The Uniting Aboriginal and Islander Christian Congress

The Uniting Aboriginal and Islander Christian Congress commenced with great energy and idealism in the mid-1980s. It built on decades of activism and aimed to provide Aboriginal and Islander people and congregations in the Uniting Church, not only with a voice to the wider church, but also autonomy to express their life and faith within the overall framework of the Uniting Church’s theology and governance.

By John Harrison

This is a 20 minute read, published June 2024.

‘Probably the most historic and monumental step forward in the development of the Christian Church among Aboriginal and Islander Australians.’ That’s how journalist David Busch described the formal inauguration of the Uniting Aboriginal and Islander Christian Congress shortly after Pentecost in June 1985, at the fourth national Assembly of the Uniting Church.

The coming of the Congress gave Aboriginal and Islander people within the Uniting Church the right and the responsibility to determine their own distinctive styles of worship, witness, and service. Gone forever was the era of European Australians being missionaries to Aboriginal people.

The Assembly heard the Aboriginal and Islander people speak their desire to be responsible for ministry and mission among their own people. ‘We see ourselves as the children of Israel, being led from Egypt,’ explained the Rev. Charles Harris, soon to be Congress President. ‘Now at this Assembly we are at the shores of the Red Sea. We realise that on the other side is the wilderness, beyond that is the promised land.’

The Assembly resolution endorsing the establishment of the Congress was carried by acclamation and the singing of the doxology. As Aboriginal members of the Assembly filed back to their seats from the stage, the gathering started spontaneously to sing the hymn, A New Commandment I Give Unto You… ‘Some couldn’t sing as they choked back tears. There weren’t too many other items of business that ended with so many lumpy throats and moist eyes,’ reported journalist David Busch, with a touch of understatement (Harrison, 1967: 76).

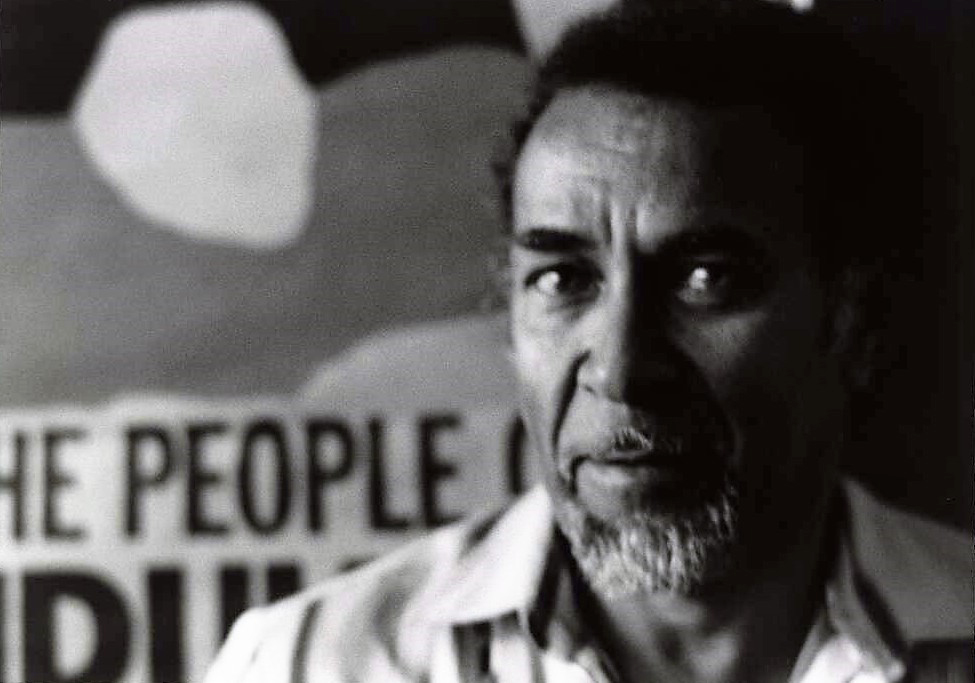

Rev. Djiniyini Gondarra (1945–), from Milingimbi, in eastern Arnhem Land, and Rev. Charles Harris (1931–1993) were Aboriginal clergy ordained in the Uniting Church, who were most influential in the formation of the national Uniting Aboriginal and Islander Christian Congress in 1985. ‘The Congress’, as it is colloquially known, is a structural expression within the Uniting Church of Aboriginal and Islander autonomy, authority, and identity.

Figure 1: Rev. Charles Harris, founder of the Uniting Aboriginal and Islander Congress (Uniting Church in Australia, Queensland Synod; Creative Commons).

Origins and Formation of the Congress

When the Uniting Church in Australia was formed in 1977 by the Presbyterian, Methodist and Congregational Churches, a number of Aboriginal congregations came into that union. Some were in urban centres such as Brisbane and Townsville, and a number in remote Indigenous communities such as Aurukun and Mornington Island in Queensland, and Milingimbi and Galiwin’ku in Arnhem Land. The Uniting Church’s engagement, and that of its predecessor denominations, with the Torres Strait is almost incidental. The Congregationalist London Missionary Society arrived in the Torres Strait in 1871 (The Coming of the Light) and handed over its work to the Church of England in Australia in 1915. In 1977 Aurukun and Mornington Island were still missions run by non-Indigenous clerical administrators.

Aurukun was established by Moravian missionaries auspiced by the Presbyterian Church in 1904, and Mornington Island by the Presbyterians in 1914. Mapoon, the original Moravian mission established in 1891, was closed in controversial circumstances in 1963. The best account of that closure is Geoff Wharton’s 1996 UQ thesis The Day They Burned Mapoon. Aurukun and Mornington Island transitioned from being church-run missions to being autonomous local authorities under controversial circumstances in 1978, with the church only providing pastoral care though ministerial agents.

Weipa Mission, established by Moravian missionaries in 1898, had been handed over to the Queensland Government in 1966, but an Aboriginal congregation continued at the community on the old mission site at Jessica Point (Weipa South), now known as Napranum. There were also Aboriginal congregations in other states, including Western Australia, where the church has also run missions.

With the advent of the Congress in Queensland in 1985, Aboriginal congregations at Aurukun, Napranum, Mornington Island, Cairns-Edmonton-Gordonvale, Townsville (West End), and Zillmere were formed into what the then Queensland Synod Secretary, the Rev. Duncan Harrison, described as ‘a sociological presbytery’. In the polity of the Presbyterian, and then Uniting Church, a presbytery is a regional body charged with oversight of the parishes within its bounds, a form, as some have described it, of ‘corporate episcopacy’. Presbyteries are traditionally geographical, and the notion of a ‘sociological presbytery’ was a highly unusual and innovative approach to church polity. With this arrangement, the Aboriginal congregations were grouped into what became known as Calvary Presbytery, with offices in Townsville.

The Congress evolved after several years of deliberation, consultation, and prayer by the Aboriginal people themselves and the wider church councils, commissions, and committees, beginning with a national gathering of Aboriginal Christians at Crystal Creek, outside Townsville, in August 1982. This was followed by a further meeting at Galiwinku on Elcho Island in Arnhem Land in August 1983.

The deeper roots of the Congress lie in the spiritual renewal that began sweeping throughout Aboriginal communities from Galiwinku in 1978 and 1979. The revival began in small prayer groups of Aboriginal and white Christians at Elcho Island and was given impetus by the visit of charismatic evangelist the Rev. Dan Armstrong of O’Connor Uniting Church in Canberra in May 1979.

By 1980, the revival had spread to the Pitjantjatjara people, whose lands occupied areas of the southern Northern Territory and northern South Australia, and beyond that into the Aboriginal groups in the western desert and to the east among some of the Queensland Aboriginal communities. In 1984, one year before the formal establishment of the UAICC, remote Aurukun on the western coast of Cape York became the site of a unique achievement — the translation of the New Testament into the Wik language, which was accomplished by two Bible translators from the Summer Institute of Linguistics working with Wik speaking women at Aurukun from1962.

The formation of the Congress in 1985 was made possible by several factors. The Arnhem Land revival was significant, but must be coupled with other events also of spiritual importance to Aboriginal people. The move back to their traditional lands along with successful land rights claims in the Northern Territory and South Australia by Aboriginal people had been a liberating experience. It is difficult for non-Indigenous Australians to understand the spiritual link Aboriginal people, including Christian Aboriginal people, have to the land. There is a link between the spiritual liberation experienced by Aboriginal people through the spreading flame of the Arnhem Land revival throughout northern and central Australia and Aboriginal people’s reclaiming of their land.

At the four-day Galiwinku meeting, seventy representatives from across Australia met for ‘prayer, praise, proclamation and discussion’ (Harrison 1986: 79) The non-Indigenous people present did not speak unless invited; it was an occasion for Aboriginal and Islander people to seek and hear the will of God. At the conclusion of the conference, Charles Harris, who had criss-crossed the country consulting with Aboriginal groups about the Congress, said, ‘History has been created. God’s purpose has been fulfilled. Let us break down the walls of racism. As we go forwards the gates of hell will not prevail against us’ (Harrison 1986: 77).

One of the non-Indigenous Uniting Church clergymen present, the Rev. Dr Robert Bos, wrote subsequently, ‘It is not a question of whether we give permission to Aboriginal and Islander people to do this. The only question is whether we will make room for them to do it within the Uniting Church or not’ (Harrison 1986: 77). In Queensland, the church authorities worked to devise a structure which maximised Aboriginal autonomy. As Synod Secretary the Rev. Duncan Harrison explained at the time (Harrison & Harrison 2003: 110):

We are planning an approach which will give our Queensland regional committee functions similar to those of a presbytery in oversight of ministers and congregations and pastoral care. The Congress will relate to the Synod in ways similar to those of other presbyteries and probably be represented in the Synod as other presbyteries are.

The involvement of different Aboriginal communities in the Congress is reflected in the design of its logo. From Aurukun came two message sticks, formed into a cross to represent the proclamation of the gospel of good tidings. The Galiwinku people of Elcho Island gave the Wanguri fighting stick represented at the top of the logo. It has important historical associations with Milingimbi. One of the earliest Christian converts in the area, Harry Magarrawala, always carried the stick as a sign of peace and reconciliation, especially in disputes. The bird represents the Holy Spirit and the tongues of fire; the black and white hands symbolise unity and renewal in Arnhem Land. The colours are the traditional Aboriginal colours of red, black, and yellow.

Key Leadership Figures

During its existence, the Congress was led by a sequence of key figures in the history of Indigenous Christianity in Queensland and Australia. One of the most interesting aspects of this leadership is that both Charles Harris and Bill Hollingsworth originally came from the Pentecostal tradition. Clearly, both found that the resources and structures of the Uniting Church supported their aspirations more than the unstructured spontaneity of Pentecostalism, although their Pentecostal roots were obvious in their approach to worship and, to some extent, theology.

Born in Ingham in North Queensland and having both Torres Strait and Aboriginal ancestry, Charles Harris grew up in the Pentecostal tradition as a member of the Assemblies of God denomination (Blake, 2017). The definitive account of his life and work can be found in William Emilsen’s 2019 biography Charles Harris: A Struggle for Justice. Harris worked as a canecutter and railway labourer, before attending the Commonwealth Bible College in Brisbane (1957–1959). Becoming a travelling evangelist in northern NSW, he met and married Dorothy Roberts, and the couple moved back to Ingham.

In the 1960s he became involved in the Ingham Methodist Church under the influence of Rev. Ed Smith. He joined the ministry team there and transferred to Hermit Park in Townsville where the church was establishing a ministry among Aboriginal and Islander people. In 1973 he returned to Brisbane to lead an Aboriginal congregation at Paddington auspiced by Wesley Central Mission. While there he completed further study at Alcorn College and Nungalinya College in Darwin and was ordained as a Uniting Church minister in 1980.

During the 1980s Charles pursued his vision of an autonomous national body of Aboriginal and Islander congregations within the structures of the Uniting Church. That vision was realised with the creation of the UAICC in 1985, and Charles became the Congress’s first national president, based in the national Uniting Church Assembly office in Sydney. In 1988, he organised the Long March for Freedom, Justice, and Hope in Sydney. Held on January 26, 1988, the event, attended by over 50,000 people, recognised that the Bicentennial was not a cause for celebration. In 1989 Charles retired on the grounds of ill-health and died in Townsville in 1993.

Figure 3: Rev. Charles Harris speaks at a 1988 Bicentennial protest, Parliament House Canberra (Uniting Church in Australia, Queensland Synod; Creative Commons).

Born in Mossman, Bill Hollingsworth (1933–2019) lived and worked for most of his life in the towns and villages in the Cairns region. His mother, a person of deep and abiding Christian faith, was born on Batavia Downs, a cattle property on Cape York. At six years of age, she was removed to the Anglican Mission at Yarrabah, becoming part of the Stolen Generations. Bill’s father died in an accident when he was ten years old. Bill spent many of his early years working as a labourer in the sugar industry in North Queensland, before working with the Flying Doctor as a drug and rehabilitation counsellor in the early 1980s and as an elected North Queensland representative for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC).

All this time his faith remained undiminished and, when the UAICC was formed in 1985, he took a leadership role in the Cairns-Gordonvale-Edmonton area, retiring in 2002 at age 69. He was also an appointed member of the national Council for Reconciliation, writing in 2013, ‘as a Christian, I am the product of reconciliation. Romans 5:10–11 tells us that when we were still enemies, we were reconciled to God by the death of his son, replacing the enmity that existed between God and humankind with peace and restored relationship’ (Hollingworth 2013).

Born in Bundaberg in 1954, Shayne Blackman worked as a manual labourer after leaving school aged 14. After study at Darwin-based Nungalinya College, he was ordained in 1984 and immediately installed as the inaugural chair of Calvary Presbytery, which was constituted that day. As the key leader of Calvary Presbytery, Shayne drove a number of initiatives in North Queensland from the site at Condon, in Townsville, retiring in 2014, having also served as national chair of the UAICC. He was succeeded by Dennis Corowa, who formerly had served in the Indigenous congregation at West End in Townsville, also known as ‘Restoration Inn’. Born in Murwillumbah, Corowa lived in Mackay in his early years and in 1989 began to participate in ministry in Townsville. After ordination in 1994 and his work in Townsville, he succeeded Blackman as Chair of Calvary Presbytery and as national UAICC chair.

Dennis Corowa was thoughtful about the relationship between Christianity and Aboriginal culture. He was a contributor to a volume called Rainbow Spirit Theology: Towards An Australian Aboriginal Theology published by Harper Collins in 1997. In 2005 he articulated this relationship (Archie, 19977: 27).

God determined that Australia would first be occupied by the Aboriginal and Islander peoples. We are the first peoples of this land. We are part of nature — part of God’s creation, not apart from it.

As Indigenous people, we look at God in nature and our spiritual dreaming. Spiritually through our dreaming, we are linked to nature through our totems. It is about relationship and survival, as our dreaming is linked to plants, land, animals, birds and fish.

Silas Wolmby was a Wik elder and an ordained Uniting Church Minister. His ministry had a significant impact on the non-Aboriginal church. He challenged its prejudice and racism by his words and presence. He was not afraid to put the case for his people to government and the wider community as Aurukun and other communities struggled for self-determination and land rights. He was a strong supporter of the worshipping life of the Aurukun Uniting Church — encouraging younger leaders to grow in leadership and helping with funerals and baptisms. During the Aurukun revival, Silas played an important role in communicating his visions and dreams of what God was doing amongst them, and in hosting family fellowships of worship and dancing.

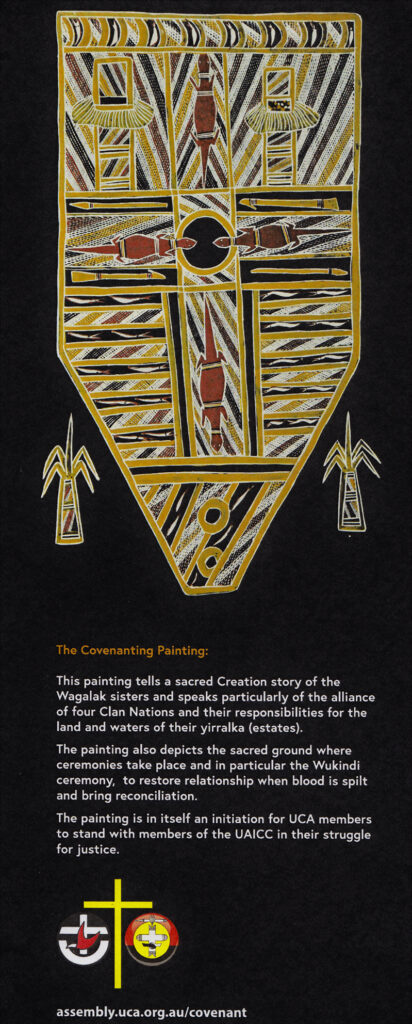

The Congress in Action: the Covenant Agreement and the Calvary Presbytery

Perhaps the most significant national event in the life of the UAICC came in 1994 with the signing of a Covenant Agreement between the Uniting Church and the UAICC, which defined the relationship between the two bodies, and apologised ‘for all those wrongs done knowingly or unknowingly to your people by the Church, and seek(s) your forgiveness.’ For its part, the chair of the UAICC at the time, Pastor Bill Hollingsworth, responded (UAICC Covenant):

It is good and right that the church should repent of any of its actions in support of a policy that violently discriminated against and oppressed God’s stewards of this land. Contrary to the belief of the invaders that they had a divine right to take possession of this land as their own, the God of righteousness, truth and justice has sustained us with the belief that one day we would be recognised as the true stewards of this land. This has come to pass through the High Court decision which was handed down in the Mabo case.

Queensland, the national Congress took the form of Calvary Presbytery. A number of its activities were located on a greenfield site at Condon in Townsville, made possible by a philanthropic donation from Melbourne business figure Hank Young. The 3.2 hectare site was just over the road from the original North Queensland Cowboys rugby league stadium in Townsville, and included an aged care facility (Elders Village), the administrative offices of Calvary Presbytery, the operations of the Yalga Binbi community development training facility (which had also operated out of Cairns), and Shalom College, a primary and secondary boarding school which catered for children from remote communities in Cape York established in 1992.

Calvary Presbytery also assumed responsibility for the land of the former Crystal Creek youth camp at Paluma, north of Townsville, using the site as an outdoor education facility for Shalom College students. The site was made over to Calvary Presbytery by the Uniting Church Synod as a gesture of reconciliation.

Congress Community Development Education Unit (CCDEU) was the corporate entity through which these and other Calvary Presbytery activities were managed. As such, it was independent of the Uniting Church in Australia Property Trust (Q), the legal entity established under an act of parliament to hold all assets of the church. As a limited liability company, CCEDU’s activities were not backed by the assets of the Trust, but it gave the directors, all of whom were appointed by Calvary Presbytery, considerable autonomy, which was consistent with the Uniting Church’s policy of Indigenous empowerment.

The end of Calvary

Despite all the rhetoric about Indigenous autonomy and cross-cultural partnership and support, time was running out for this unique expression of an Indigenous voice within the Queensland Synod of the Uniting Church. In a sign of mounting challenges, the CCDEU was placed into liquidation in 2012 and the principal asset, Shalom College, handed over to the Queensland Synod to operate. After serious allegations of sexual assault at the Shalom College boarding school were aired at the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, the Uniting Church decided to withdraw from the College after finding it could not guarantee the safety of the students.. The secondary/boarding part of the School was closed in 2017, and the primary school sold to the Baptist Church community service agency Carinity in 2018.

By 2017 relationships between the UAICC, as represented by Shayne Blackman, and the Queensland Synod, as represented by Moderator David Baker, had broken down irretrievably. A complaint by Blackman that the Moderator has breached the Code of Ethics for clergy was not sustained by the majority non-Indigenous membership of the Council of Synod. Meanwhile the retirements of Shayne Blackman in 2014, Dennis Corowa in 2019, and the death of Bill Hollingsworth, aged 86, in 2019, left a leadership void in the UAICC in Queensland. Dennis Corowa was the only ordained Indigenous member of the 2019 Synod in Session. The presbytery was aware of the issue, reporting to the 2019 Synod in Session, ‘The gaps in ministerial presence in Calvary’s congregations…highlights the difficulty in filling the needs of ministry in remote areas.’ (Calvary Presbytery 2019: 2).

In 2020 Calvary Presbytery was dissolved by a decision of the Queensland Synod, and the Aboriginal congregations in North Queensland (Aurukun, Mornington Island, Napranum, Mapoon, Gordonvale, and West End Townsville) were incorporated into the existing Presbytery of North Queensland, which was renamed Carpentaria Presbytery. The decision was described by the UAICC to the national Assembly in 2021 as ‘very disappointing’. ‘This came as a complete shock … and highlights the need for Synod leaders to be talking not only to their local leaders but also to the National Office of Congress’ (Calvary Presbytery 2019: 2).

The then Moderator, David Baker, in March 2020 described the merger of Calvary Presbytery as ‘a genuine step towards reconciliation.’ He continued (Baker, 2020):

The Carpentaria Presbytery will provide additional capacity and governance structures to help implement mission initiatives and increase engagement between First and Second Peoples … Leaders of the communities of the Cape and the Gulf have expressed strong support for this new venture.

Veteran Aboriginal minister Dennis Corowa was reported as saying, ‘While I am disappointed, I understand the rationale’ (Anon, 2020).

The merger occurred at the same time as the Queensland Synod was developing a state-wide Reconciliation Plan with a focus on respect and autonomy for First Nations peoples, and the promotion of the 1994 Covenant between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and the rest of the Uniting Church as part of that process. Incongruously, in May 2019 the Queensland Synod ratified a Covenant Action Plan to build up the original 1994 Covenant. Its three central principles were (O’Callaghan, 2019):

Our work together in this space will be built upon the posture of relationship-building.

Our work in this space will exemplify the posture of taking time and patience, alongside holding in tension identified and measurable outcomes.

Our work in this space will intentionally model the posture of ‘building bridges from both ends’.

In the past decade there has been a steady retreat by the non-Indigenous leadership of the Uniting Church in Queensland from the ideals and aspirations of the 1980s. However, in May 2021, the then Synod Moderator, Rev. Andrew Gunton, attempted to recover some of the lost reputational capital of the Synod by convening a summit-style meeting in Cairns of Indigenous people from across the state and key Uniting Church agency representatives (O’Callaghan, 2021). It remains to be seen how the original vision of the UAICC, and the aspirations and autonomy of the Indigenous congregations, can be realised with the dismantling of the structures of Calvary Presbytery

Sources and further reading

Anon. 2020. ‘Presbytery amalgamation sets new course for reconciliation.’ March 13, 2020.Journey (Online). https://journeyonline.com.au/scoop/presbytery-amalgamation-sets-new-course-for-reconciliation/

Archie, N.J. (et al.). 1997. Rainbow spirit theology: Towards an Australian Aboriginal theology. Sydney, Harper Collins.

Baker D., March 2020. ‘Statement – Carpentaria Presbytery.’ https://ucaqld.com.au/statements/statement-carpentaria-presbytery/

Blake, Thom. 2017. ‘Harris, Charles Enoch (1931–1993).’ Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, https://ia.anu.edu.au/biography/harris-charles-enoch-18183/text29753

Calvary Presbytery. 2019. Synod in Session.

Corowa, D. 2005. ‘Indigenous Australians read the Bible through different eyes.’ Journey (Online), August 11, 2005. https://journeyonline.com.au/features/indigenous-australians-read-the-bible-through-different-eyes/

Emilsen, William. 2019 Charles Harris: A Struggle for Justice. MediaCom.

Harrison, D. and J. Harrison. 2003. ‘Queensland.’ In W. Emilsen and S. Emilsen (eds), The Uniting Church in Australia. The first 25 years. Armadale: Circa.

Harrison, J. 1986. Baptism of Fire. Melbourne, Uniting Church Press.

Hollingworth, B. 2013. On the way to reconciliation. Journey (Online), June 7, 2013. https://journeyonline.com.au/opinion/on-the-way-to-reconciliation/

O’Callaghan, J. 2019. ‘Covenant Action Plan: a momentous milestone.’. Journey (Online), June 12, 2019. https://journeyonline.com.au/queensland-synod-news/covenant-action-plan-a-momentous-milestone/

O’Callaghan, J. 2021. “First Moderator-hosted gathering the beginning of a journey towards self-determination”. Journey (Online) June 9, 2021. https://journeyonline.com.au/queensland-synod-news/first-moderator-hosted-uaicc-gathering-the-beginning-of-a-journey-towards-self-determination/

UAICC Covenant: https://assembly.uca.org.au/images/resources/Covenanting/Covenant-with-UAICC-A2-poster.pdf.

Wharton, Geoff. 1996. ‘The Day They Burned Mapoon.’ PhD dissertation, University of Queensland.

Related articles