deprived of his living at All Saints’. Chislett had hoped that he could remain in both churches and that, as a bishop, he would be able, as a ‘flying bishop’, to serve the episcopal needs of those Anglicans in Australia distressed by the ordination of women. It was a forlorn hope. David Chislett died on 12 September 2023.

A Touch of Heaven

Anglo-Catholicism was a revolution in nineteenth-century Anglicanism. It was, on the face of it, about matters of doctrine. But these were progressively expressed in a complex ritual aesthetics. Anglo-Catholic liturgy manifested the divine presence. In the Mass, God became literally present on the altar. He was visibly displayed for worship and adoration in the monstrance in the ritual of Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament. He remained continually present in the Reserved Sacrament in an elaborate tabernacle.

The Australian scholar David Hilliard (2010: 110) has mapped precisely the movement towards Anglo-Catholicism at All Saints’ across the long term:

… altar cross and ornaments 1884 and lighted candles 1893 (the first in Queensland); a celebration of Holy Communion on holy days 1885; eucharistic vestments on weekdays from 1885 and on Sundays from 1903; the observance of All Saints’ Day as the church’s patronal festival 1899; Midnight Mass at Christmas 1903; daily Eucharist for a few years from 1904, resumed in 1918; Choral Eucharist replacing Matins as the main Sunday service 1905; incense 1923; reservation, in a tabernacle in the Lady Chapel 1924; High Mass every Sunday (without communicants) 1925; devotions before the Blessed Sacrament after Evensong 1930s; Benediction c.1960.

The theatre of liturgy at All Saints’, as for all Anglo-Catholic churches, is the essence of religious life. As Stephen Hill put it in 2022, ‘One day I wandered into Solemn High Mass at All Saints’ Anglican church in Wickham Terrace, Brisbane … I didn’t know what an Anglo-Catholic was, and I didn’t really know that much about Anglicanism either, but I knew that it was the most beautiful thing I had ever seen in my life. It was amazing — the Mass, the choir and pipe organ, the servers, clouds of incense; ‘smells and bells’ as they say. I felt like I was in heaven’ (Hill, 2022).

Sources and further reading

Cotes, Alison. 1997. ‘“The Monstrous Regiment”; Anglo-Catholics in Australia since the Ordination of Women.’ In John Moses (ed.), From Oxford to the Bush: Essays on Catholic Anglicanism in Australia. ACT: Broughton Press, 299–316.

Daw, E. D. 1975. ‘The Free Churches of England in Queensland.’ Queensland Heritage 3, 3–6.

Gau, Justin and Ruth Arlow. 2007. ‘Re David Edward Chislett. Tribunal of Enquiry: Diocese of Brisbane.’ Ecclesiatical Law Journal 9, 137–39.

Granville, Paul. 1918. ‘Douglas Price – Tragic Modernist.’ https://highgatehill-historical-vignettes.com/2018/09/09/douglas-price-tragic-modernist/

Hill, Stephen. 2022. ‘A very different Kind of Parish.’ The Catholic Weekly, 13 May, https://www.catholicweekly.com.au/a-very-different-kind-of-parish

Hilliard, David. 1994. ‘The Anglo-Catholic Tradition in Australian Anglicanism.’ http://anglicanhistory.org/essays/hilliard1993.pdf

Hilliard, David. 2010. ‘“Queensland is Catholic as a general rule”: Anglo-Catholicism in Queensland, c. 1860-2010.’ In Marcus Harmes, Lindsay Henderson, and Gillian Colclough (eds), From Augustine to Anglicanism: The Anglican Church in Australia and Beyond. Toowoomba: Anglicans in Australia and Beyond, 103–16.

Kissick, D. L. 1937. All Saints’ Church Brisbane 1862–1937. Brisbane: All Saints Church.

Moses, John. 2011. ‘Peter Bennie at All Saints’, Wickham Terrace, and as Editor of The Australian Church Quarterly, 1952–1963.’ http://anglicanhistory.org/aus/moses_bennie.pdf

Pear, David. 1996. ‘Pulpit Socialist or Empire Wrecker? The Rev. Farnham Edward Maynard of All Saints’, Wickham Terrace.’ Queensland Review 3, 15–23.

Ralston, A. 1920. ‘Douglas Price: A Biographical Sketch.’ In Meredith Atkinson (ed.), The Place of Ethics and Religion in Education. Brisbane: A.J. Cumming, 5–17.

Rayner, Keith. 1963. ‘The History of the Church of England in Queensland.’ PhD thesis, The University of Queensland.

Related articles

![Figure 5: Douglas Price [details needed] (SLQ). Figure 5: Douglas Price [details needed] (SLQ).](https://qareligion.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/5-Douglas-Price-details-needed-SLQ.-.jpg)