Synagogues in the Sunshine: The Gold Coast Jewish community

With a handful of other Jewish families, the Goldsteins established the Gold Coast’s first organised Jewish community. Although small in numbers, it soon became unique, vibrant, and culturally rich.

John Goldstein was born on a boat in the middle of the Red Sea as his parents were escaping Kristallnacht. Statistically speaking, John and his parents, a young German-Jewish couple, should not have escaped Europe alive that November of 1938. During a stopover in Hong Kong, his parents, Julius and Paula, visited a synagogue on a hill and took the opportunity to have John circumcised, maintaining their commitment to Jewish traditions. Remarkably and against all odds, they arrived in the sunlit streets of Brisbane in January 1939 having been sponsored into Australia by the Jewish Welfare Society (Goldstein, J. Interview, 2021).

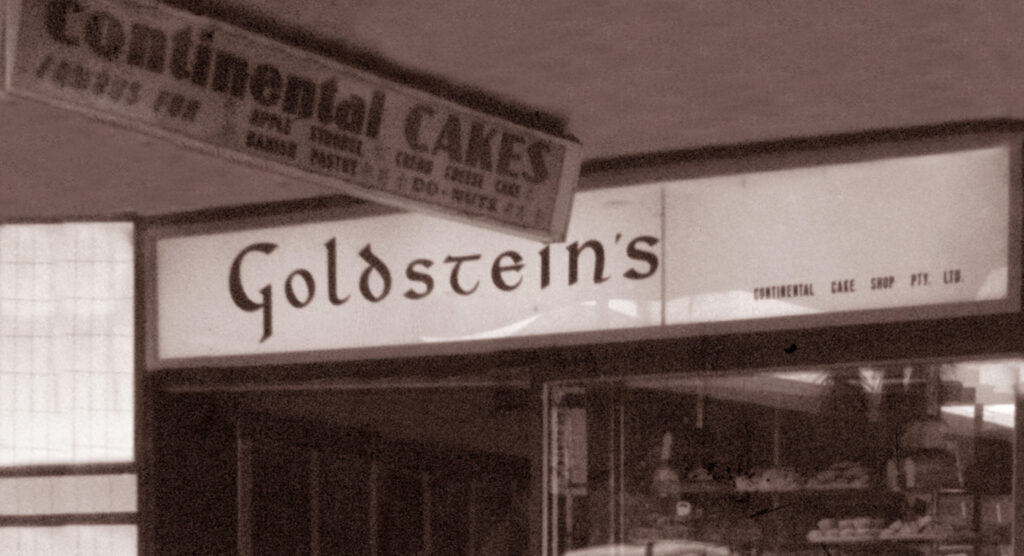

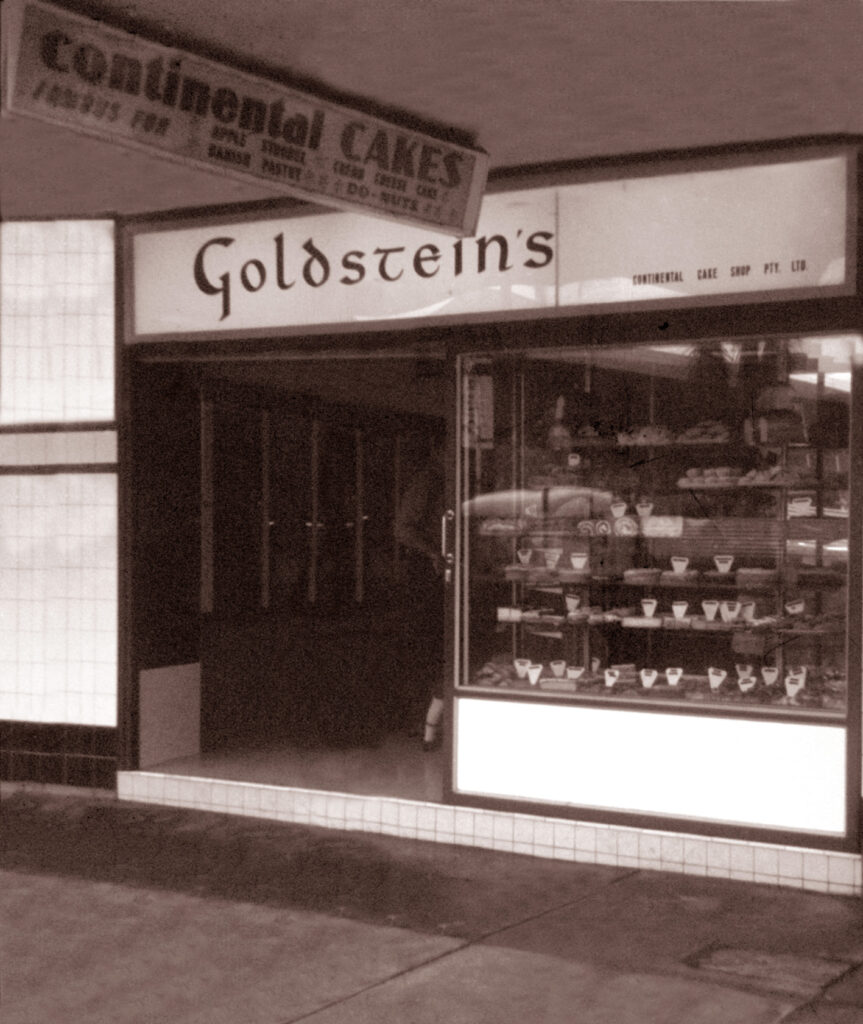

The Society loaned the Goldsteins £50 to start their new life. Julius was a pastry chef by trade and when, in 1944, an old cake shop in Brisbane’s Roma Street became available, he seized on the opportunity. Julius’s Busy Bee Cake Shop began serving continental European pastries and cakes and quickly became ‘the’ Jewish bakery. The bakery’s busiest day was Friday when it baked many traditional and breads in time for the sabbath. Jewish residents of the Gold Coast would travel the then two-and-a-half-hour drive to treat themselves to the nostalgic European flavours knowing that it was baked kosher according to Jewish laws and rituals.

Thirteen years later, the family packed up their business and home to enjoy the more relaxed lifestyle of the South Coast (now Gold Coast), where a small Jewish community was forming in concert with a growing population of Jewish tourists. The business’s name was changed to Goldsteins, and it went on to being one of Queensland’s biggest bakery chains. To this day, little do people know that they are eating baked goods with Jewish recipes that survived the Holocaust before thriving in Australia. John remains a stalwart of the Jewish community on the Gold Coast. Together with a handful of other Jewish families, the Goldsteins established the Gold Coast’s first organised Jewish community. Although small in numbers, it soon became unique, vibrant, and culturally rich.

Figure 3: Paula and her two sons pose for a photograph at the bakery. Left to right: Frank Goldstein, Paula Goldstein, John Goldstein (Goldstein's Bakery).

Holidays, business opportunities, and the transient community

During and after the Second World War, the Gold Coast, especially Surfers Paradise, was fast becoming a pole star for many residents of Melbourne and Sydney escaping their cold winters. Among this growing seasonal population were hundreds of Jewish people, including honeymooners, exhausted interstate businesspeople, eager entrepreneurs, and ex-servicemen, some of whom were Holocaust survivors (Sydney Jewish News, 1949: 10; Hebrew Standard of Australasia, 1949: 6). The Jewish locals at the time recall the ‘southerners’ famously sitting on the public benches on the beachfront playing cards and chatting away in Yiddish (The Australia Jewish News, 1959: 12). They arrived every winter like clockwork, generating a four or fivefold increase to the local Jewish population. This period always aligned with the school holidays, which was also the time of many prominent and sacred Jewish holidays, such as Yom Kippur and Rosh Hashana. With the increase in Jewish holidaymakers from 1940 to 1960, a small grassroots movement developed advocating for a holiday destination that better accommodated the practice of Judaism. Records show that numerous rabbis spent many winters holidaying on the Gold Coast (The Australia Jewish News, 1964: 18). A shared culture, history, and faith brought the community together no matter the circumstances, reinforcing for many the nature of the Jewish faith and its survival.

These early tourists who chased the laid-back beach holiday vibes brought their religiosity with them. Though far from home, they sought comfort in the familiar, where there was no need to explain kashrut, wearing a kippah, or the lighting of shabbat candles. Some would bring kosher food, others purchased apartments to ensure they had a kosher kitchen — a facet of Judaism not heavily present in the local Jewish families at the time. Year after year, upon returning for their sun-kissed tans, the nostalgia of sharing religious observances in a communal setting grew stronger.

John Goldstein’s younger brother Frank, another local member of the Jewish community, recalls that the growing Jewish population was not met with complete acceptance. It was not unusual to hear derogatory remarks in the streets, such as ‘Here comes the four by twos’, a Cockney rhyming slang referring to Jews (Goldstein, F. Interview, 2021). Most people shrugged it off and the remarks faded away.

Business opportunities drew to the Gold Coast the likes of Stanley Korman and Sonia Grodeck. Both Stanley and Sonia were anxious to make the Gold Coast an international destination. In the late 1950s, Stanley famously revamped and modernized the Surfers Paradise Hotel, which was just a pub in the 1930s, a development that included the construction of several street-level shops for rent on Cavill Avenue (Korman, Interview, 2021). Members of the community in the Cavill Avenue strip and across the new town were often closely connected. On Cavill Avenue alone, Stanley had a niece by marriage, Geulah Korman, whose fashion shop, Riviera Casuals, amplified Surface Paradise’s growing cosmopolitan appeal (McRobbie, 1984). Harry Samuel owned up to five pharmacies on the coast, including one adjacent to the Beer Garden in Cavill Avenue (Samuel, Interview, 2021). Jews were found in the hospitality scene, such as the Pahoffs, who owned El Cappuccino, and the Travers, who operated The Little Hut. Jewish visitors were often found flocking around The Nosh Bar, nosh being a Yiddish word meaning ’to snack’, where the Jewish-Austrian owners enticed them with the nostalgic flavours of Jewish-European dishes.

With each holiday, the call from interstate travellers to enhance Jewish communal life became more forceful and compelling. Holidaymakers, who far outnumbered locals, convinced the local Jewish community of the merits of establishing a Jewish congregation. The small number of local families also realised that being Jewish on the Gold Coast could no longer be taken for granted, as it perhaps had been in the larger and well-established Jewish communities they had migrated from.

Community

The Samuel family had only been living in the heart of Surfers Paradise for a year when they put their hands up to host the Gold Coast’s first communal shabbat service in their own living room. Stripping it of its furniture, they turned the space into a make-shift synagogue (Samuel, Interview, 2021). All the necessary religious materials and resources were loaned from the Brisbane Hebrew Congregation, whose synagogue is in Margaret Street in the heart of the city. The unexpectedly large crowd was an assortment of Jews from all walks of life: orthodox, liberal, men who had married out, and anyone in between. Despite their varied religious backgrounds, they shared a common interest in coming together as Jewish people and giving their children the opportunity of a Jewish life. On a Friday night in 1958 in a ‘Mushroom coloured house’ on Ferny Avenue opposite Chevron Island, the first authorised Jewish religious service took place on the Gold Coast (The Gold Coast News, 1958).

John Goldstein was only nineteen at the time when his family helped to put the service together. When asked how he perceived this momentous occasion, he said:

It felt strange. The Jewish people who came up from Sydney and Melbourne were very fluent and much more religious than what we were. We were the minority there. When I say minority, we were the locals and they were the visitors that made up numbers. From then on, we always had a minyan somehow or rather.

Following this event and in response to increased calls for Jewish services (Fabian, 1981: 97–115), on the 16th September 1958 all resident Jewish families of the Gold Coast were invited to attend a meeting at Ocean Court, a beautiful, white, resort-like guesthouse that once stood on the corner of Cavill Avenue and the Esplanade. Twelve local residents attended with a clear agenda: to establish a Jewish congregation for Surfers Paradise and surrounding districts. They left Ocean Court that day having officially formed the Gold Coast’s first ever congregation.

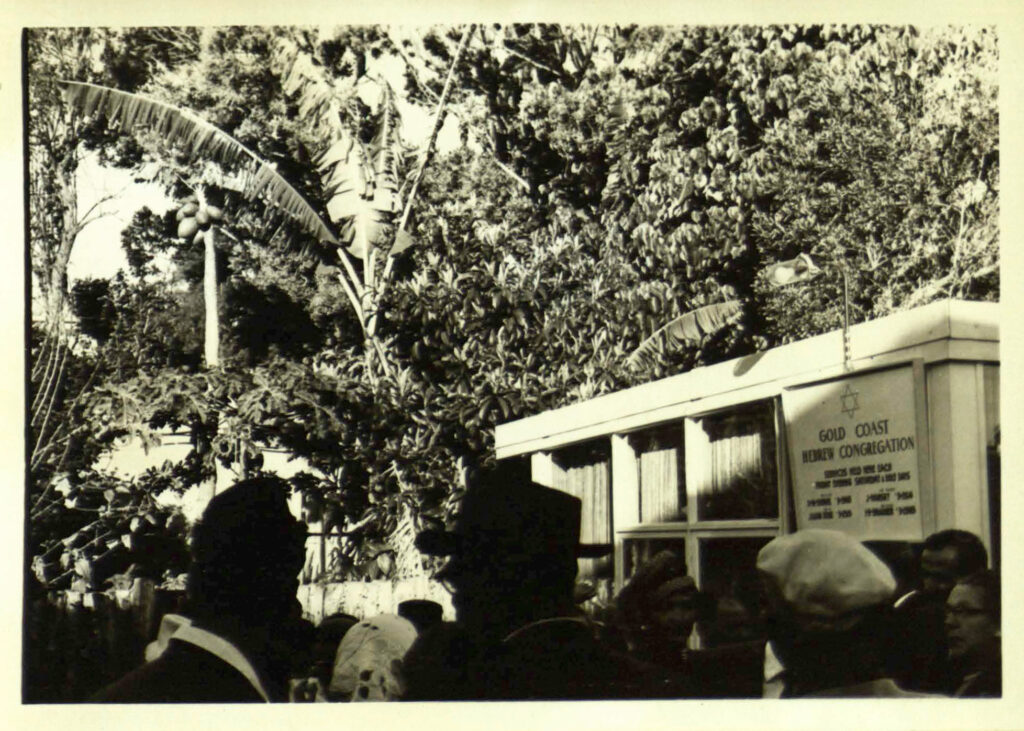

Figure 5: Consecration day, 3 September 1961, Hamilton Avenue, Surfers Paradise (Sydney Fisher Library).

Every congregation wants a synagogue

Shabbat services and special Jewish occasions continued in church halls and private homes and hotel function rooms offered by local Jewish families and proprietors. Then, in June 1961, a tiny cottage in Hamilton Avenue Surfers Paradise with spacious grounds was listed for sale. The Gold Coast Jewish congregation purchased the property. The difficult years seemed over; many years of effort had finally coalesced into a Jewish sanctuary. According to Rabbi Fabian, the time that had elapsed between the formation of the congregation and the consecration of the Synagogue was a record in Australian synagogue history (Fabian, 1981: 97–115). Remarkably, only sixteen years had passed between its consecration and the abhorrent demolition of Synagogues and the annihilation of six million Jews in the Holocaust.

Within three short months, the small, old cottage was transformed into a modest, self-contained synagogue, with a prayer hall, social hall and a classroom. Decorated with Stars of David and Mezuzahs, the building stood out in the little Christian-dominated beach town of the Gold Coast. On 3 September 1961, in perfect Surfers Paradise sunshine, around 200 guests listened to the beautiful prayers conducted by Brisbane Hebrew Congregation leaders, Rabbi Fabian and Mr Y. Amitzur, a teacher of Hebrew, as they consecrated Queensland’s newest non-Metropolitan synagogue (Fabian, 1981: 97–115).

The first year after consecration was marked by further significant historical developments. One particularly important event was a visit from the Chief Rabbi of Great Britain and the Commonwealth, Dr Israel Brodie (The Australian Jewish News, 1962: 21). During his second Pastoral Tour of Australia in February 1962, he visited the new synagogue site and gave a memorable address to an overflowing crowd.

Another highlight in that inaugural year was the Gold Coast’s first Bar Mitzvah celebration, an occasion that highlighted the community’s purpose and strength by providing their members with the opportunity to partake in one of Judaism’s most traditional ceremonies.

By the mid- 1960s, the majority of rabbis serving in Australia had paid a courtesy visit to Australia’s youngest congregation. Some received special mention in The Australian Jewish News, including Rabbi Dr I. Porush, the Chief Minister of Sydney’s Great Synagogue and one of the founding fathers of the post-war Australian Jewish community (Kleerekoper, 2022), and Rabbi Dr S. Coleman, the rabbi of the South Head Synagogue in Sydney and Vice-President of the NSW Board of Jewish Education. In 1966, the congregation made a momentous decision to appoint Rabbi Ludwig as the Gold Coast’s first permanent Jewish Minister. His mental and physical fragility after enduring the horrors of the holocaust limited him to a part-time role and periods of leave, but his strength and dedication to the community as its first official rabbi have never been forgotten. The decision to engage a permanent rabbi was celebrated in the congregation’s fifth annual report: ‘The appointment of Rabbi W. Ludwig as our Minister was a momentous move because of the relief it gave the board of the endless problem of conducting regular services, particularly over the Yom Tovim’ (Samuel, 1966).

The search for spiritual leaders

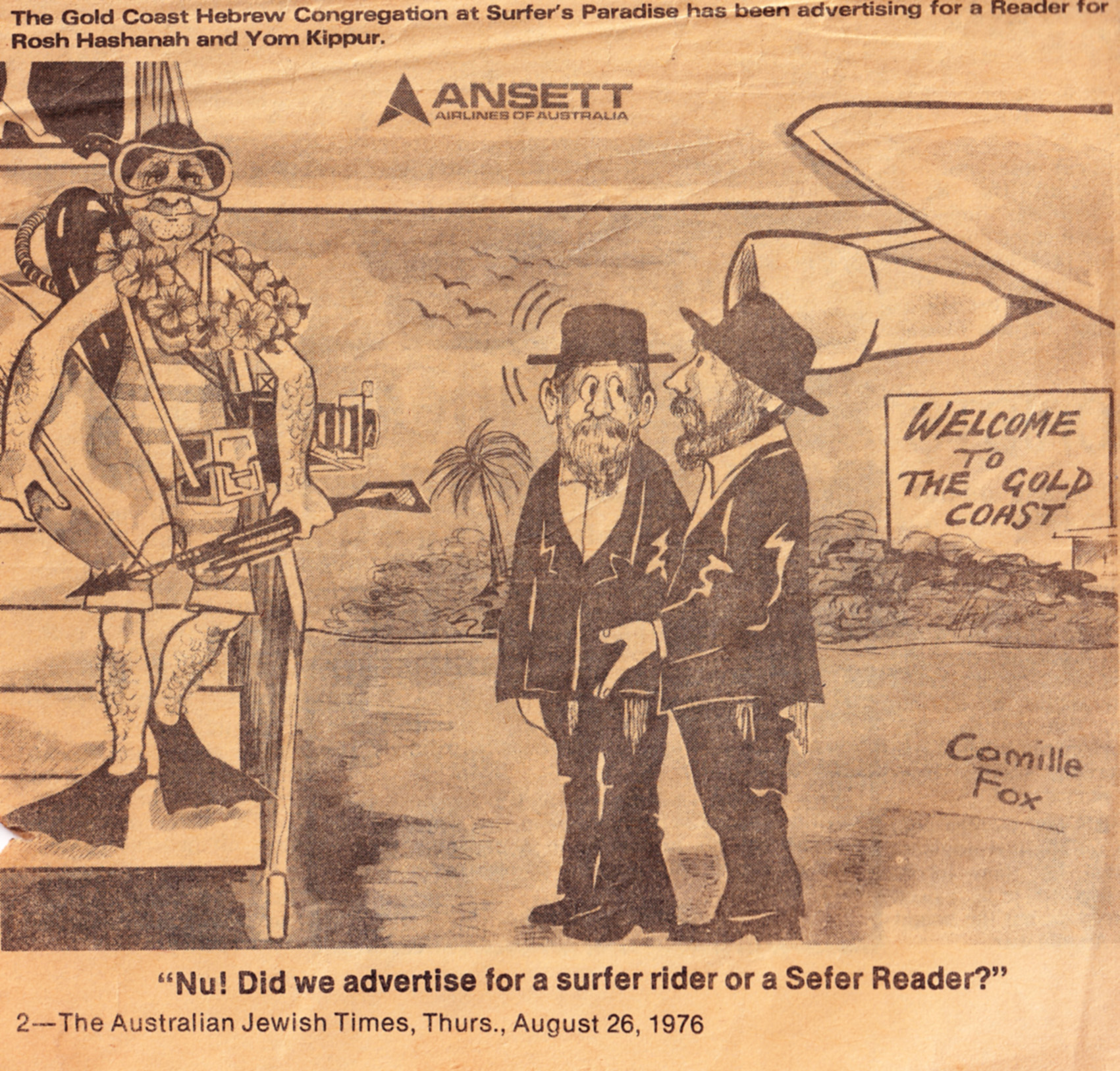

Due to poor health, Ludwig could no longer meet the needs of the growing community. Low funds meant that they could only offer a post for the winter high holiday season. The congregation advertised the new position in The Australian Jewish Times.

Figure 8: A satirical cartoon by Camille Fox, published in the Australian Jewish Times after the Gold Coast Hebrew Congregation advertised for a new rabbi (The Australian Jewish Times, 1976, used with artist's permission).

The congregation went on to employ four more rabbis over the decades, including the incumbent Rabbi Nir Gurevitch. In 1993, he and his wife Dina traded their snowy New York winters for sun-drenched Gold Coast beaches and have served as Spiritual guides ever since. One of the major achievements of the Hebrew Congregation is attributed to Rabbi Gurevitch — the constructing of a Mikveh, a bath used for ritual purification.

Gurevitch, the driving force behind the project, admits that the execution of the Mikveh was no easy feat (Gurevitch, Interview, 2021). A builder from a small Brisbane construction company got to work metres below the ground. As he delicately weaved his tools through pipes and cement, Gurevitch and Rabbi Joesph Gutnick, the supervising rabbi from Melbourne, were awestruck by how easily he managed to navigate his way through the job. Gurevitch owes it to the serendipitous fact that the builder, although raised as a Seventh Day Adventist, had a Jewish mother, a detail the builder shared with the rabbis when they were informing him that the blueprint needed to be followed precisely to ensure its sacredness and kashrut. The Gold Coast Mikveh is unique to this community, because in most other communities it is a separate establishment. Volunteer run, the Mikveh is an integral part of the Hebrew Congregation, serving not only local families, but observant Jewish men and women from Brisbane, Byron Bay, and many other places, who travel to undergo the act of ritual purity.

The Gold Coast Mikveh is unique to this community, because in most other communities it is a separate establishment. Volunteer run, the Mikveh is an integral part of the Hebrew Congregation, serving not only local families, but observant Jewish men and women from Brisbane, Byron Bay, and many other places, who travel to undergo the act of ritual purity.

There were many other developments led by the Gold Coast’s Jewish community. In 1976, a group of locals established Temple Shalom, a congregation for reformed Judaism, offering the Gold Coast an alternative to Orthodox Judaism. Temple Shalom originated at the Chevron Island home of Leonard and Estelle Spray. As active members of the Hebrew Congregation, they could see that there was a lack of social life and sense of fellowship within the ever-growing demographic of Jewish retirees on the Gold Coast. The Sprays began hosting social functions in their home, pushing all the furniture to the side, making room for as many of their fellow retired Jews as possible to come and enjoy a night or an afternoon playing card games and schmoozing . The social bunch soon began calling for a more religious touch to their gatherings, and the Sprays held a forum where they invited an interstate Rabbi to address the group. By the end of the meeting, they made an historic decision to establish the Gold Coast’s first official liberal Jewish community. Six years later, they built and consecrated their own synagogue on the Isle of Capri. In Australia, no other Jewish congregation has been founded on the basis of supporting the social needs of a retired population.

By 1988, a Jewish cemetery was consecrated at Southport cemetery, together with the establishment of an organisation that takes care of traditional Jewish obsequial rites and observances. Several other Jewish organisations have come and, in some cases, now gone, such as the National Council of Jewish Women, the Jewish Welfare Society, the Jewish National Fund, and Maccabi, a Jewish sporting organisation. A Jewish school was founded in 1994, though it closed its doors in 2008.

Jewish identity and belonging

The Gold Coast remains a place in Australia where religious Jews can have a holiday while maintaining a fully Orthodox lifestyle by means of communal facilities. From humble beginnings in the late 1950s, Jewish communal life on the Gold Coast has encompassed an ever-changing kaleidoscope of people, all of whom have enriched the multicultural life of the city and sustained the Jewish community through an impressive network of charity groups, education facilities, and synagogues.

Perhaps such a time may never come again for the Gold Coast’s Jewish community. Its founding members, including John Goldstein and his family, were a group of leaders dedicated to the betterment and survival of the Jewish people on the Gold Coast. As volunteers, they gave up their evenings for committee meetings and their weekends to take their children to Sunday school. They created a thriving community for European Jews as they recovered from the devastation of the Holocaust. Like other Jewish families on the Gold Coast, John’s parents wanted a better life for their family after the persecution of Jews in Europe. Though travelling far from Europe to a place with no established Jewish communal life, Jewish people took with them their traditions of language, food, charity work, and prayers. Many say that this is the secret to Jewish survival. The Gold Coast Jewish community continues to provide for thousands of transient Jews who holiday in or retire to the area, enabling them opportunities to connect with their Jewish identity.

Sources and further reading

Fabian, A. 1981. ‘From school to “shul”: the early history of the Gold Coast (Queensland) Hebrew congregation.’ Journal of Proceedings (Australian Jewish Historical Society), 9, 2: 97–115.

Goldstein, F. June 2021. Oral history interview, Gold Coast Jewish History project. Interview by Shaina Rother, Gold Coast.

Goldstein, J. June 2021. Oral history interview, Gold Coast Jewish History project. Interview by Shaina Rother, Gold Coast.

Gurevitch, R.N. October 2021. Oral history interview, Gold Coast Jewish History project. Interview by Shaina Rother, Gold Coast.

Kleerekoper, V. 2022. ‘Porush, Israel (1907–1991).’ Obituaries Australia, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, accessed 2022. https://oa.anu.edu.au/obituary/porush-israel-15194/text26970.

Korman, I. September 2021. Oral history interview, Gold Coast Jewish History project. Interview by Shaina Rother, Gold Coast.

Markoe, L. 2004. ‘What is the Mikvah all about?’ The Washington Post, accessed 2022. www.washingtonpost.com/local/what-is-the-mikvah-all-about/2014/11/07/cdff0784-6696-11e4-836c-83bc4f26eb67_story.html

McRobbie, A. 1984. The fabulous Gold Coast. Surfers Paradise: Pan News

Slonim, R. 2022. ‘The Mikveh.’ Chabad, accessed 2022. www.chabad.org/theJewishWoman/article_cdo/aid/1541/je wish/The-Mikvah.html

Samuel, A. September 2021. Oral history interview, Gold Coast Jewish History project. Interview by Shaina Rother, Gold Coast.

Samuel, H. 1966. ‘Fifth annual report of the Gold Coast Hebrew Congregation.’

Related articles