Swedenborg to Soul Warrior: The Brisbane Society of the New Church

The Brisbane followers of Swedish mystic Emanuel Swedenborg have been a small but enduring presence in the city's religious landscape. From their origins in the 1860s to the present, Brisbane's Swedenborgians have pursued an evolving vision of Christian life.

By Bill Metcalf

This is a 25 minute read, published June 2024.

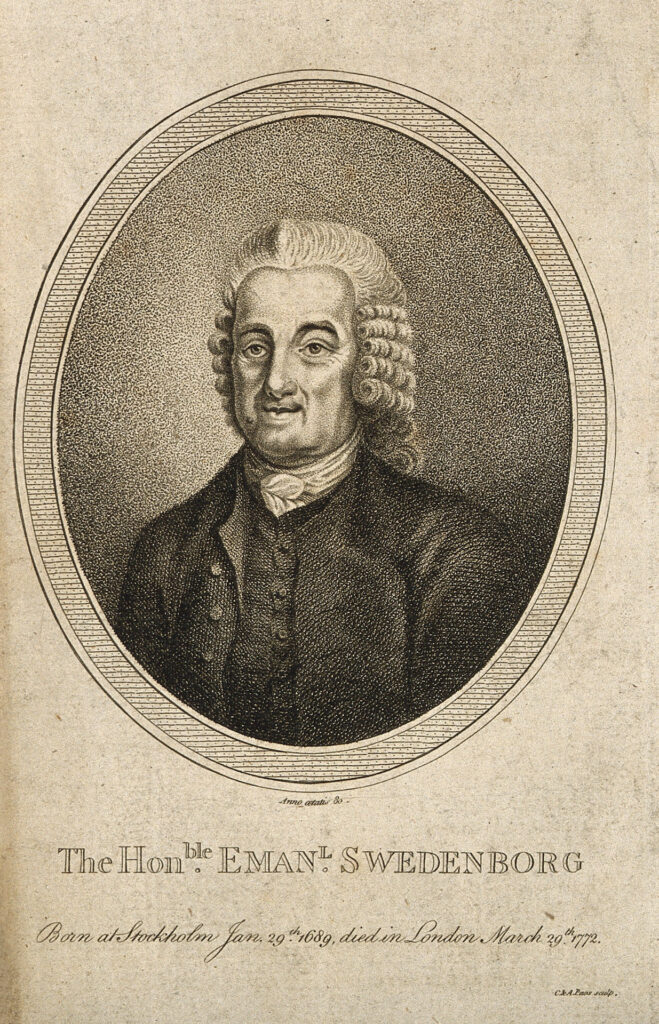

Born into a prosperous Stockholm family in 1688, Emanuel Swedenborg is celebrated as a learned figure in the Swedish society of his day, a scientist, philosopher and theologian. He travelled widely, studying natural sciences, and published prolifically. In later life Swedenborg became increasingly inclined to mystical and spiritualist reflections, and devoted his attention to biblical and other, more obscure, religious writings.

His introspective mysticism led him to seek a new church ‘related to the New Jerusalem mentioned in the book of Revelation’. Swedenborg experienced numerous esoteric dreams and out-of-body experiences, including visions of Christ, even while awake, and these he believed to be divine messages. He claimed to have ‘travelled in heaven and hell and witnessed in detail the actual state of people after death’ (Synnestveldt, 1970: 25–6; Suzuki, 1996: 5). He also claimed to have had (Sharp, 1989: 1–16):

direct and intimate intercourse with the spiritual world, and to hold converse with spirits and angels, whose sayings, surroundings, and doings are recorded in a score or more many paged volumes. … I have been called to a holy office by the Lord Himself, who most mercifully appeared before me, His servant … when He opened my sight into the spiritual world.

These profoundly mystical insights led Swedenborg to interpret the Bible with regard ‘to what he had seen and heard in the world of spirits and angels.’

Swedenborg’s teachings and followers

God, he claimed, manifests himself in many forms but ‘mankind has removed itself so far from its origin that the Lord allowed himself to be born into the human worlds through a mortal woman’ as Jesus Christ. Swedenborg ‘rejected the doctrine of Christ as the Son of God, as well as the doctrine of the Trinity’. He believed that evil came into and persists in our world, through ignoring or misrepresenting the fundamental spiritual truths which had been revealed only to him (Synnestveldt, 1970: 89–96; Jonsson, 1978: 856; Dingwall, 1962: 11–68).

Soon after his death in 1772, several Swedenborgian Societies were formed in UK, and over time these became known as the Church of the New Jerusalem, or, more commonly, simply the New Church. The first New Church was established in London in 1788 and was soon replicated across England. A General Conference of the New Church was formed in 1789, and it continues to promote, co-ordinate and maintain their theology. In time, this movement spread to the Australian colonies, including to Queensland in the 1860s.

Occasionally, this religious tradition has been called ‘Swedenborgian’, but the label is controversial because it might imply worshiping Swedenborg rather than reading his words to help understand the bible’s deeper scriptural meaning (Synnestveldt, 1970: 35; Brisbane Courier, 25 April 1873: 3, and 10 June 1874: 2).

In Britain’s Australian colonies, the first New Church was established in July 1844 by Jacob Pitman in his Adelaide home. Born in 1810 in Trowbridge, Wiltshire, Pitman trained and worked as a carpenter, and became a Baptist Sunday School teacher. He was receptive to Swedenborg’s writings, and committed himself to promoting these religious insights. Pitman and his wife, Emma, had sailed to Adelaide on the Trusty, arriving in May 1838, where he became a builder and property speculator, but he was bankrupted in 1843. His brother, Isaac Pitman (1813–1897), is famous for having invented what came to be known as Pitman Shorthand (Muirden, 2022).

Jacob Pitman’s small religious group, meeting at his Adelaide home, had only one liturgy and one hymn book to share. In March 1847, they established an informal society, and those present signed the Declaration of Faith which the New Church had adopted in England. In 1848, they moved services from Pitman’s house into rental facilities, then Pitman built their own church, on Carrington Street, Adelaide, in 1850. They incorporated their society in 1888, shortly before Pitman’s death in 1890 (Robinson, 1980: 12–20).

From this modest start in Adelaide, New Churches were established in Melbourne (1853), Brisbane (1865), Sydney (1874), and Perth (1903). In 1881, Reverend John Thornton established the Australian Conference of The New Church to promote and standardise their liturgy and teachings across Australia, a gathering that continues today (Robinson, 1980: 166–8).

The New Church in Queensland

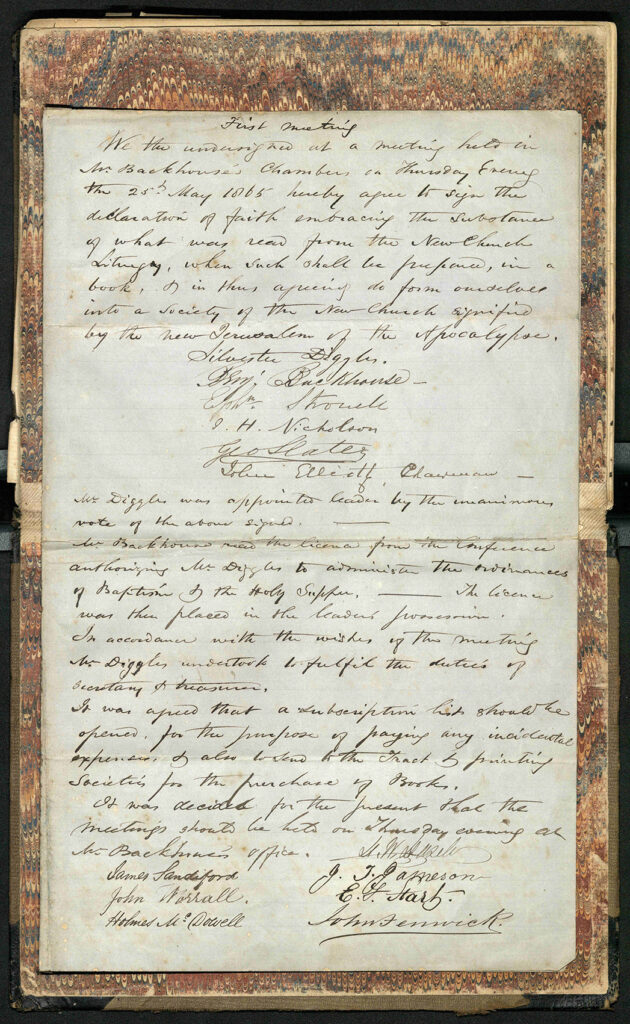

On 25 May 1865, Benjamin Backhouse (architect), Sylvester Diggles (musician and scientist), John Elliot (director of the Brisbane School of Arts), John Nicholson (teacher and writer), George Slater (bookseller) and Ephraim Stronell (businessman) met at Backhouse’s office in Queen Street, Brisbane, to sign a Declaration of Faith. ‘We the undersigned … hereby agree to sign the declaration of faith embracing the substance of what was read from the New Church Liturgy, when such shall be prepared, in a book, and in thus agreeing to form ourselves into a Society of the New Church signified by the New Jerusalem of the Apocalypse.’

Most of these men had previous connections to the New Church in England or Adelaide. They were soon joined by John Fenwick, Edward Hart, John Jameson, Holmes McDowell, James Sandiford and John Worrall. As a group, their Declaration of Faith was:

That God is one, in whom is a Divine Trinity; and that He is the Lord God and Saviour Jesus Christ.

That a saving faith is to believe in Him.

That evil actions ought not be done because they are of the devil and from the devil.

That good actions ought to be done because they are of God and from God.

And that a man should do them of himself; nevertheless, under this belief that they are from the Lord, operating with Him and by Him (New Church of Jerusalem, Brisbane Society, 27 April 1877).

Sylvester Diggles, the only founder to have been ‘certified’ by the New Church in England, became their formal leader. He later explained why Swedenborg’s influence moved him to support the New Church: ‘This time is a very serious one. Science and Dogmatic Theology are at open war and nothing but our system can possibly reconcile modern deducing in Science with ordinary systems of belief’ (Fisher, 2000: 284). The members first met in their homes, then in a suitable room in the Town Hall that was described as ‘a handsome and airy room free of expense’, where their first service open to the public was held on 11 March 1866.

The New Church advertised for more members, offering free lectures to that end, with some success. On 10 March 1873 they held a widely advertised and well-attended public meeting, attracting more members. This influx financed a harmonium, more hymn books, and a free lending library of Swedenborg’s writings. Attendances averaged about twenty for morning and forty for evening services.

Some local ministers warned their parishioners against having anything to do with such a ‘dangerous’ religious group, leading to a witty letter to the Brisbane Telegraph published on 5 February 1873:

On Sunday last, I heard a celebrated divine in Wharf Street advise his hearers not to go and hear about the doctrines of the New Jerusalem Church at the Town Hall. This immediately excited my curiosity, and in the evening I went. The service was conducted by two respectable citizens of unpretending manners, great simplicity, and devotion. There was nothing in the singing, or prayers, or sermon that could offend in any way, and perhaps the best part of the service was its freedom from that priestly and dogmatic arrogance so rampant in the pulpits of our city at the present time. No smell of fire or brimstone after the service was over.

‘The only allusions that I heard to the other sects’, the letter writer continued, ‘was that the persons the most opposed to them were those that least understood their views and doctrines.’

Over a hundred people attended their annual general meeting in 1874, and were told ‘each service comprises Prayers and Thanksgiving from the New Church Liturgy, Hymns from the New Church Hymn Book, the reading of the Word, and a sermon or lecture read from some approved New Church publication. The subject of each sermon or lecture is previously advertised in the daily papers’ (New Church of Jerusalem, Brisbane Society, 23 April 1874).

In 1875 Sylvester Diggles resigned as leader, and John Garsden, later to become Mayor of South Brisbane, took over. Increased attendance led them to rent space in the Temperance Hall on the corner of Edward and Ann streets, and seek land on which to build their own church.

In September 1876 the name ‘New Jerusalem Church’ was formally adopted, but at their 1877 General Meeting, attended by forty-five members, Garsden admitted that all was not happy within the congregation. ‘It is questionable whether the Society is in as good a position or so invigorated as it was a year ago,’ he told the meeting (New Church of Jerusalem, Brisbane Society, 27 April 1877),

Our deficiency seems to be unity. We ought, as a New Church Society, to be more closely bound together by brotherly love, and each member ought to work as though the success of the Church depended upon his own exertions, not only to work while he sees good results, but to do his duty activated by love to the Lord and his neighbour, and if he sees no fruit outwardly, he is in himself rewarded by the good being imparted to him which he wished others to obtain.

At the April 1878 General Meeting, their secretary, James Sandiford, pointed out that ‘there had been no apparent progress during the past year… there are fewer members … than we had a year ago, and there is also a diminished attendance at the services, and there seems to be a want of zeal amongst the members.’

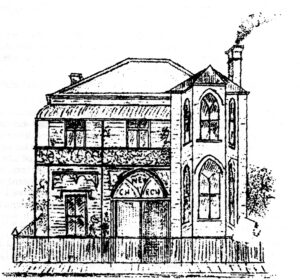

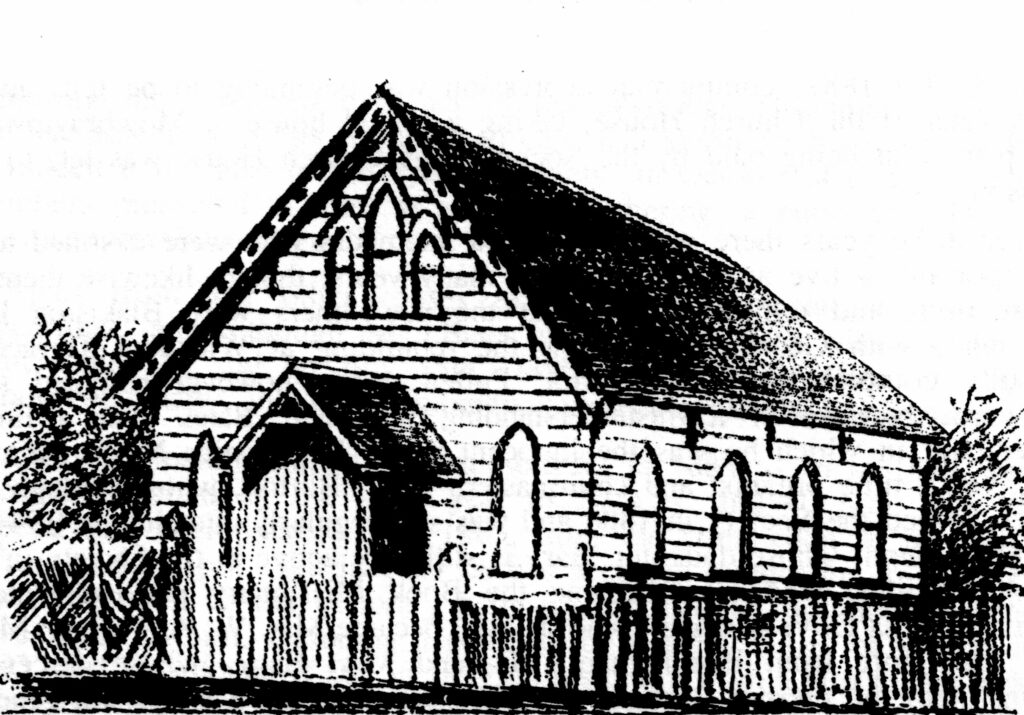

Despite these challenges, Brisbane’s New Church was incorporated in 1878, the legal work done by one of their distinguished members, Mr Justice Mein of the Supreme Court. They located suitable land on Wickham Terrace, opposite All Saints Church, paying £350, then built a timber church costing £460 – all borrowed from members and from a building society with members as guarantors. For unknown reasons, they opened the church ‘quietly and making no public demonstration of any kind.’ All they lacked was a minister (New Church of Jerusalem, Brisbane Society, 23 April, 22 July, 12 August, 6 & 10 October, and 4 December 1878).

Figure 4: Brisbane New Church of Jerusalem, Wickham Terrace, c. 1878 (Robinson, 'A History of the New Church', p. 83).

By the early 1880s, the church was facing other headwinds. It was admitted at the 1880 meeting ‘that many members have been unhappily led away by the delusion of spiritualism.’ Without a permanent minister, members needed ‘the time and ability … to counter effectively the cult of spiritualism, which in 1880 was making inroads into the membership’ (Robinson, 1980: 80). They advertised for a minister in Australia, England, and the United States but no applicant was willing to come for the meagre £100 stipend on offer. Through public meetings, they sought to increase their membership and income, but without success (Brisbane Courier, 9 January 1880: 2; 13 July 1881: 2–5; and 2 and 5 October 1881: 3; Telegraph, 14 July 1881: 2, and 25 May 1887: 3). Members such as James Sanderson were keenly disappointed by the meagre progress. At their November 1882 meeting, Sanderson admitted that when he joined the New Church he was ‘full of hope and firmly believing that the masses were thirsting for the truths I had so newly found. I have lived to learn that this is not so’ (New Church of Jerusalem, Brisbane Society, 21 November 1882).

W. Alfred Bates, although not yet ordained, applied from England to be their minister. The Brisbane members, worrying that they might never find a minister, offered him the post with a salary of £150 p.a., and sent him £80 in advance to cover debts and pay for passage to Australia. Bates arrived in Brisbane with wife and family in November 1882. Despite not being ordained, he was called ‘reverend’ by the Brisbane membership, 120 of whom attended his welcome service on 21 November in a promising start to his tenure. The New Church now had a building, with meeting room and Sunday School below, and a full-time minister – but also a massive debt and limited income. This problem was exacerbated when they borrowed even more money to buy a manse on Union Street, Spring Hill (Robinson, 1980: 80–3).

Reverend Bates suffered from some unknown medical conditions and was often incapacitated. That said, he was a very popular and highly respected leader who worked as hard as his frail health allowed. One parishioner recalled, ‘to be introduced to him was to know him and love him. He had all the qualities of a great and gifted preacher.’ Reverend Bates established a Sunday School, and church membership grew, albeit slowly and erratically. He also had something of an other-worldly, utopian bent, in evidence when he told parishioners in November 1882, ‘I want to lead you to that Golden City the New Jerusalem’ (Robinson, 1980: 82; New Church of Jerusalem, Brisbane Society, 21 November 1882).

In October 1883 Bates convinced members to re-name themselves the Brisbane Society of the New Jerusalem Church, with their objectives stated as (New Church of Jerusalem, Brisbane Society, 23 October 1883):

the worship of the Lord Jesus Christ in the Divine Humanity as the only God, and the promotion and extension of His Kingdom among men by the inculcation and practise of the three essentials of all true religion, namely Love to the Lord, Charity to the Neighbour and a life according to the ten commandments.

In 1884, they sold their Wickham Terrace land for £1250, bought the adjoining block for £650, and moved their timber church to the rear of this block. They then built a manse, Sunday school and library at the front. They now had more debt but less income. When the new railway tunnel to link Roma Street and Fortitude Valley Stations was dug under their church, members sought £250 compensation but only received £7/7/- (Robinson, 1980: 82).

Nevertheless, finally having their own minister, church, and manse, membership grew, albeit slowly. They somehow managed to cover their debts, and their public image shifted to become almost mainstream. Like many churches, they faced intermittent but persistent internal friction based on personality and liturgical clashes. Reverend Bates, who had by this time been ordained by Reverend John Thornton, of Sydney, several times sought to resign but was convinced to remain, even as his health deteriorated. All indications are that he was as good a minister as they could have hoped for, charming, sincere, and diplomatic (Brisbane Courier, 2 June 1885: 4).

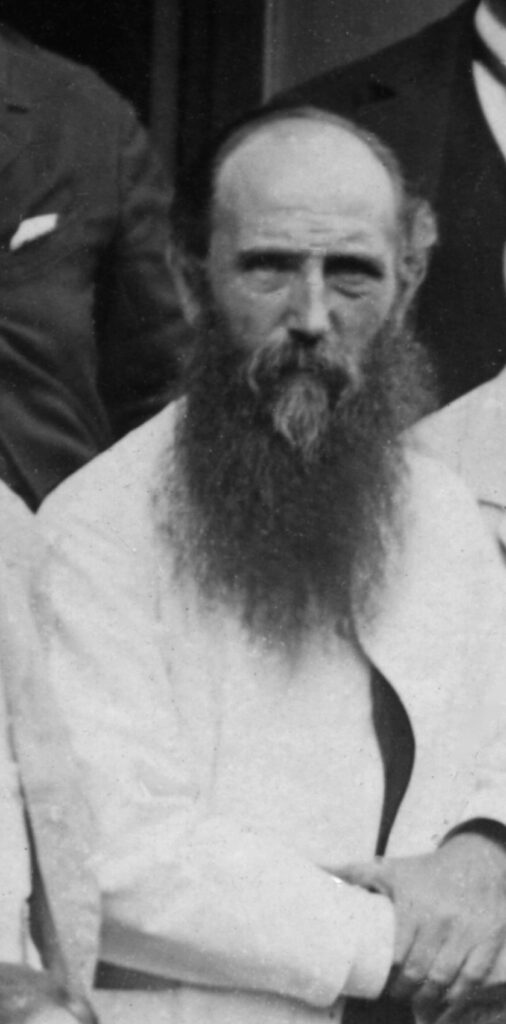

One of their new and very enthusiastic members, having joined in April 1883, was George Chale Watson, a surveyor, utopian-socialist, and advocate of self-sufficient rural communes. Watson owned a large block of land at Rocky Water Holes (Rocklea) on which he had built his considerable house. Then in 1886 he also built his own church next to the house, capable of seating 120 worshippers. This was called ‘Moorooka Mission Hall’, or alternatively the ‘Rocklea Mission Hall.’ Watson was energetic and evangelical, opening a Sunday school, and prevailing on Reverend Bates to occasionally preach there. It appears that Reverend Bates and family may even have lived for a while with Watson (Telegraph, 20 January 1891: 2; Brisbane Courier, 28 January 1891: 6).

Watson offered his church to the New Church for free as long as they would conduct services there. Watson also sought to attract New Church members to join his utopian, self-sufficient, Yeerongpilly Village Settlement scheme, intended to have about two hundred members with its own tram line to Brisbane (Brisbane Courier, 28 January 1891: 6; 14 May 1891: 4-5).

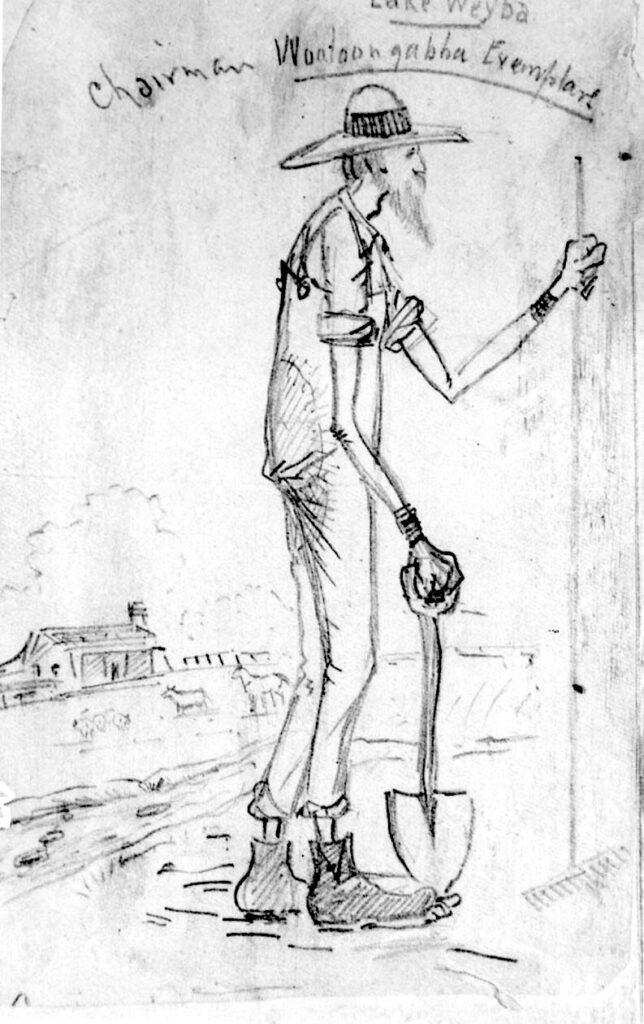

Watson’s utopian scheme was supported, at least in principle, by several prominent Queenslanders including Chief Justice Charles Lilley, the German Consul Heinrich Ruthning, and Premier Samuel Griffith but not, alas, by many New Church members other than Reverend Bates. Serving as deacon in the New Church, Watson was frequently in conflict with other members because of his persistent enthusiasm for a more evangelical, socialist approach. Frustrated with the lack of support from his fellow parishioners, Watson resigned several times before re-joining the New Church, until late 1893 when he formed ‘Woolloongabba Exemplars’ commune on Lake Weyba, near Noosa, with 237 members (Robinson, 1980: 82–4; Metcalf, Kerr and Christie, 2011: 319–35).

As the 1890s economic depression set in, the New Church was no longer able to pay Reverend Bates’ modest stipend. He agreed to continue in a voluntary capacity and work elsewhere to feed and house his family. Nevertheless, during 1890–91 Bates preached nearly one hundred sermons, conducted numerous marriages and funerals, edited their newsletter, taught doctrinal classes, and helped with Sunday School. In spite of serious health problems and declining membership, he held the church together through these tough times. At their April 1894 meeting, members rejoiced that the New Church had survived, ‘notwithstanding the terrible depression that has existed amongst all classes of the community, consequent of the general stagnation of business, the severe floods by which we were visited early in last year, and the utter collapse of most of our great financial institutions that followed.’ They also made the progressive decision that their General Committee henceforth would consist of ‘three ladies and three gentlemen’ (New Church of Jerusalem, Brisbane Society, 22 April 1891, and 13 April 1894).

By 1898 members were more optimistic, recognising (New Church of Jerusalem, Brisbane Society, 29 April 1898):

the great work the Lord is affecting in the world at large, to prepare it and make it a fit abode for his New Church, where in His Wisdom He sees fit to withdraw Her from the obscurity and isolation, and they therefore feel strengthened and encouraged to go quietly on in the path of duty and keep the spiritual centres of activity open so that new life may flow into the world.

Alongside various egalitarian and progressive causes the New Church also evoked the imperial enthusiasm and colonial nationalism of the period. In January 1900, when a young member, William Sabine, set off to fight in the Anglo-Boer War, New Church members expressed their appreciation of his ‘patriotism and sincerely hope that his efforts to support the Empire under its present trying circumstances may be crowned with success’ (New Church of Jerusalem, Brisbane Society, 29 April 1900). Fortunately William Sabine returned, alive.

The Marchant years

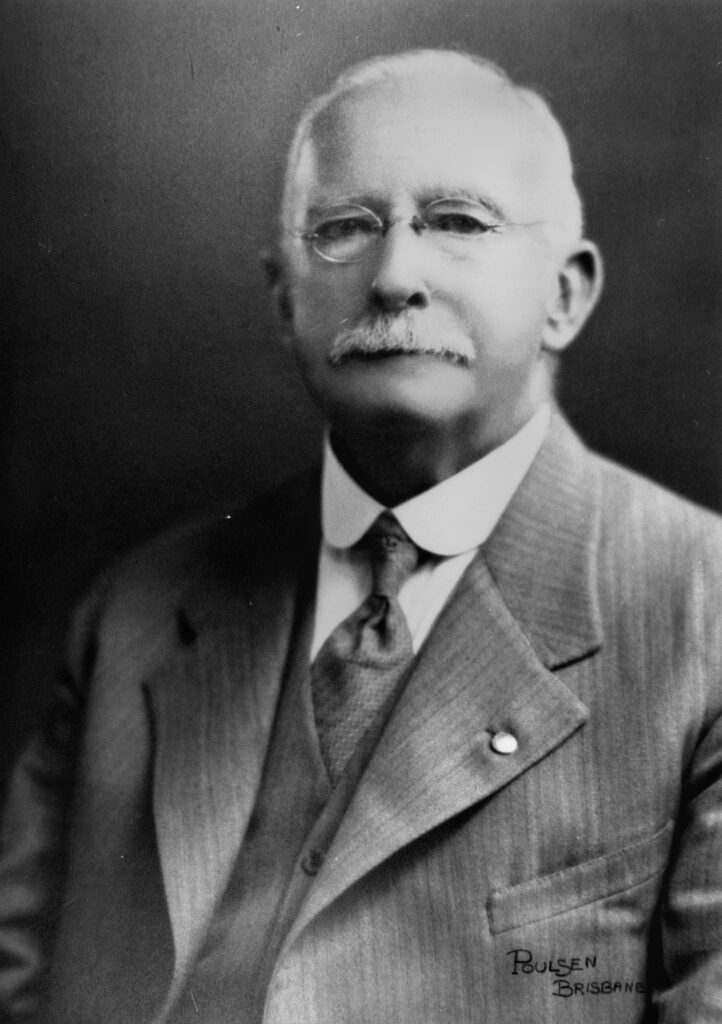

Another new, and less controversial, member at this critical time was George Marchant, a wealthy local businessman. Born in England in 1857, Marchant came to Queensland in 1874. He worked for a soft drink manufacturer, and after buying the business established his own factory in Spring Hill in 1886.

While still a member of the Baptist Church, Marchant had experienced several ‘spiritualist visions’ that convinced him that he was meant to be a preacher and promote the work of God. Perhaps seeking a more acceptable outlet for his spiritual energy, Marchant left the Baptists and joined the New Church in July 1882, and soon became a key supporter and, eventually, minister.

He donated considerable money to upgrade the New Church property and paid half of Reverend Bates’ stipend. Without formal training but with plenty of enthusiasm, Marchant often took over preaching and, in many ways, mostly positive, he was a strong supporter until his death in 1941. Without Marchant’s generous financial support, Brisbane’s New Church might well not have survived.

At their April 1904 annual meeting, members agreed to delete the word ‘Jerusalem’ from the name of the Society, but, oddly, it remained in relation to their church. Another innovation was proposed a year later, as an issue arose that would dog the New Church for decades. Some parishioners sought formal acknowledgment that Swedenborg’s theological works were ‘Divine Truths and the Word of the Lord Jesus Christ to the rational mind of man, and that … [the New Church] acknowledges the coming of these teachings to be a coming of the Lord’ (New Church of Jerusalem, Brisbane Society, 25 January 1905). As this suggested Swedenborg was divine, his words being the ‘Word of God’, the Committee rejected this push. The issue, however, would not die.

In 1908 Marchant offered the New Church a more central block of land, at 345 Ann Street. They sold their Wickham Terrace land and church to Thomas Bain, and built a more substantial brick church on this new land at a cost of £2,200. On 10 February 1909, Reverend Bates laid the foundation stone for this complex, to include church, vestry, and hall before returning to England where he died in 1932 (Telegraph, 22 February 1909: 8; Brisbane Courier, 22 February 1909: 7, and 7 July 1932: 10).

Figure 9: Brisbane New Church of Jerusalem, Ann Street, c. 1930 (Robinson, 'A History of the New Church', p. 87).

In 1910, Marchant generously paid off the New Church’s large mortgage on this comparatively grand building, panelled in silky oak and cedar with electric lights. The particular emphasis of the church’s teachings was re-affirmed at their first service in July 1909, as the guest speaker rejected the conventional Christian doctrine of the Trinity, exclaiming ‘The ideas of three separate Persons in the Deity destroyed the very idea of Deity and the possibility of belief in it’ (New Church of Jerusalem, Brisbane Society, 1 March 1910). Services in this beautiful new building helped attract several high-profile members such as Justice Mein, the mining entrepreneur John Moffat of Irvinebank, and Alfred Davey, a member of Queensland’s Legislative Council (Brisbane Courier, 25 February 1909: 4; Telegraph, 22 July 1909: 5).

In 1913, the New Church, after considerable effort, acquired the ministerial services of Reverend Maro Underwood, from California. While he proved to be an enthusiastic preacher, Underwood was prone to interpersonal clashes with church leaders and resigned in October 1915. George Marchant did his best to once again fill in, at long last realising his vision of becoming a preacher. Transcripts of Marchant’s sermons reveal that he invested a great deal of time and energy into spreading the word (Telegraph, 16 May 1914: 10, and 27 October 1917: 16).

In 1920, when Marchant was in the United States on business, he encountered Reverend William Reece of Portland, Oregon. He later convinced him to come to Brisbane and take over as minister, arriving in August 1928 (Telegraph, 4 August 1928: 14). Marchant paid Reece’s first year’s stipend, provided a house for his family on McLeod Street, Herston, and even bought them a car. Reverend Reese, like his forerunner, encountered internal church disputes and in March 1930 returned to the US (New Church of Jerusalem, Brisbane Society, 29 November 1929, 22 January and 19 March 1930; Robinson, 1980: 90).

In 1923 the New Church on Ann Street was threatened by plans to build the Brisbane Club Hotel next door. For the Anglican Church, which owned this land and now intended to lease it for a public house, this move appears to have been sheer bastardry resulting from inter-church rivalry. The New Church lost this messy and expensive legal fight, and the hotel was built, causing them problems for decades to come (Daily Standard, 15 February 1923: 6 and 7 March 1923: 5; Brisbane Courier, 19 February 1923: 4; Telegraph, 8 March 1923: 4).

I believe that when I die as to my natural body, I shall rise in my spiritual body in the world of spirits, and be judged according to my works.

At the same time as this property dispute, New Church members adopted a new Creed that had a less explicitly ‘Swedenborgian’ flavour (New Church of Jerusalem, Brisbane Society, 24 January 1923):

I believe that our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ is the one God of heaven and earth, the Creator and Preserver of all things, and that in Him is the Divine Trinity of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

I believe that our Lord Jesus Christ came into the world for our redemption, and is now making His Second Advent through His Word with power and great glory.

I believe that the Sacred Scriptures are the inspired Word of God, the fountain of all wisdom for angels and men.

I believe that if I would be saved, I must, in the Lord’s strength, shun all evils as sins against Him, and walk in the way of His Commandments.

I believe that when I die as to my natural body, I shall rise in my spiritual body in the world of spirits, and be judged according to my works.

I believe that heaven is the home of all who die in childhood, and of those in every nation who fear God and work righteousness; and that hell is the chosen abode of those who love evil rather than good.

I believe in the universal and constant Providence of our Lord, whose tender mercies are over all His works.

In 1924 the New Church was rocked by a widely-publicised scandal of alleged sexual misconduct between senior members Constance Leech and William Wright. This affair was relished by the press where sexually-oriented scandals then, as now, titillated readers (Telegraph, 14 July 1924: 2).

When Reverend Reece resigned in 1930, George Marchant again filled in as their lay preacher. While Marchant was a good preacher, and well-respected within the congregation, his extensive business interests kept him busy and often away from Brisbane, with little time for pastoral care.

Joseph Leech, whose wife had been embroiled in the earlier scandal, took over as New Church Leader in March 1930. ‘He was not a powerful or eloquent preacher, but by his personality thoroughly endeared himself to the congregation, and was able to hold the Society together for the 30 years of his Leadership, conducting Services morning and evening each Sunday.’ Although Leech led the church, conducted baptisms, weddings and funerals, he had no formal qualification to do so (Robinson, 1980: 90–1; New Church of Jerusalem, Brisbane Society, 25 January 1931, and 4 August 1933).

In 1936 the New Church in Brisbane resigned from the Conference of The New Church in Australia over the ongoing liturgical dispute about the writing of Swedenborg, and whether they were the actual words of God or simply his interpretation of God’s word, alongside an arcane dispute over ‘the permissions, or degrees of evil outlined in Swedenborg’s Conjugal Love.’ The Brisbane Society did not re-join the national Conference until 1945 (Synnestveldt, 1970: 89-96; Robinson, 1980: 32–4, 91).

In September 1941, George Marchant, without whom the Brisbane New Church might well have collapsed, died. He had not only donated a small fortune to the New Church, but he also donated the land for Marchant Park, Chermside, helped finance the temperance Canberra Hotel in Edward Street, and donated money and land to establish the Garden Settlement (now known as Wheller Gardens), also at Chermside (Courier Mail, 6 September 1941: 5; New Church of Jerusalem, Brisbane Society, 12 September 1941).

Over the next fifteen years, without a pastor, the New Church struggled to maintain their property on Ann Street as membership dwindled. Joseph Leech, whose own health was failing, recommended in 1958 they take bold steps for renewal rather than terminal decline. The congregation decided to sell their Ann Street property and erect a new building in the suburbs (New Church of Jerusalem, Brisbane Society 13 June and 11 July 1958).

By this time members were concerned that ‘unless they find a minister from England the Society was in grave danger of extinction.’ In desperation, they approached Reverend Christopher Hasler, from Mauritius, who came to Brisbane. In 1960, the Ann Street property was sold to the Baptist Union for £42,000. With this money they bought land at 19–21 Agars Street, Rosalie (now Paddington) on which they built a modern brick church with caretaker’s cottage in 1961 (New Church of Jerusalem, Brisbane Society, 13 March 1959 and 7 February, 4 March, 8 April, 29 May, 16 June & 29 August 1960).

They also bought a house to serve as Reverend Hasler’s manse, at 68 Beryl Street, Holland Park. Costing £4,500, this house was on the opposite side of the city from where their new church was being built – an odd decision. Hasler seems to have been a competent and popular minister, but he moved to the UK in 1964, leaving the small congregation again struggling – albeit with new buildings (New Church of Jerusalem, Brisbane Society, 29 August 1960). Robinson concludes that Hasler and his predecessors Underwood and Reece, although ‘apparently well liked, and efficient and acceptable preachers … had little observable long-term effect on the fortunes or strength of the Society’ (Robinson, 1980: 93).

Soon after opening their new church in Rosalie, Reverend John Teed was recruited from Sydney. Teed revitalised and modernised the rather traditional congregation, introducing initiatives such Young People’s Camps at Binna Burra, and ‘home circle’ events for parishioners. This was a time of growth for the New Church but, after his nine years as minister, members agreed that Reverend Teed was no-longer ‘ministering to the whole of the Brisbane Society and a change of leadership would be beneficial’ (New Church of Jerusalem, Brisbane Society, 7 February and 23 October 1964; 13 July 1967; 11 June 1973).

Reverend Teed moved to Melbourne in 1973, and was temporarily replaced by two laymen and long-term members, Walter Young and Peter Larsen. In 1980, Reverend Bruce Williams, from Perth, took over as minister (Robinson, 1980: 96). He was in turn replaced in 1984 by Reverend Leslie Sheppard and Mr Ken Thompson, who shared duties until 2002 when Reverend Ian Arnold took over until 2013. Glen Alden filled in briefly until the present pastor, Darren Brunne, took over in 2014.

The Brisbane Society of the New Church today

In May 2015, the church sold their Rosalie property and, for several years, used the chapel of the Uniting Church Theological College for their services. In April 2021 a modern brick and glass building on Railway Terrace, Dutton Park, was purchased. Modest and contemporary on the exterior, inside the décor is greatly enhanced by a beautiful century-old font, dedicated to their great benefactor George Marchant.

Street signage informs us that The Brisbane Society of the New Church, as well as The New Jerusalem Church, ‘hold to the vision of a new spiritual age breaking in over the world. This vision is Bible-based and is the promise of the New Jerusalem descending from God out of heaven (Revelation Chapters 21 and 22).’ We also read how they ‘witness to a renewed Christianity which honours all religions that teach good ways and so point the way to heaven … Being ‘inspired by the Writings of Emanuel Swedenborg (1688–1772) we teach a deeper, spiritual meaning within the Bible.’

The Brisbane Society of the New Church now has about sixty members with about forty regularly attending services. As part of his outreach to young people, the church’s Reverend Darren Brunne has written Soul Warrior: The Battle Begins. On the rear cover we read

Has providence sent you here? Because right now in this moment you hold within your hands a Treasure map that can Change Your Life Forever … For within the pages of this book you will discover the 7 Timeless Steps that will lead you to the Peace, Happiness and Fulfilment you’ve been searching for your whole life. Time is of the essence. Begin your journey to Freedom today and read this book as if your life depended on it, because it just may.

In its various forms, the Brisbane Society of the New Church has had a fascinating religious tradition of almost 160 years. While surviving many setbacks, it never flourished with a large membership but has relied, like so many small community organisations, on the commitment of a relatively few, deeply committed members.

Reverend Brunne remains optimistic about the future, explaining that the New Church ‘provides tools to get to the spiritual sense of the word.’ They are ‘the way forward to help the New Jerusalem, coming down from heaven, land on earth.’ Their building is not itself sacred, but whenever ‘two or more of us meet here we make it a sacred space.’ His is a simple theology: ‘Every time you love someone you have just created a sacred moment’ (pers. comm., 26 July 2022).

Sources and further reading

Brunne, D. 2019. Soul Warrior: The Battle Begins. Memphis: Eternity Now Books.

Dingwall, E. 1962. Very Peculiar People: Portrait Studies in the Queer, the Abnormal, and the Uncanny. New Hyde Park, New York: University Books.

Fisher, R. 2000. ‘Sylvester Diggles: Brisbane’s Pioneer Musician, Scientist, Artist and New Churchman’, Journal of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland 17, 6: 271–86.

Fisher, R. 2010. ‘A Struggle for Existence: Planting the New Church of Jerusalem in Early Brisbane.’ In M. Harmes, L. Henderson and G. Colclough (eds), From Augustine to Anglicanism: The Anglican Church in Australia and Beyond. Brisbane: Augustine to Anglicanism Conference, 49–62.

Fisher, R. 2012. The Best of Colonial Brisbane. Brisbane: Brisbane History Group.

Jonsson, Inge. 1978. ‘Swedenborg, Emanuel’ Encyclopædia Britannica (Macropædia). 17: 854–56.

Metcalf, W., R. Kerr and I. Christie. 2011. ‘Woolloongabba Exemplars Commune.’ Queensland History Journal 21, 5: 319–35.

Muirden, B. 1974. ‘Pitman, Jacob (1810–1890)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, accessed 12 July 2022. https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/pitman-jacob-4402/text7177

Robinson, I.A. 1980. A History of the New Church in Australia 1832–1980. East Hawthorne: Excelsior.

Sharp, E. 1989. ‘Emanuel Swedenborg: Scientist and Seer.’ In N. Jarvis (ed.), Emanuel Swedenborg: Herald of a New Era. Sydney: The Swedenborg Lending Library.

Suzuki, D. 1996. Swedenborg: Buddha of the North. West Chester: Swedenborg Foundation.

Synnestveldt, S. 1970. The Essential Swedenborg. New York: Swedenborg Foundation.

Related articles