Lutheranism in Indooroopilly:

Architecture, art, and music at St Peters Chapel

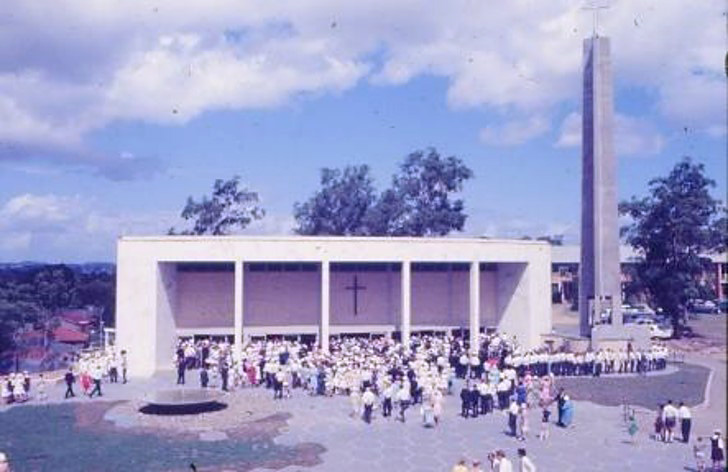

In 1968 St Peters Lutheran College Chapel in Indooroopilly opened, designed by the Vienna-born émigré Dr Karl Langer (1903–69), a highly educated and intellectually inquisitive architect. An exemplar of post-war modern ecclesiastical architecture, the chapel continues to be a place for worship and music, its design contributing to the experiences of its congregations.

By Lisa Marie Daunt

This is a 20 minute read, published in June 2024.

In the 1960s, Australia’s Lutherans embarked on modernising their Church. When the two remaining Synods formally merged into the Lutheran Church of Australia in October 1966, Queensland’s Lutherans were experiencing a time of growth, concurrent with the post-war church building boom stimulated by each of the State’s Christian denominations (Daunt, 2021: 258; Sterken and Daunt, 2021: 402–4). Nonetheless, the enduring attachment to their original roots becomes apparent in the fact that most congregations called on émigré architects from the Germanophone part of Europe to design their new church buildings. Notable interstate examples are Fredrick Romberg and Eric von Schramek, and, in Queensland, Karl Langer (Sterken and Daunt, 2020: 351).

Within Queensland architectural history Langer is one of the most significant architects of the post-war decades. He came to Queensland with an education and portfolio of work far surpassing that of his Queensland peers. Recently, his achievements have gained considerable recognition with the publication of Karl Langer: Modern Architect and Migrant in the Australian Tropics (van der Plaat and Macarthur, 2022), and on his ecclesiastical architecture several pieces have been written by this author (Daunt, 2021; Sterken and Daunt, 2021, 2020).

St Peters College Chapel was one of his last designs to be realised and was purportedly his favourite. Langer’s own words were recorded by a journalist at the opening: ‘A man may strive for excellence for a lifetime, but there will always be one accomplishment which he feels rises above the rest’ (The Sunday Mail, 16 June 1968: 30). Indeed, Langer created for the Lutherans at Indooroopilly one of the finest examples of modern religious architecture in Queensland and beyond (Sterken and Daunt, 2020: 361). For this design he drew on an astonishing breadth of knowledge¾ideas gained from Europe, the United States, and locally (particularly for the sub-tropical climate); highly resolved ideas on modern architecture and art; emergent global changes in liturgical renewal and Christian worship practices; urban, landscape and campus planning; as well as for auditoria design to support speech, singing and musical instruments.

The architect and the chapel’s architecture

Langer was born and educated in Vienna (Austria) — ‘a city immersed in the social, intellectual and artistic practices of design across all its scales’ (Goad et al., 2022: 15). He was trained within one of Vienna’s ‘premier institutions for the training of architects,’ gaining ‘an unusually comprehensive education, one that would leave him uniquely qualified, perhaps overly so’ (Goad et al., 2022: 17). He then worked for one of the Europe’s first-generation modern architects, Peter Behrens, then gained a doctorate in art history, specifically in concrete construction, and had also successfully started his own practice, before the Second World War escalated. He and his Jewish wife then fled, via Athens, Greece — an intentional stop that would later influence the architecture and setting of St Peters Chapel — to Sydney, Australia. They escaped from what had been the cultural hub of Europe.

In stark contrast to Vienna, in the 1930s Australia was being portrayed as Der unvollendete Kontinent (‘the unfinished continent’) in the films and travel writings of Colin Ross (van der Plaat and Macarthur, 2022: 2 and Goad et al., 2022: 40). They arrived in Brisbane July 1939. This shift at the age of thirty-five would have been ‘an intellectual wrench of extraordinary proportion.’ They were both dismayed by Brisbane’s cultural scene, which led them to their ‘shared dedication to help to improve the situation’ Goad et al., 2022: 16). Langer went on to greatly impact the local architectural scene as an architect, landscape architect, town planner, university lecturer, public intellectual, and as one of the first members of the Queensland National Trust (Sinnamon, 2000; Gardiner, 2023: 117). His influential 1944 booklet Sub-Tropical Housing illustrates both his keenness and thoroughness to develop an understanding of his adopted homeland. In his designs, he combined this local knowledge with his European training and cultural and travel experiences — as epitomised in the design of St Peters chapel.

Langer designed at least fourteen churches and chapels, of which about half were realised. Most of these were for the Lutheran church, including St John’s in Bundaberg (1960), St John’s in Ipswich (1961), and St Peters College chapel (1968) in Indooroopilly (Sterken and Daunt, 2020: 353). The reasons for this can only be speculated. One motive may have been his cultural affiliation through his Germanophone background, though he was raised as a Roman Catholic. Another reason was perhaps that the Lutheran congregations saw in Langer’s progressive and modernist take on architecture a way to foster their self-image as a progressive, outward looking faith. For each of these projects he collaboratively engaged with his Lutheran client’s theology (Mayer, 2019). For his part, these ecclesiastical commissions also allowed Langer to experiment with a formal and symbolic architectural register different from the functionalism of most of his other work (Sterken and Daunt, 2020: 353).

St Peters Lutheran College Chapel in Indooroopilly, whilst not opened until 1968, was designed by Langer as part of a masterplan for the school campus, a project he took on from the mid-1940s, not long after the school first opened. While the chapel was one of the last school’s buildings Langer completed, from early it was a centre piece of the masterplan — the spiritual heart of the school. The masterplan illustrates his ability to refer across classical principles and modern architectural form, with a view to producing a dignified yet functional ecclesiastical building imbued with religious symbolism.

The influence of Greek temple complexes and their settings on the design for St Peters and earlier projects has been stressed by Langer himself and described by various Queensland architectural historians (Sinnamon, 1985 and 1988; Hampson and Gardiner, 2017: 219–20). Yet, it was only at St Peters, thanks to the hilly topography, that Langer’s vision of the Greek acropolis was fully realised. The classical inspiration also pertains to the architecture itself. In terms of form, St Peters ‘recalls (but does not replicate) the unequivocal presence and classic calm of a Greek temple’ (Sinnamon, 1985: 55–56). This came to the fore in particular design elements such as the use of a curved plane for the chapel’s front façade and the resulting optical effect; the interior curves of the gallery soffit; and the curve of the ceiling into the sanctuary wall (Sinnamon, 1988: 251). Yet, St Peters arced colonnade, finished white marble slab veneers — an unusual and expensive material — also brings to mind the stripped classicism of Gunnar Asplund’s Woodland Crematorium in Stockholm, Sweden (1935–40).

Figure 2: The front façade and chapel forecourt of St Peters Lutheran College Chapel, 2016 (Lisa Daunt).

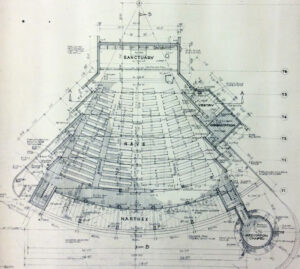

In a similar way, Langer’s departure from the rectilinear church plan offers an illustration of how he absorbed a wide variety of influences into a highly original synthesis. Fan-shaped worship spaces, saw-toothed side walls and sloped floors can indeed also be found in various international cases, as well as a few Queensland examples opened from the late–1950s — a notable example is the Ipswich Central Memorial Congregational church (1958), designed by Scorer and Scorer (Daunt, 2021: 240–44). These deviations were not merely formal, but represented architectural responses to a new understanding of the Christian liturgies and worship practices (formalised by the Catholic Church as part of the Second Vatican Council, 1962–65). Langer initially experimented with these ideas in his 1965 competition entry for the new St Matthew’s Lutheran Church, Maryborough (JOL R83 Folder 19/2; Daunt, 2021: 478 and 484–86). Langer also created a modern version of a classical Greek amphitheatre in selecting the fan-shape and sloping floors — the interior, too, gains from Greek influences (Elgar and Mayer, 2023).

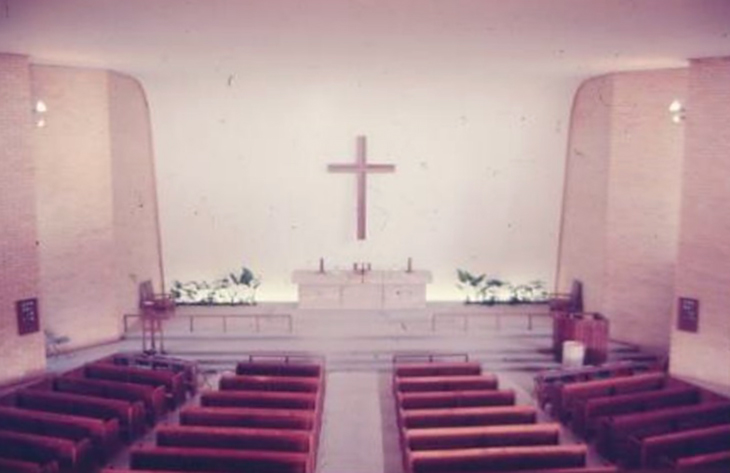

In adopting and developing these emergent ideas, the interior form of Langer’s design directly engaged with Lutheran theology, developing an architecture distinctly different to the tall volumes of Europe’s many Gothic cathedrals and churches, which suggest the people need to look up to the heavens and to reach upwards to gain a relationship with God. As Pastor Reinhard Mayer — the Pastor who collaborated with Langer for the design for St Peters — explained (Mayer, 2019):

God is here amongst us … we can’t reach up to God. We haven’t got the ability. God had to come down to us … that’s where this building demonstrates that so effectively … and then you can see everything slopes where? the altar and the cross.

The design also tells the story of the Resurrection, the name the Indooroopilly Lutheran church congregation would later take (Mayer, 2019):

Now in most Lutheran churches you will find the altar with the crucifix on it, representing we are saved through the cross of Christ. This concept — the resurrection. So, you have the altar like a tomb above it is an empty cross, as Jesus has risen. That is further highlighted by the light coming from the floor behind, representing the dawn of the new day, Easter morning, the new light.

… the resurrection focus — there is no end wall, it is the ceiling, it starts up above us and slopes down and disappears, and behind the wall and in front of that now is the light of the new day. This is symbolic of God reaching down to us through the cross and the resurrection. The central meaning to the Christian faith — the cross and the resurrection.

Pastor Mayer also recalled the clarity and synthesis of the ideas Langer embodied in the chapel’s design:

… everything directs your attention to that focal point at the front. There are no side windows visible, there was to be nothing on the walls to distract your attention. He wanted simplicity, a compelling message and of course harmony … some of that harmony has been destroyed through the fact that the chapel had to be used as a concert venue before the performing arts centre was built [opened in 2013]. In its original concept it [the chapel] was open at the front [the sanctuary] giving full access to God, no barriers to God … that was beautifully pictured with the pulpit near the wall on one side and the lectern on the other, and all in the same timber to balance the whole. Even the carpet was a neutral colour to highlight the altar.

Every seat in the chapel has an uninterrupted view of the altar and to the Pastor. The design gathers the congregation around the sanctuary and the Pastor and, in doing so, imparts a feeling of togetherness and of community — especially when the chapel is at its capacity of 600.

The renewed emphasis on the gathering of the faithful and on the spoken word led to a greater attention to visibility and acoustics. This explains why the typology of the auditorium became a very popular blueprint for church designs. In fact, given the importance of the spoken word and bible reading for Lutherans, visual focus and good acoustics had always been a primary concern for Lutheran churches.

Alvar Aalto’s widely referenced Vuoksenniska Lutheran Church in Imatra (Finland, 1958) immediately comes to mind here — its multi-vaulted ceiling rises towards the narrow north wall, supporting the sound conduction of both voices and organ (Stock, 2002: 233). Similarly, in St Peters, the curved sanctuary wall and the sloped ceiling create an acoustic effect that greatly enhances the intimacy of the liturgical experience and the focus on the altar.

Whether Aalto’s design inspired Langer we can only speculate, but the fact remains that in his early career, Langer also worked as an acoustic design specialist for some of Europe’s famous auditoria, purportedly achieving for several buildings that elusive quality ‘perfect acoustics’ (Sinnamon, 1988, 251). For the Grosse Hörsaal of the Viennese Volksbildungshaus in V. Stöbergasse in Vienna he completed an acoustic and interior refurbishment in 1937 (Goad et al., 2022: 39). He had success with his competition entry of a new Opera House and Conservatorium for Istanbul in 1934 (Goad et al., 2022: 34; UQFL158 Box 42) and entered the Sydney Opera House competition of 1956 (van der Plaat and Macarthur, 2022: 2 and Watson and Gardiner, 2022: 89; UQFL158 Misc. 190226).

While the acoustic performance of the chapel is good, Langer was not entirely happy with the result. He had believed that the acoustics should have been excellent (Mayer, 2019). It is a large space and the Pastor does need to project his voice. To some extent the quality of sound does depend on where you sit — the very best seats are to the centre of the congregation (Elgar and Mayer, 2023). However, the acoustics of St Peters does exceed the performance of most Queensland ecclesiastical buildings, particularly its postwar (1945–77) counterparts. This was achieved in St Peters by Langer’s harmonious combination of form and materials — the curved sanctuary ceiling and wall effectively throws the voice of the Pastor out from the sanctuary and across the congregation. And when the congregation and church choir sing, the building ‘blends the voices’ (Elgar and Mayer, 2023), as further discussed below.

The liturgical furnishings, artwork, and symbolism

It might seem surprising that, in an explanatory note written for his clients ahead of the chapel’s opening, Langer made no mention of his ‘Greek’ inspiration, nor of the architectural and liturgical modernity of his design (UQFL158 Box 17). Indeed, it seems that Langer rarely (if ever) over played his European background or the true breadth of his expertise when communicating with his clients (Sterken and Daunt, 2021: 407; Mayer, 2019). Instead, he deliberately focused on its symbolism and ‘performance’ in terms of worshipping — allegedly of more interest to the congregation than the church’s design influences or architectural novelties. As a result, his explanation, which became part of the opening ceremony handout, largely focussed on the chapel’s internal arrangement, liturgical furnishings, and artwork, as well as hinting at the lack of prominence of or even absence of traditionalist features and decorations within the design.

Figure 4: Chapel interior, photographed by Richard Stringer, c. 1968 (Fryer Library, University of Queensland).

The chapel’s liturgical furnishings were all designed by Langer — the stone altar and timber sanctuary cross, the timber pulpit and lectern, a stone baptismal font, timber candelabra, two timber flower pedestals, timber sanctuary seats for the adjudicating Pastor, the timber congregation pews, as well as timber hymn boards (UQFL158 Job 1050; JOL R38 Job 1050; Mayer, 2019). Whilst the pews, altar, and cross remain today, the others have been replaced with metal and glass movable pieces (arguably lacking the piety and warmth of those they replaced).

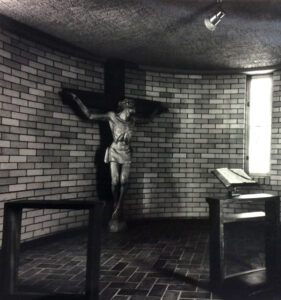

As Langer penned, the fan-shape plan of the chapel and the arrangement of the pews underscore the importance of the altar as the central focus of attention. The same concern to eliminate any distraction, also explains why the lights were hidden from the nave and why the curved wall behind the altar was plain. Also, the use of symbols was restrained to the utmost, but, as Langer noted, ‘each symbol has been brought out to the fullest’ (Langer, 1968). Here, he referred to the contrast between the large and heavy Helidon sandstone altar with the Greek letters ‘Α’ (alpha) and ‘Ω’ (omega) carved into it and the sanctuary cross, which was finished matt (not glossy) and empty. The latter represents both Lutheran piety and Lutheran belief in the resurrection of Christ. Therefore, Langer noted, it is ‘floating in the strong light symbolising the rising sun’ (Langer, 1968). Further, the three fins of the tower which enclose the meditation chapel symbolise the Holy Trinity, a theme which is repeated in the meditation chapel with its three windows (and where the crucifix with Christ’s body is displayed).

Langer’s use of symbols at St Peters was restrained. To understand this, we can look to his earlier designs, particularly St John’s Bundaberg, where he was more exuberant, reincorporating the stained-glass windows of their earlier church and integrating numerous Lutheran symbols into the building fabric (Sterken and Daunt, 2021, 2020).

Besides these symbols and the recently-removed circular water fountain, only one piece of artwork was commissioned, ‘The Corpse’. The commissioned artist, Alfred Schubert, was a European émigré, like Langer, who had arrived in Australia with this wife in 1955 and settled in Melbourne. A Czechoslovakia-born woodcarver trained in Bavaria, Schubert crafted various pieces for modern Victorian Catholic churches (Richardson, 2020, 187; Stevenson, 2010). He made the timber crucifix for the sanctuary of St John’s Lutheran Bundaberg (1960) and another for the meditation chapel of St Peters Lutheran College Chapel. Both these pieces are figurative, realistic portrayals of a suffering Christ. Both pieces were also the result of Langer collaborating with Schubert (UQFL158 Box 17).

At St Peters, ‘The Corpse’ is positioned within the mediation chapel for most of the year. It is only positioned within the worship space proper for a short period of the liturgical Calendar — during the Lenten Season leading up to Good Friday a procession of students carries it in, hangs it on the wall to the side of the lectern, and then carries it out again at Easter. Being a church of ‘the Resurrection’, the suffering Christ is not the focus, instead the focus is on the empty cross and the resurrected Christ (Mayer, 2019).

The music of St Peters Resurrection Church

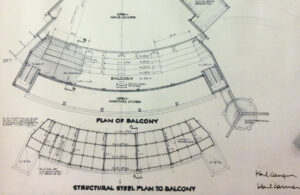

In response to the school council’s brief, Langer had master planned a greater role for music St Peters than was built. Langer’s surviving archives give insight into what might have been had more funding been gained. A June 1962 master plan depicted a rectilinear scheme and gave the building a dual label — ‘Proposed Chapel for 600, Music Centre Underneath’. By August 1962, further master planning showed the fan-shaped planning and tower, very similar to the chapel floor plan that was built. Showing further detail than the master plans, the 27 August 1966 working drawings for the Chapel included a music room with a terrace under the sanctuary end of the building (UQFL158 Job 1050; JOL R38 Job 1050).

The project was tendered in February 1967. However, after lengthy deliberations Langer redocumented it, with the music room and terrace absent from the 14 April 1967 construction drawing set (UQFL158 Box 43; JOL R38 Job 1050). The music room instead took the place of the former school chapel on the upper floor of the recently demolished Luther House (erected in 1948). The architectural design of the chapel itself survived budgetary deliberations unaffected, with the worship space’s musical qualities intact.

The experience of music — the singing of liturgy and hymns and organ music — has to date received limited attention within the architectural historiography for modern ecclesiastical architecture. Langer’s love of music was recognised through his 1968 appointment to the Australian Council for the Arts and election as vice-chairman of its music board (Sinnamon, 2000). Music was and is integral to Lutheran worship and has remained so at St Peters chapel.

The prominence of music in Lutheran worship can be traced back to just after the reformation, when Martin Luther founded the faith:

The chief musical reform of the Lutheran church in the sixteenth century was the establishment of congregational singing as a vital ingredient in corporate worship … The uniqueness of Lutheran hymnody lies in the fact that from the very beginning it has been an important part of the liturgy, not — as in most other traditions — a general Christian song loosely attached to worship … For worshipping Lutherans, congregational song centres in the singing of hymns of proclamation and praise, prayer and adoration (Schalk, 1978: 6–7).

In Lutheran Churches, congregational participation and singing continued through to the post-war decades and into the present. In contrast, the global Roman Catholic Church (and the Anglo-Catholic Church of England/Anglican Church) had over the centuries shifted away from the participation of the congregation in the liturgy (Daunt, 2016: 226). It was not until the turn of the twentieth century, concurrent with the early beginnings of the liturgical movement, that Catholic Churches abroad started to reintroduce Gregorian Chant and subsequently ‘dialogue’ Mass (Proctor, 2014: 140–41).

In the 1960s Queensland Lutheran Pastors sung the liturgy in dialogue with their singing congregation. As Pastor Mayer recalled, singing was an expected part of a Pastor’s training and part of congregation’s worship practices (Mayer, 2019). Thus, in the 1960s (and the decades following) worship was experienced in a remarkably similar way to the Gregorian Chant of Renaissance times, sixteenth century (Elgar and Mayer, 2023). Over half of the services today at St Peters Resurrection Church are sung liturgies, in a mix of contemporary and more traditional songs. Once a month a ‘traditional’ sung liturgy is used. Only once a month the liturgy is spoken.

The Pastor’s voice can be heard by all congregation members, singing or speaking. Whether he is standing at the altar (behind or in front), the pulpit, or the lectern, the curve of the sanctuary wall throws the sound out. As Langer himself explained, the altar and cross are the focal point of the design for the congregation, the acoustics favouring the altar (Elgar and Mayer, 2023).

In Langer’s design, the choir and the organ (initially an electric organ but upgraded to a pipe organ from 1976–83 (Cox, 2012) were both positioned to support the congregation. Thus, the choir are not performers, and the congregation are not spectators — as per Lutheran theology. The church choir sits or stands within the gallery, as does the organ, which was placed at the centre back of the same gallery space (the organist moved forward when the organ was upgraded, with the pipes taking the centre back position). The congregation are participants, singing with the choir as active participants. Indeed, the positioning of the church choir and organ at St Peters has been recognised as the most fitting for Lutheran worship — and perhaps even as the best acoustic set-up — by several American Lutheran authors (Caroll, 1999: 95–96).

Figure 9: The gallery of St Peters College Chapel, with the seating now divided by the organ position and organ pipework, 2016 (Lisa Daunt).

Langer’s careful selection of timber, plaster, brickwork, and carpet (recently replaced with a plusher carpet, reducing the reverberation) — achieved a reverberation and quality of sound that ‘blends the voices … the sound blooms’ (Elgar and Mayer, 2023). The building sings with its worship community, the sound travelling out into the forecourt through open doors, extending the musical space and drawing anyone outside towards the music within (Elgar and Mayer, 2023).

The skills of the organist, choir conductor, and choir members are highly valued at St Peters. The current organist, Gregory Mayer (Pastor Mayer’s youngest son), has been the professional organist for more than thirty years for various churches, and was the organist at Brisbane’s St Stephen’s Catholic Cathedral for seven and half years. The current choir conductor, Tricia Elgar, is a formally trained singer and a highly regarded soloist and music educator. Various members of the choir are also talented musicians, with choral bursaries regularly given to attract new talent (Elgar and Mayer, 2023). Pastor Mayer, now retired from pastoral duties, still sings with the choir as a tenor.

The choir’s broad musical repertoire reflects various genres and languages. Recently the choir has sung Pie Jesu, as composed by Andrew Lloyd Webber, with two soprano soloists; Baba Yetu in Swahili; Maurice Duruflé’s Ubi Caritas in Latin; J.S. Bach’s Cantata No. 61 in German; and Josef Gabriel Rheinbergen’s Abendlied also in German. If the Langers arrived in 1939 to a city that lacked culture, the chapel Langer designed has contributed to improving the situation, and today it is both a place where Lutheran worship and culture entwine with engaging musicality.

Conclusion

The architecture of St Peters Lutheran College Chapel demonstrates the astonishing breadth of Langer’s expertise. He seized the opportunity to explore the urban, architectural, and symbolical potential of ecclesiastical architecture. His intellectual rigor allowed him to adapt seemingly effortlessly multifarious influences to the economic and climatic constraints of post-war Queensland (Sterken and Daunt, 2020).

However, the value of Langer’s design for the St Peters chapel extends well beyond its contribution of modern architecture in Queensland — a contribution recognised in 2015 with an enduring architecture award from the Queensland Chapter of the Australian Institute of Architects (Watson and Gardiner, 2019: 33) and listing in 2012 on the Queensland State Heritage Register. For more than fifty years it has been a highly regarded place for Lutheran worship, where the community embraces congregational singing, enriched by both the talents of the church choir and musical calibre of a professional organist. First opened and dedicated on 14 June 1968, the school and church community is now embarking on much needed heritage repairs and conservation works to extend the chapel’s use for many more years.

Acknowledgements

This QAR entry further develops and extends research previously published by the author with Sven Sterken. These previous publications are referenced within the text and bibliography, as too are more recent publications by others.

Archival sources

John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

JOL R38 Job 1050. Karl Langer Architectural Plans, St Peter’s drawings, and Matthew’s competition drawings (Folder 19/2).

Fryer Library, University of Queensland

UQFL158 Box 17. ‘St. Peter’s Lutheran College — Chapel Symbolic Values.’ January 25, 1968.

UQFL158 Box 42. Istanbul project.

UQFL158 Box 43. Dedication booklet.

UQFL158 Box 44. Karl Langer Collection.

UQFL158 Box 75 (Folder 201). Karl Langer Collection.

UQFL158 Job 1050. Karl Langer Collection (1947–1968).

UQFL158 Misc. 190226. Sydney Opera House competition entry.

Sources and further reading

Carroll, Roy William. 1999. ‘Place, Praise and Faith: a study of architecture and music in the Worship Life of the Lutheran Church.’ PhD thesis (unpublished), The University of Iowa.

Cox, Gregory. 2012 (updated March 2019). ‘St Peters Lutheran College.’ https://www.ohta.org.au/organs/organs/IndooroopillyStPetersCollege.html, accessed April 14, 2023.

Daunt, Lisa Marie. 2016. ‘1960s Brisbane Church Architecture: Creating modern, climatic and regional responses to liturgical change.’ Queensland Review (Special Issue, Queensland Modernism) 23, 2: 224–45.

Daunt, Lisa Marie. 2021. ‘Communities of faith: Modern church architecture in Queensland, 1945–1977.’ PhD thesis (unpublished), The University of Queensland.

Elgar, Trica and Gregory Mayer. 2023. Interviewed by Lisa Daunt (June 3, 2023), unpublished.

Gardiner, Fiona. 2023. ‘Modernist and Heritage Conservationist: Karl Langer’s Contribution to the Heritage Movement in Queensland.’ In Julia Gatley and Elizabeth Aitken Rose (eds), Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand: 39, Ngā Pūtahitanga / Crossings. Auckland: SAHANZ, 117–31.

Goad, Philip, Andrew McNamara, and Andrew Wilson. 2022. ‘Vienna: Karl and Gertrude.’ In van der Plaat, Deborah and John Macarthur (eds), Karl Langer: Modern Architect and Migrant in the Australian Tropics. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 14–47.

Goad, Phillip, Ann Stephen, Andrew McNamara, Harriet Edquist and Isabel Wünsche. 2019. Bauhaus Diaspora and beyond: Transforming Education through Art, Design and Architecture. Carlton (VIC): Miegunyah Press, 2019).

Hampson, Alice and Fiona Gardiner. 2017. ‘From the Acropolis to Kingaroy: Creating Civic Culture in Queensland.’ In Gevork Hartoonian and John Ting (eds), Quotation, Quotation: What Does History Have in Store for Architecture Today? Canberra: SAHANZ, 215–25.

Langer, Karl. 1944. Sub-tropical housing. Brisbane: University of Queensland.

Macarthur, John, Deborah van der Plaat, Janina Gosseye, and Andrew Wilson (eds). 2015. Hot Modernism: Queensland Architecture 1945–1975. London: Artifice Books on Architecture.

Mayer, Reinhard. 2019. Interviewed by Lisa Daunt (July 6, 2019), unpublished.

Neale, Doug. 2012. ‘Langer, Karl.’ In Philip Goad and Julie Willis (eds), The Encyclopaedia of Australian Architecture. New York: Cambridge University Press, 400–1

Proctor, Robert. 2014. Building the Modern Church: Roman Catholic Church Architecture in Britain, 1955 to 1975. Farnham: Ashgate.

Richardson, Elizabeth. 2020. ‘The untold story of modernism: a critical analysis of the post-war church in Victoria, Australia, 1950–1970.’ PhD thesis, University of Melbourne.

Schalk, Carl F. 1978. Music in Lutheran Worship. St Louis: Concordia Publishing House.

Sinnamon, Ian. 2000. ‘Langer, Karl (1903–1969).’ Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/langer-karl-10783/text19123. Published first in hardcopy 2000, accessed online July 4, 2016.

Sinnamon, Ian. 1988. ‘Landscape with Classical Figures — a German influence On Queensland Architecture.’ In Manfred Jurgensen and Alan Corkhill (eds), The German Presence in Queensland Over The Last 150 Years. Proceedings of an International symposium. August 24, 25 and 26, 1987, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia. St Lucia: Department of German, University of Queensland.

Sinnamon, Ian. 1985. ‘An Educated Eye: Karl Langer in Australia.’ Landscape Australia, 1/85 February: 48–56

Sterken, Sven and Lisa Marie Daunt. 2021. ‘Tempered Modernism: Karl Langer’s Architecture for the Lutheran Church in Queensland.’ Fabrications 31.3: 398–426.

Sterken, Sven and Lisa Marie Daunt. 2020. ‘From Austria to Australia: Three Lutheran Churches by Karl Langer.’ In Victoria Jackson Wyatt, Andrew Leach and Lee Stickells (eds), Distance Looks Back: the 36th Annual Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand. (Sydney: SAHANZ, University of Sydney, 350–61. https://www.sahanz.net/wp-content/uploads/SAHANZ_19_Sterken_Daunt.pdf

Stevenson, Michelle. 2010. ‘Eva Schubert, German Migrant & Artist, 1955.’ https://collections.museumsvictoria.com.au/articles/3530. Accessed 20 May 2023.

Stock, Wolfgang Jean (ed.). 2002. European Church Architecture 1950–2000. Munich: Prestel.

Thiele, Otto. One Hundred Years of the Lutheran Church in Queensland. Brisbane: Publication Committee of the Queensland District United Evangelical Lutheran Church in Australia, 1938.

van der Plaat, Deborah and John Macarthur (eds). 2022. Karl Langer: Modern Architect and Migrant in the Australian Tropics. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Watson, Donald and Fiona Gardiner. 2019. ‘Archive of an Architect: The Karl Langer Collection.’ Fryer Folios 12, 1: 32–39.

Watson, Donald and Fiona Gardiner. 2022. ‘Bend Like a Bamboo: Always Bounce Back,” in van der Plaat, Deborah and John Macarthur (eds), Karl Langer: Modern Architect and Migrant in the Australian Tropics. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 74–103.

Related articles