The Brisbane Synagogue

Finding a place for Jewish faith identity in early Brisbane was not a straightforward journey. The story of the Brisbane Synagogue (established 1886) echoes the struggle and success of early Jewish life in the city.

Jennifer Creese and A. Michael Briner

This is a 14 minute read, published June 2024.

In the middle of Brisbane’s central business district sits the local Jewish community’s ancestral gem, its heritage listed 135-year-old synagogue, operated by the Modern Orthodox Brisbane Hebrew Congregation. Now dwarfed on either side by government buildings and high-rise student accommodation, the Byzantine styling of minarets and a massive circular stained-glass window are at once exotic and hidden away from the world around it.

Today’s Jewish residents of Queensland are spread out across the state, from Cairns in the far north down to the Gold Coast in the south. But at the time of the birth of the Queensland colony, it was in the heart of the new capital of Brisbane where its new Jewish settlers would make their place, both socially and physically.

The synagogue is the oldest and most prominent symbol of Queensland’s Jewish community. Yet the story of Jewish life in Queensland does not begin with the building. In many ways, the early Queensland Jewish community’s struggle to find a home for their worship within the city echoes their struggle to find a place for their identity and culture in wider society, and to become part of the vibrant landscape of Queensland’s religious communities as seen today.

Queensland’s first Jews

The first Jewish presence in the Brisbane area predates the synagogue by more than sixty years, back to the arrival of convicts in the Moreton Bay penal colony established in 1824. Home to the most unrepentant criminals and repeat offenders transferred from the larger convict colonies of New South Wales, around one per cent of the Moreton Bay convicts were Jewish, sent there after committing other petty crimes like theft or escape during their initial sentences. In fact, it was a Jewish convict, Lewis Lazarus, who recovered the body of the notorious commandant, Patrick Logan, after he had been killed by Aboriginal warriors in the upper Brisbane River in October 1830, and brought his remains back to the settlement in October 1830 (Wills, 2015, p.136).

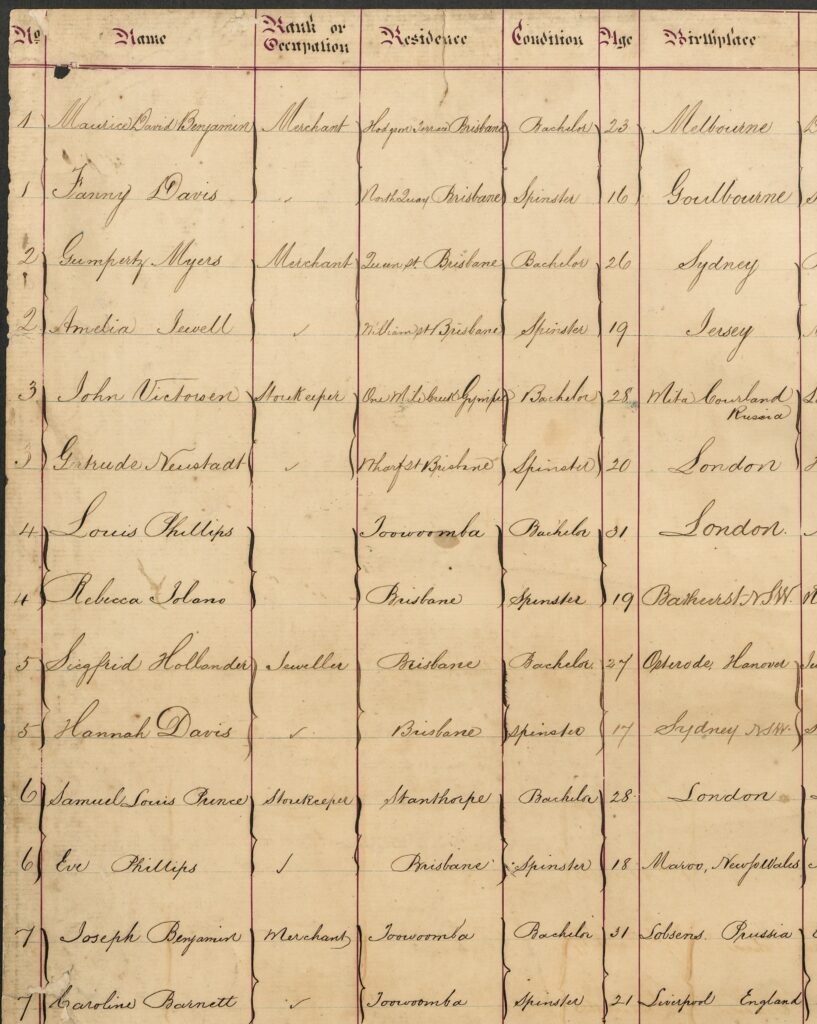

When the penal colony was dissolved and free settlement in the area opened up in 1842, virtually no former convicts remained to settle in the newly developing town of Brisbane. Instead, a handful of Jewish families were among those migrants who came to Brisbane from Sydney, seeking new opportunities with Queensland’s separation from New South Wales in 1859. By the mid-1860s, there was a small concentration of families all living and working closely with each other in central Brisbane. From the initial records of the Brisbane Hebrew Congregation, it appears that these early Brisbane Jews were mostly engaged in trade occupations; men are listed as hawkers, travellers, merchants, and jewellers, but only rarely as professionals.

Most of the new Jewish residents settled in the area of Brisbane around North Quay. The local Jewish residents and families appear to have quickly found each other; it is possible that many knew each other or had shared connections before moving north from Sydney. They began meeting together in each other’s homes, celebrating Shabbat and other important services and running religious education classes for their children together informally. Congregation historian Morris Ochert (1984: 457) identified a ‘Hebrew School at Mr. Jewell’s residence in Tank Street, Brisbane’ in operation around 1864.

As the Brisbane municipality developed and more settlers arrived, this small Jewish community grew. While in 1859 there were barely enough Jewish men to form a minyan for worship, by early 1865 services were so well-attended that private homes no longer could fit in all the worshippers. The Jewish community decided it was time to formalise themselves into a congregation and the search for a new home began.

The first Jewish presence in the Brisbane area predates the synagogue by more than sixty years, back to the arrival of convicts in the Moreton Bay penal colony established in 1824.

A new congregation

A tiny note in the classified advertisements of the Brisbane Courier on March 4, 1865 heralds the beginning of the Brisbane Hebrew Congregation and the first steps in the synagogue’s journey: ‘All members of the Jewish community are requested to attend a meeting, at Mr. B. Benjamin’s, Queen Street, tomorrow, at 11 am, to take into consideration the necessity of forming a Congregation in Brisbane.’ This meeting established a committee of seven to find a place of worship and recruit more members. Two weeks after their first meeting, they passed a motion to formally create a Jewish congregation in the city (Ochert, 1984: 458).

For its first ten years of life, the new Jewish congregation occupied a number of leased rooms in various business buildings around Queen Street each Saturday for services. The first recorded of these is a room in Bulcock’s Building, Queen Street, where a small plaque on the wall now marks the site’s Jewish history. Within months, however, the congregation had moved to larger rooms over the Queen Street store of Mr A. Alexander, one of the Jewish community’s own members. The increasing numbers of storekeepers and importers listed in congregational member records — in addition to ‘businesses attaching and distinctly displaying their Jewish names on their shopfronts and factories, like the Myers & Co glass depot in Queen Street, and Benjamin Brothers in Elizabeth Street’ (Creese 2016a) — indicates the growing wealth and prosperity of the community and of the broader Queensland colony.

The congregation’s leaders approached the Surveyor General of the colony to secure a piece of land for the construction of a synagogue of their own. Unlike many of their Christian neighbours, the Jewish community faced an uphill struggle to build a house of worship. Lacking the wealthy organisational infrastructure and land holdings of the Anglican and Catholic churches, the Brisbane Hebrew Congregation needed to raise the funds itself, mainly from its own members and Jewish philanthropists elsewhere. It is noted in the congregation’s New Synagogue Building Fund Registry that Sir Anthony Musgrave, Governor of Queensland, and the Hon. William Groom MLA were among the non-Jewish contributors.

A site was identified for sale at the corner of Tank Street and George Street, and fundraising began for construction, raising around £200. However the young colony was highly economically volatile in the 1860s, being heavily tied to British banking investments and the agricultural sector. From mid-1866, there weas a rapid economic downturn with many local bankruptcies. This depression, though short, spelled financial disaster for many of the Brisbane Hebrew Congregation’s members, who were forced to return penniless to Sydney. Worse still, the investment of the synagogue building fund was all but wiped out before any progress could be made; the arrangements fell through and the money appears to have been lost. Minutes of a committee meeting in August 1866 recorded a plaintive cry: ‘No building committee is necessary, there being no building funds.’

The search for a synagogue

The Jewish community continued their worship in rented rooms, saving up for the purchase of a Sefer Torah scroll of their own and setting up its own philanthropic society to help fellow Jews who had fallen on hard times in the depression. However, worship out of a rented hall proved difficult, with a lack of secure space for appropriately keeping the Sefer Torah and other important Jewish ritual objects, and obstacles to following the traditions of Orthodox Jewish worship such as separation between men and women in worship.

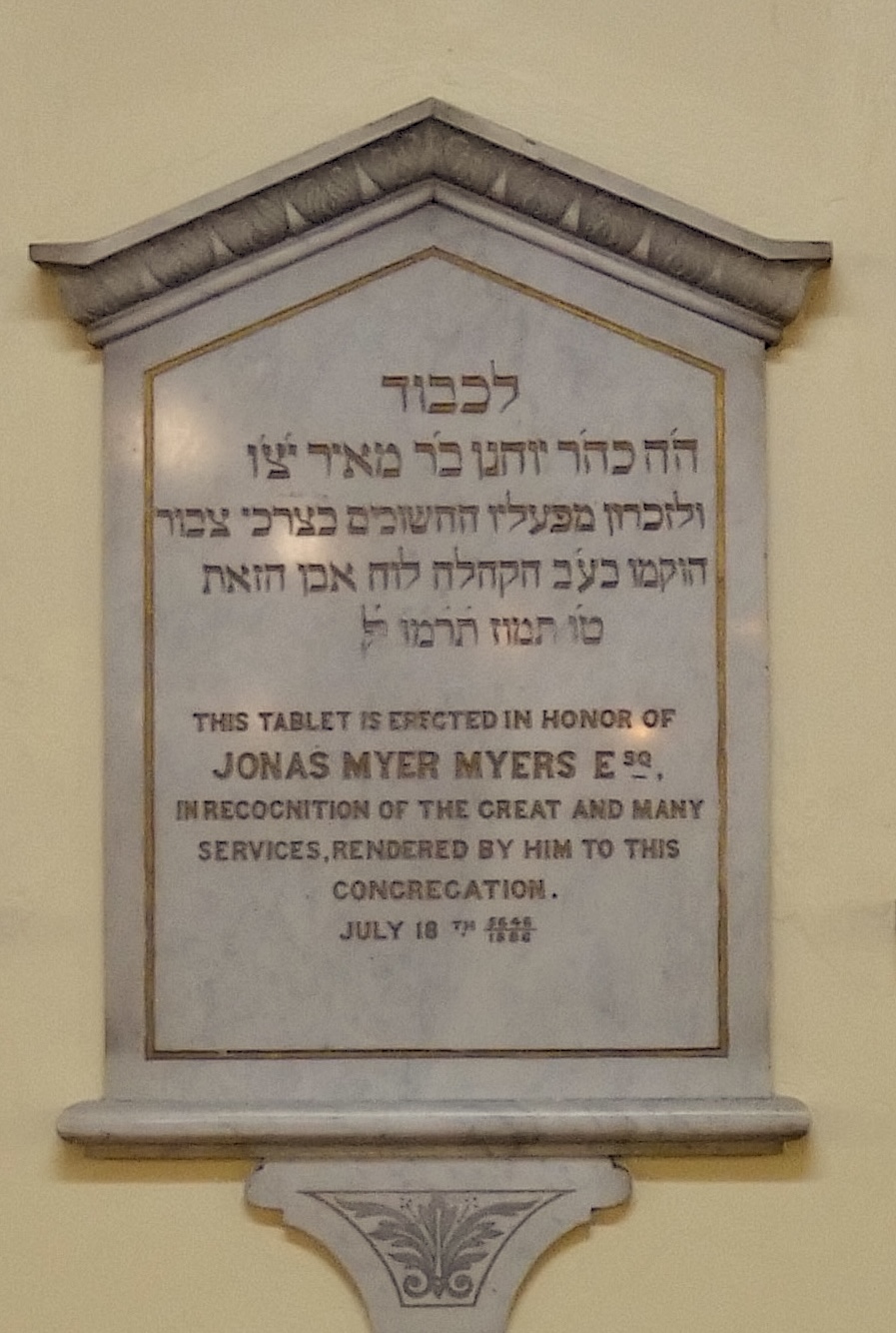

A cottage was leased at the eastern end of George Street in 1867, which served as a synagogue and minister’s residence for the congregation’s religious leader, Rev. Jonas M. Myers. Although he was not an ordained Rabbi, Myers had moved up from Adelaide to serve the congregation in late 1865. ‘He varyingly acted as congregational board President, Treasurer and Secretary, Synagogue Fund trustee, preacher, [Sunday School] teacher, Shochet (kosher butcher), Mohel (performer of ) and dues collector’ (Creese, 2016b: 43), and travelled all over the Queensland colony as far north as Cooktown serving the religious needs of Jewish pioneers.

Myers was not only a tireless congregational worker and religious scholar, but an adept investor. As the economy recovered in the early 1870s, he purchased an empty piece of land in Adelaide Street for £200 out of his own pocket, and sold it at cost and by instalments to the congregation for the construction of a synagogue.

However, the location of this site set off a fierce debate among the congregation, which had now grown substantially and had members who lived across Brisbane. Those community members who lived closer to the centre of town approved of construction at Adelaide Street. But a growing group of community members had settled in the busy commercial district of Fortitude Valley, quite distant from central Brisbane. These community members were reluctant to commit to a long journey by foot or horse-cart every week and wanted a synagogue closer to them. Others, particularly the growing numbers of wealthy businessmen, wanted the synagogue to be constructed on Spring Hill, closer to their grand homes along Wickham Terrace — an impressive synagogue high on the skyline of the city would be a very visible marker of the presence and status of the Jewish community. Myers reluctantly negotiated the sale of the Adelaide Street land to a hotelier named Lennon — the site eventually becoming the Adelaide Street frontage of the landmark Lennon’s Hotel — for £3,000, building up a healthy synagogue building fund despite the lack of a suitable site.

Margaret Street secured

Congregational records indicate that two river-front properties in George Street were considered but rejected. The area had ‘previously housed a burial ground and was both religiously improper and economically undesirable’ (Creese, 2016a). One Jewish community member, local businessman Samuel Davis, constructed a small synagogue hall for the community’s use in the grounds of the expansive home he built at North Quay in 1870, later the first home of the Mater Misericordiae Hospital.

But the Board members of the Brisbane Hebrew Congregation, particularly the building committee, wanted more; they needed to ‘raise a permanent testimony of the existence of Judaism in the city’ (Ochert 1984: 460) with a purpose-built public structure. This public presence was important. Throughout the 1860s and 1870s there was an explosion of religious building in Brisbane, particularly with new churches for Catholic parishes, as part of ‘the civilising role of architecture in the new colony’ (King 2012: 42). To be part of this ‘civilised’ society, the Jewish community would need its own unique architectural presence.

While the search continued, the congregation rented and renovated the ground floor of the Masonic Hall on the corner of Albert Street and Ann Street in 1876, which remained its home until the opening of the new Brisbane Synagogue some ten years later. This move was facilitated by the fact that many of the congregation’s early members and leaders were themselves Freemasons. Most of the early gentlemen’s social clubs of Brisbane directly excluded Jews from membership. Freemasonry, however, ‘with its universal and cosmopolitan outlook provided a unique opportunity for Jews to socialise in a non-Jewish milieu, and by its cultural prestige and societal prominence it was the most important platform for social relations’ (Lanchidi, 2021: 191). Men from the early Brisbane Jewish community rose high in the ranks of the Freemasons, including Adolphus Hertzberg, one-time Brisbane Hebrew Congregation president later elected Grand Master of Queensland in 1909.

One of the congregation’s Board members, Mr R. B. Lewin, at last approached the building committee in 1884 with an offer of a piece of land he had bought on Margaret Street on the edge of the city near the new Parliament House. Like Myers, he had obtained the site during the depression years at a cut price of £200, but rather than sell at a profit, he offered the land at cost to the congregation on the condition that the synagogue would be built there. A title search of the site now occupied by the Synagogue shows there was a dwelling on the site previously; before that, however, it was agricultural land for the convict settlement. There is no mention of the land being sold to Lewin, so presumably he transferred his rights and obligations to the Brisbane Hebrew Congregation before settlement. The new title was issued in the name of Jonas Myer Myers, George Myers, and Lewis Phillips, all leaders of the Congregation’s Board, as joint tenants for the Brisbane Hebrew Congregation, on April 30, 1884 (Russel Hall Architects, 1993: 14).

Also like Myers, Lewin was a staunch community worker and Jewish community pioneer. A former storekeeper in the west Queensland town of Roma, he was well connected among the pioneers of the Darling Downs, particularly the new Jewish settlers. He was instrumental in setting up the now-defunct Toowoomba Jewish congregation and helping them raise funds for the construction of their own synagogue in 1876. The tale of Lewin carrying a Sepher Torah scroll on horseback up the Great Dividing Range from Brisbane to Toowoomba for the founding of the synagogue has been immortalised on a marble plaque dedicated to him in the Brisbane synagogue. Having seen the success of the Toowoomba Jewish community at building their synagogue, he was determined that Brisbane should follow suit.

The synagogue’s construction plans began to pick up pace. A building committee was established; their records, preserved by the State Library of Queensland, document the synagogue’s construction from the committee’s first meeting in July to its final dissolution, task completed, in February 1886. For even with land secured, the synagogue’s journey to construction was anything but smooth.

Designing and constructing the synagogue

The first task was securing an architect and an architectural design. The historical record on this matter is rather complex and ambiguous; various local and architectural historians have weighed in with theories about the design of the synagogue, and the minutes recording the Building Committee’s deliberations and decisions about its design and construction show similar ambiguity and disagreement between committee members. Contemporary newspaper reports, along with the official Queensland Government heritage register for the synagogue, list Arthur Morry, a British engineer and architect and later member of parliament, as the designer of the building and overseer of its construction.

However, several researchers have offered alternative interpretations around the synagogue’s original design, with John East attributing it to Edward Wells Russell, Morry’s brother-in-law, and Morris Ochert and more recently Jennifer Creese and Joyce Arnold identifying prominent Italian church architect Andrea Stombuco as the possible designer. Whichever of these is true, it was indeed Arthur Morry who was welcomed by the Committee in September 1884 as the architect overseeing construction.

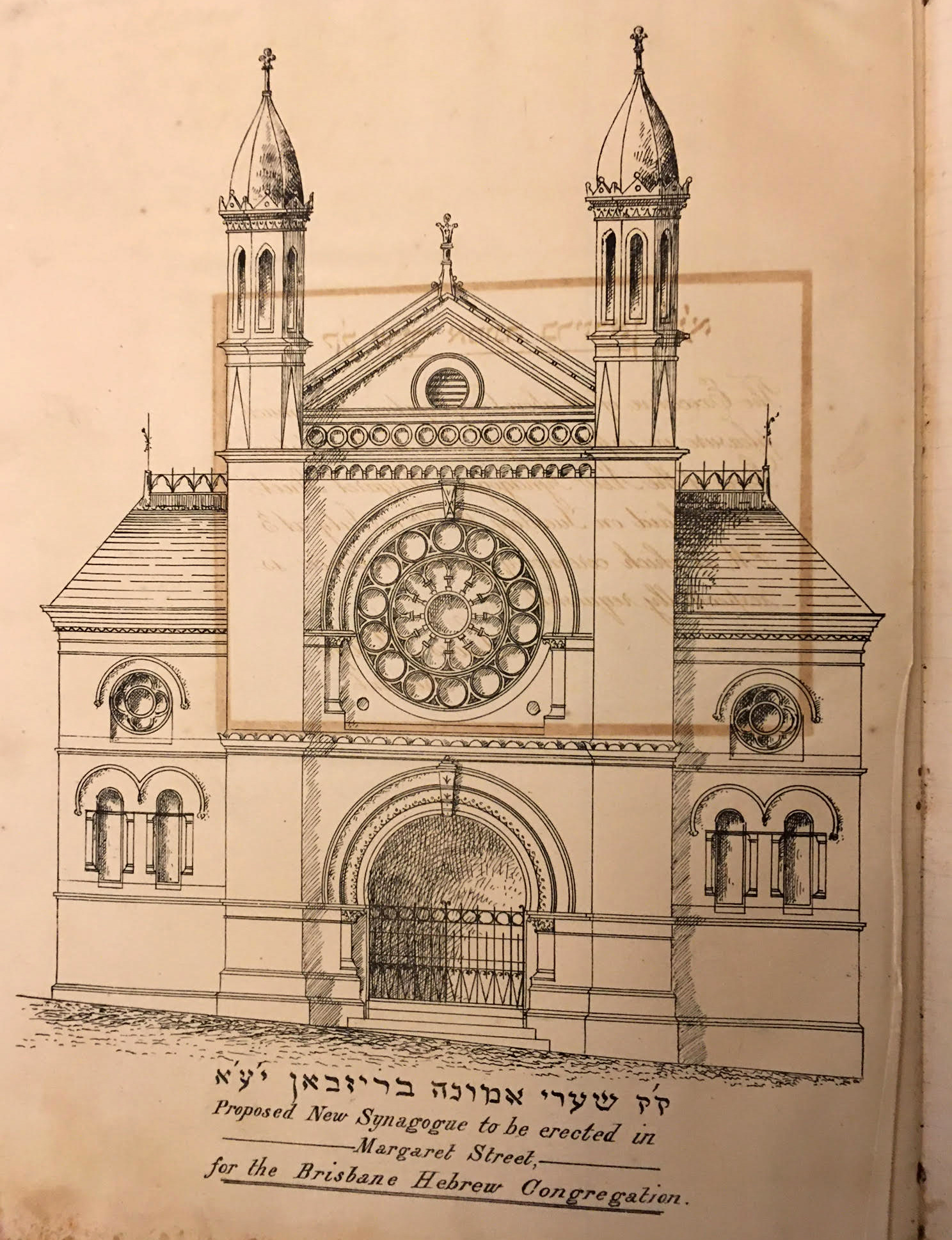

Figure 4: The 1885 sketch of the proposed frontal view of the synagogue, used in fundraising advertisements by the congregation (Brisbane Hebrew Congregation).

Struggles continued, however, particularly financial. The Building Committee had asked for ambitious plans for their new synagogue. Set out in their minutes, requests included a schoolroom, board room, and upper-floor Ladies’ Gallery (as men and women are seated separately in Orthodox Jewish worship), plus seating for six hundred people (revised on completion to seat four hundred: 240 men and 160 women), to a budget of £3,000. Their tight budget might explain their reluctance to work with Stombuco, who ‘was notorious for creating designs that ran far over budget’ (Creese and Arnold, 2021: 167). Morry assured the committee that he could deliver their financial and practical requests, but by January 1885 when the construction tenders were returned, the cost had greatly blown out. The Building Committee’s minutes book documents on January 20, 1885 notes that they sent an irate ‘letter to the Architect stating that as the construction tenders are far above his estimate, we are not now in a position to accept any.’

Meanwhile, community members sought far and wide for building fund donations to meet the expanded costs. Using an image of the synagogue’s planned design, to raise subscriptions they advertised as far away as the Jewish Chronicle newspaper in London, which was circulated to Jewish communities all over the British Empire. The congregation was eventually able to raise £6450 through private donations from local and overseas Jewish donors, including contributions from the Rothschild and Mocatta banking families of London, as well as many non-Jewish donors, which would fully cover the cost of the construction debt free.

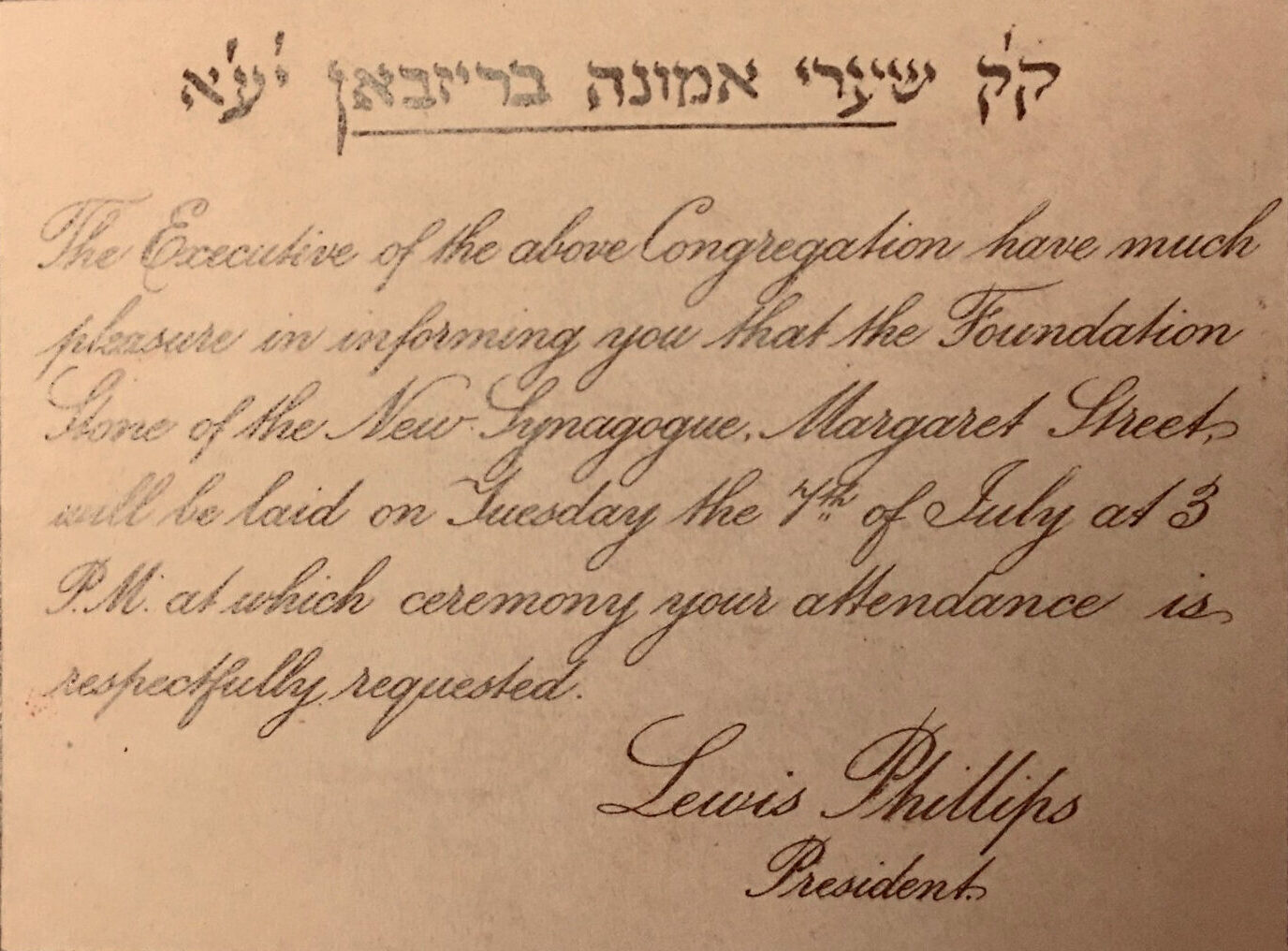

On July 7, 1885, the Building Committee, led by Rev. A. P. Phillips, the congregation’s rabbi, laid the foundation stone for the new synagogue to commence building works, in a grand public ceremony extensively reported in the local press. In a speech which was reproduced in the Brisbane Courier newspaper that day, Phillips spoke about the importance of a permanent synagogue to the Jewish community, not just as ‘a permanent testimonial to the existence of Judaism in this city by setting apart a place wherein the sacred duties of their religion might be performed’ and a ‘powerful aid to spiritual emotion’, but as a sign that ‘Judaism never would die out. It had flourished in this the youngest of the colonies.’

It was an important statement to make for a community made up largely of immigrants who had, a generation earlier, left England and the German states where social and political restrictions had seen many local Jewish communities dry up and die out as their inhabitants headed to the big city ghettoes and emigrated overseas. This was not just a building, then, but a sign of freedom, permanency and belonging.

Figure 5: Invitation sent to dignitaries and the press for the 1885 foundation stone ceremony (Brisbane Hebrew Congregation).

Unveiling a ‘Byzantine’ treasure

After another year of construction, on July 18, 1886, the newly-completed synagogue was finally completed and consecrated to start hosting religious services. As a later historian wrote, ‘Never in the history of Jewry in the State of Queensland was there a more brilliant function than the historic occasion of the opening of the new Synagogue in Margaret Street’ (Bolot, 1925, part 6:2). The grand occasion saw the synagogue full to capacity with members of the Jewish community, a host of public dignitaries and their families including the Chief Justice of the colony, the Attorney General, the Mayor of Brisbane, the Colonial Secretary, and several members of the Queensland Legislative Assembly. Later that week, the Queensland Figaro and Punch magazine reported that ‘there was not a vacant seat upstairs or down, all the leading Christians of Brisbane showing by their presence an interest.’

The interest and support demonstrates that the Jewish community was seen by the city’s elite as ‘a well-established minority with [an] identifiable settlement... [and] success in economic, political and social life’ (Rutland, 2005: 36). More importantly, it demonstrated that the presence of the synagogue, and the Jewish community itself, was endorsed by representatives of the state as a part of Queensland society.

Like many other synagogues of a similar historical period, which served as ‘assertions of cultured, affluent arrival [of Jewish communities] in non-Jewish society’ (Olson, 2019: 205), the Brisbane Synagogue was a spectacular, ornate, and exotic marker of Jewish presence, and a striking addition to the city skyline. The elegant design of the structure itself was referred to in contemporary reports as ‘Byzantine style’ — a term used for public architecture across Europe, including synagogues, which derives from 13th–14th century Islamic design elements such as those seen in the Alhambra in Spain, and which became common in synagogue architecture across Europe in the mid-19th century. However, the synagogue’s design draws on a wide mix of historical architectural styles ‘so eclectic …that they defy simple categorisation’ (Olson 2019: 297). It has many features that point towards Islamic-inspired building traditions, like the pair of minaret-style turrets at the front of the exterior, and octagonal columns with horseshoe-shaped buttresses supporting the Ladies’ Gallery and an Arabic-style almemar in the interior.

At the same time, however, the building also features an ornate gable and large circular tracery windows in the Romanesque style on its exterior (East, 2016: 7), while its interior is laid out in the style of a Gothic cathedral (Creese and Arnold, 2021: 165). In blending these approaches and traditions in their synagogue, the Jewish community captured the story of their quest to find their place as Jews and British Subjects of the growing colony — bringing together different values of “pride in being Jewish, Anglicization, self-help and upward mobility” (Stansky 1995:163) to reflect who they were and aspired to be as part of Queensland’s story.

Figure 7: The interior of the Brisbane Synagogue, as seen from the gallery, c. 2010 (Anna Jacobson).

A community’s living legacy

As years have passed, the Jewish community in Brisbane has changed. A large new group of Russian Jews, culturally distinct from the Anglo-German Jews of the Brisbane Synagogue, arrived in the city in the early twentieth century, and brought new ideas about Jewish identity and belonging to the city. These newcomers spoke Russian, Yiddish, and broken English and, not feeling fully comfortable in the Margaret Street Synagogue, established the South Brisbane Hebrew Congregation, building their own timber synagogue in Deshon Street, Woolloongabba, in 1915.

As war and Nazism loomed in Germany in the 1930s, Jewish refugees — often highly cultured artistic and religious intellectuals — fled to make Brisbane their new home, followed by many more after the Holocaust in the late 1940s. Their experiences had a profound effect on Jewish religion and identity. When Brisbane became the epicentre of the South West Pacific campaign of World War II, hundreds of Jewish servicemen among the thousands of American troops flooded into Queensland and sought out the comfort of Jewish religious practice at the synagogue, in some cases staying on after the war to build new lives locally. New waves of international Jewish migrants from the former Soviet Union, South Africa, Israel, and beyond have also changed the face of the Queensland Jewish community since the Brisbane Synagogue first opened its doors (Briner, 2022).

All the while, the synagogue has changed and grown with the community. In 1906 new school rooms were added; in the 1920s a purpose-built hall with a retractable roof enabling the celebration of the harvest festival of Sukkot ; in 1955 a grand two-story Memorial Hall for social and educational functions; in 1986 elegant stained glass windows commemorating the Holocaust and stories from the Torah; and for 2022 a grand new community facility has been planned (Briner, 2022). Though no longer the epicentre of the Margaret Street scene, the synagogue remains a testament to the early pioneers who dedicated so much to see it to fruition, and to Brisbane’s modern-day Jewish community which ensures it survives and thrives as a living reminder of the place of Judaism — ancient, elegant, subtle yet proud — in Queensland’s religious landscape.

Sources and further reading

Bolot, D. 1925. ‘History of Queensland Jewry.’ Hebrew Standard of Australasia, 8 parts, 27th February 1925-12th June 1925.

Briner, A.M. 2022. Margaret Street Memories: Reflections, Recollections, Reminiscences. Brisbane: Brisbane Hebrew Congregation.

Creese, J. 2016a. ‘A Settlement Geography of Jewish Brisbane.’ Presentation to the Australian Association for Jewish Studies Conference, Brisbane, Australia, 14–15 February. espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:381188

Creese, J. 2016b. Jewish Life in Queensland: Celebrating 150 Years Since 1865. Brisbane: Queensland Jewish Board of Deputies.

Creese, J. and J. Arnold. 2021. ‘The Architectural Provenance of the Margaret Street Synagogue, Brisbane.’ Australian Journal of Jewish Studies XXXIV: 157–87.

East, J. W. 2016. ‘A checklist of Romanesque-inspired architecture in Australia. Part 3: Queensland.’ Unpublished manuscript, accessed 12 May 2022. espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:395203.

King, S. 2012. ‘Eclecticism in the Work of Queensland Colonial Architect F.D. G. Stanley, 1871–1881.’ Fabrications 21, 2: 37–60.

Lanchidi, P. 2021. ‘A Kabbalistic Lithograph in Australia: Rabbi A. B. Davis’s Lectures on the Origin of the Rites and Worship of the Hebrews.’ Australian Journal of Jewish Studies XXXIV: 188–223.

Ochert, M.S. 1984. ‘History of the Brisbane Hebrew Congregation, part one.’ Australian Jewish Historical Society Journal 9, 6: 457–65.

Olson, J. 2019. ‘Reimagining the Synagogue in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries’. In S. Fine (ed.) Jewish Religious Architecture: From Biblical Israel to Modern Judaism. Leiden: Brill, 287–306.

Russell Hall Architects. 1993. ‘Hebrew Synagogue: conservation study and policy.’ Hill End: Russell Hall Architects.

Rutland, S. D. 2005. The Jews in Australia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stansky, P. 1995. ‘Anglo-Jew or English/British? Some Dilemmas of Anglo-Jewish History.’ Jewish Social Studies 2, 1: 159–78.

Wills, R. 2015. Alias Blind Larry: The Mostly True Memoir of James Laurence the Singing Convict. Melbourne: Australian Scholarly Publishing.

Related articles